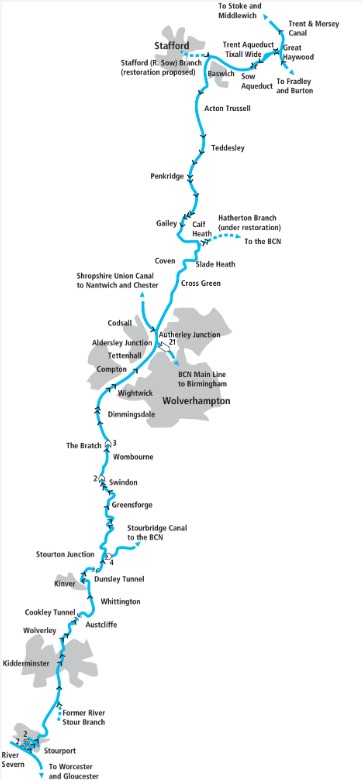

From Great Haywood the Staffordshire & Worcestershire Canal meanders through attractive Midlands scenery before following the Stour valley down to the Severn at Stourport

The splendid brick arch bridge which carries the Trent & Mersey Canal’s towpath over the very start of the Staffordshire & Worcestershire Canal at Great Haywood Junction is a classic piece of 18th century waterways design. It’s attractive but also entirely functional, its brick parapets sloping right down to the ground at each end, ensuring that the boat horses’ tow-ropes wouldn’t snag as they crossed the bridge.

Fine towpath bridge spanning Great Haywood Junction

Part of Brindley’s grand design

It was also a key location in the early waterways network of the late 18th Century, forming a crucial part of famous canal engineer James Brindley’s ‘Grand Cross’ masterplan for linking four great rivers to the Midlands. The irregular V-shaped route of the Trent & Mersey formed two of the arms of this cross, reaching north westwards to the Mersey (via the Bridgewater Canal), and north eastwards to the Trent. Here at Great Haywood it met the Staffs & Worcs, which formed the south western arm linking to the River Severn at Stourport. And finally a few miles east of here at Fradley Junction was the start of the south eastern arm of the Cross, a connection via the Coventry and Oxford canals to the Thames.

To further add to its importance, near its mid-point at Aldersley Junction the Staffs & Worcs was joined by the Birmingham Canal, forerunner of today’s much-rebuilt Birmingham Canal Navigations Main Line. This provided the Staffs & Worcs Canal with much of its trade from the developing industries of Birmingham and the Black Country.

Today it’s one of the most popular leisure cruising routes, thanks to its stunning scenery, its canal heritage and its position at the heart of the network, forming part of several attractive cruising circuits. But for a time in the mid 20th century it was in danger of closing. Competition from other, more direct canals such as the Worcester & Birmingham and the Shropshire Union as well as newer modes of transport in the form of railways and roads had left it with little trade. So much so that when waterways revival pioneer Tom Rolt came this way on his famous 1939 journey on his narrowboat Cressy, he reported that this northernmost length for the first four miles from Haywood was completely unused, the channel weeded-up, the locksides overgrown and the paddle gear stiff from lack of use.

By 1949 the only freight carried on the entire canal was on a one-mile section between Autherley and Aldersley junctions. A decade later it was proposed for closure, but the arrival of leisure traffic and some active campaigning by the Staffs & Worcs Canal Society saved it.

Aqueducts and the ‘wide’

It’s a far cry from that situation today, with a boatyard and basin right by the junction, moorings along the start of the Staffs & Worcs, and plenty of passing craft as it begins its journey with an aqueduct over the River Trent. It’s a typical James Brindley aqueduct from the early years of canal construction: heavily built in stone on a series low arches rather than the lightweight cast iron structures of later eras. And the canal’s route is similarly characteristic of Brindley’s work. It meanders gently as it follows the contours to keep earthworks (and therefore cost) to a minimum, but without the exaggerated windings of some canals completed by Brindley’s successors who seem to have taken this technique to extremes. Incidentally, this is one of the few canals that he saw completed: it opened in May 1772; he died in September.

