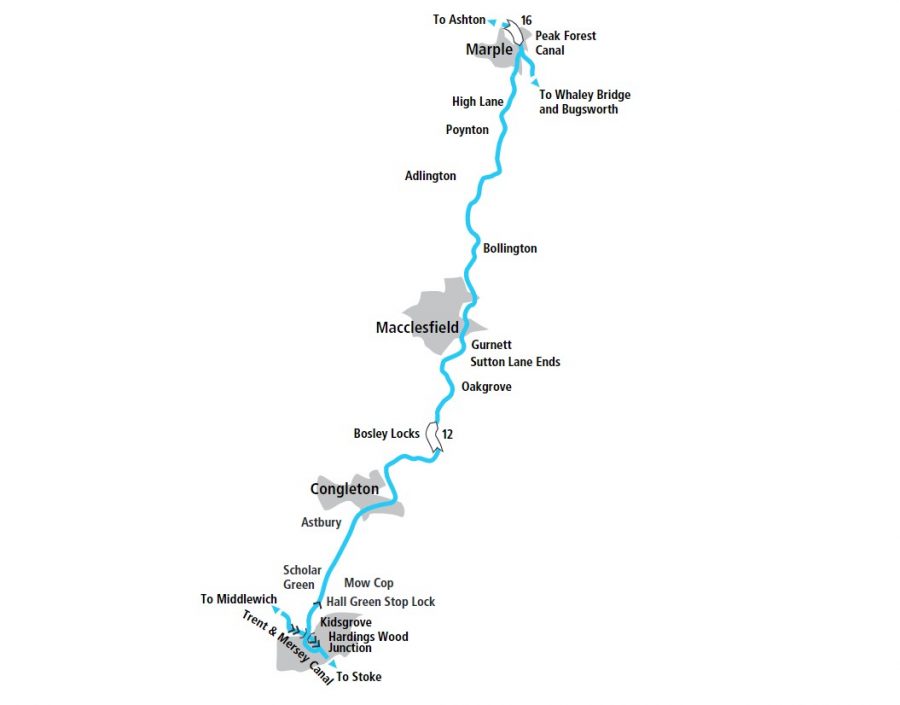

We follow the ‘Macc’ southwards through old mill towns, with the Peak District hills rising on one side and broad views across the Cheshire Plain on the other side

Fancy stopping for a drink? See our top ten pubs on the Macclesfield Canal

At a junction just above the top of the Marple Locks flight on the Peak Forest Canal, the Macclesfield Canal branches off southwards under a characteristic stone-built towpath bridge and through the remains of an old stop- lock. This used to keep the two canal companies’ water supplies separate, but lost its purpose and its gates long ago as the canals came under the same ownership, so now you cruise straight through.

And that junction immediately introduces one of the most well-known features of the ‘Macc’. Well, perhaps two, actually. Firstly there’s the sheer quality of the masonry of the original stone bridges found all of the way along the canal, but the ‘roving bridges’ or ‘turnover bridges’ taking the towpath from one side to the other are particularly splendid examples of this work. Built to the traditional design, with the towpath passing under the bridge and then twisting around to cross over it, so that the towrope on horse-boats didn’t need to be detached when the towpath changed sides of the canal, the ones on the Macclesfield have such a fine sweeping curve to the towpath walls that they have earned the nickname ‘snake bridges’ for the way that they snake around.

Marple wharf with ‘snake’ bridge in the background

After a mere 50 yards or so, the towpath crosses back from the left to the right in a second of these bridges. Why? Because there was a wharf on this section, and it would make sense to run the towpath on the opposite side of the canal from the wharf, to keep towropes and horses away from boats moored up to load or unload (and light-fingered passers-by away from any cargo). Once past the wharf, the towpath could resume its usual position on the downhill side of the canal.

Impressive former mill building in Marple

The wharf isn’t the only reminder of the industrial origins of this largely rural route: an impressive mill building stands on the east bank as the canal leaves Marple for open countryside, meandering gently as it heads towards High Lane.

It may not be immediately obvious, given its similarly slightly winding route and old stone hump-backed bridges, but this canal dates from a later era than the Peak Forest, opened for rebuilding of bridges – several of which are now flat-decked structures rather than the original stone arches.

An old railway – now the Middlewood Way trail – parallels the canal as it continues southwards to Bollington, site of one of the most impressive structures on the canal. A mighty embankment crosses the valley, and was the cause of some headaches for the canal’s builders. It was originally planned with much gentler slopes; however the engineers felt that its largely stone-filled construction would allow it to be built with banks as steep as a 45 degree slope – with a consequent saving of land and materials – but with the option to revert to the original design if there were problems. There was indeed a serious slip, but having left it for a period to settle, the builders had a second attempt to complete it, and it’s stayed up ever since.

An equally impressive mill stands by the canal near the north end of the embankment, and another to the south, reminding us of Bollington’s history as a centre for cotton spinning – although the buildings now house modern light industries and apartments, following the demise of the local textile industries around 1970. Another aqueduct crosses Grimshaw Lane, close to the site of the 1912 ‘Bollington Burst’, a disastrous breach in the canal embankment which is reported to have emptied the entire canal from Bosley Locks to Whaley Bridge, caused flooding in Bollington, and extinguished the furnaces in the gasworks. 100 men were taken on, 160 boatloads of material brought in, and the breach was repaired in three weeks.

The massive Adelphi Mill in Bollington

Passing through Bollington

Three more miles of countryside bring us to Macclesfield, where the canal passes through on the hillside high above the town centre.

Approaching Macclesfield

Macclesfield was famous as a silk town, and there is still a little produced as well as a mill preserved as a museum; however the prominent mill building standing by the town alongside a boatyard and moorings (handy for the half-mile walk to the shops) is actually the Hovis mill. In fact the flour for the well- known brown bread was only ground here for six years from 1898 to 1904 before its success outgrew the premises; the building subsequently made the wrappers for the loaves, before it was converted into to residential use in the 1990s.

The mill that once ground flour to make Hovis bread

The canal leaves Macclesfield through a dramatic steep-sided cutting, its higher eastern side supported by numerous massive stone buttresses added over the years to prop it up (and still the occasional need for more work, as an unscheduled stoppage a few years ago testifies). Another high embankment and aqueduct over a road at Gurnett marks a rather curious coincidence: famous early canal engineer James Brindley served his apprenticeship as a millwright from 1733 to 1740. But it would be another two decades before his involvement in canals began; another 12 years and he was dead. How odd, then, that almost 60 years later in 1831 a canal embankment should be built right past where he had spent his formative years.

The canal leaves Macclesfield via a dramatic steep-sided cutting

The hills recede for a little while as the canal crosses open countryside before another Macclesfield Canal characteristic feature is introduced. Or perhaps I should say “former feature”: until the 1970s hand-operated swingbridges were a frequent sight on the canal, but over the years they’ve been gradually removed until only a couple remain, and only this one hand-operated. A mile further on is the power-operated Royal Oak bridge, carrying a minor road.

The last survivor of a the once common manually operated Macclesfield Canal swingbridges

We haven’t made any mention of locks so far. Another sign that this was a later canal benefiting from some decades of engineering development since Brindley’s day is that all of the canal’s locks were grouped together in one place for efficiency of operation, and we’re now approaching that Bosley flight of 12 locks. They’re in a really attractive setting overlooked by the hill known locally as The Cloud (and with a distinctive ‘notch’ out of the end of it, that being the quarry which provided the stone for the locks, and later for the nearby railway viaduct), and with a few unusual features. Firstly (and unlike most narrow locks) they have paired gates not only at the bottom end but at the top too, where a single gate is the norm elsewhere. Secondly they’re fitted with water- saving sideponds, although they’ve been out of use for many years (one has been restored as a heritage feature); thirdly there were wooden platforms alongside the lock tails to enable the crew to get on or of a boat – and some remains survive.

The flight of 12 Bosley Locks are set in fine rural surroundings

Below the 11th lock the canal takes a sharp right turn, and passes under an old railway bridge which carried the former Macclesfield to Leek line before descending the final lock – but if you look carefully you might spot traces on the eastern side of the canal of another former railway: a horse-tramway linked a canal wharf below the lock to a nearby corn mill.

The locks have carried the canal down into the River Dane’s valley, and it crosses the river on a sizeable single-arch stone aqueduct before heading west, then turning south, and finally west again as it negotiates the hilly terrain to reach Congleton, with a high embankment and a long cutting leading into the town. Or not quite into the town, actually: as with Macclesfield, the engineering and water supply considerations for the canal’s builders meant that it passes some distance from the town centre, and at a rather higher level. Congleton Station, where canal, railway and road make a three-level crossing, or Dog Lane Aqueduct (a spitting image of Nantwich Aqueduct on the Shropshire Union – both by Thomas Telford) half a mile further south are both good places to moor up and walk into town.

Dog Lane Aqueduct in Congleton, designed by Thomas Telford in the same style as his Nantwich Aqueduct on the Shropshire Union Canal

Congleton is another former textile mill town, with silk, velvet and fustian among the fabrics once produced; today it has useful shops, plenty of pubs, and a local nickname of ‘Bear Town’ (as a result of the legendary events of 400 years ago when the money raised for a new town Bible were instead spent on a replacement bear-baiting bear just before carnival time).

The canal’s major engineering features have now been left behind (apart from a minor road aqueduct so small and well-concealed that you won’t even spot it from the canal). However it continues to run along the side of the hills, with Congleton Edge and Mow Cop (complete with folly ‘castle’ on the top) to the left, and views stretching right across the Cheshire Plain to the Welsh hills on the right. Passing Scholar Green village, the canal reaches the curious Hall Green Stop Lock: just as the canal began with an old stop lock, so it ends with one where it meets the Trent & Mersey Canal. But unlike the long-abolished stop-lock at Marple, this one still lowers the canal some six inches or so. And that’s not its only oddity: you can see from the extended lock chamber that it used to actually be two locks end-to-end, one operated by each canal company, allowing for the water level in the Macc to be either higher or lower than in the T&M. And the final quirk is that it has two gates at the top end, but only one at the bottom – a reversal of the more common practice.

The unusual Hall Green stop lock: shallow and, with twin gates at the top but only a single one at the bottom

Although it’s technically the end of the Macclesfield Canal, we haven’t quite reached the Trent & Mersey Main Line yet. There’s another mile and a half of canal, but it was built by the T&M company as a branch of their canal – and it follows their house style of brick bridges rather than the stone of the Macclesfield company.

Approaching Pool Lock Aqueduct over the Trent & Mersey Canal

It ends with another oddity: rather than directly joining the Trent & Mersey, it crosses over it on the Pool Lock Aqueduct, turns sharp left, and the two canals run parallel for half a mile, before the T&M rises through two locks, the Macc makes another left turn, and the canals meet at Hardings Wood Junction, in the town of Kidsgrove.

So (rather unexpectedly) you take a left turn to stay on the Cheshire Ring, or go right for Harecastle Tunnel, the Midlands and the South.