Moored on the curious large expanse of water known as Tixall Wide

One feature that isn’t characteristic of Brindley, the Staffs & Worcs, or indeed of any other canal is Tixall Wide, a remarkable wide expanse of water that the canal passes through. It appears to have been created to appease the owner of Tixall House, who preferred a view from his land that looked more like a lake than the canal. The house is long gone, but the three-storey (plus turrets) gatehouse is impressive enough, and is now a Landmark holiday let. Be wary of straying to the edges of the Wide, as it’s shallow in places.

The first lock, Tixall Lock, begins the gentle climb towards the canal’s summit. Like most canals in the Midlands, the S&W was a narrow canal, so it’s built to take narrowboats of around 72ft by 7ft. Another Brindley style aqueduct crosses the River Sow, as the canal follows its valley west towards Stafford.

Passing the entrance to the former River Sow or Stafford branch of the canal (see our feature about the canal’s branches), the canal turns south westwards, missing Stafford town centre by a mile or so – the nearest access to the town is from Bridge 98.

Tree-lined length near Baswich

Climbing to the summit

Locks continue the gentle climb as the canal rubs alongside the little River Penk through what would have been quiet, gentle Midland countryside until the 1960s arrival of the M6 motorway which disturbs the peace for a few miles. To the east, the ground rises towards Cannock Chase, with 26 square miles of heath and woodland within a few miles of the canal. Penkridge, a large village close to the canal, is a handy place to stop for shops and pubs.

Reaching the canal’s summit at Gailey Lock, with its distinctive roundhouse

Five locks spread out over a couple of miles end at Gailey Lock, accompanied by its distinctive circular lock house, where the canal reaches its summit level at around 340ft above sea level. A winding length, as the canal sticks to this contour, leads via Hatherton Junction (where the Hatherton Branch used to lead eastwards towards Cannock) to Coven, with a handy waterside pub.

Skirting the Black Country

The canal is approaching the outskirts of Wolverhampton, but for much of the way it manages to distance itself from the warehousing and residential estates, partly thanks to a long, narrow and rocky cutting (so narrow that passing places were built to allow boats to pass each other) that enables it to maintain its level through higher ground. On emerging from the cutting, a towpath bridge on the right marks the start of the Shropshire Union Canal at Autherley Junction. Barely half a mile further on at Aldersley Junction, the main line of the Birmingham Canal Navigations branches off on the left, climbing a long flight of locks leading upwards into Wolverhampton.

In fact the closeness of these two junctions led to some shenanigans between canal companies. Following the opening of the Shropshire Union route in the 1830s, much of the busy long distance trade between the Birmingham Canal Navigations and the North West, which for the previous 70 years had travelled via the Staffs & Worcs and the Trent & Mersey, switched to using the ‘Shroppie’ instead. Understandably miffed at seeing their trade disappear, the Staffs & Worcs company responded by imposing extremely high tolls for the remaining half mile of their canal (between the two junctions) that the boats still had to use to get from the BCN to the ‘Shroppie’. These two companies, equally unhappy at what they saw as being held to ransom by the Staffs & Worcs, planned a short new direct link between their canals, bypassing the S&W by crossing over it on an aqueduct. They got as far as submitting parliamentary bill for the link before the Staffs & Worcs backed down and reduced the tolls.

The descent begins

Continuing south west from Aldersley, the canal maintains its semi-rural appearance through Wolverhampton’s suburbs as it follows a wooded cutting between sports grounds and a racecourse. At Compton Lock the summit level comes to an end, and the descent towards the River Severn begins – gently at first, as the built-up area is left behind and the canal meanders through countryside past Dimmingsdale and Awbridge.

Descending the remarkable Bratch not-quite-staircase locks

Approaching Wombourne the descent steepens as the canal reaches the remarkable Bratch Locks. This closely-spaced set of three locks might look at first appearance like a staircase, with each chamber leading directly into the next one, but closer examination reveals that they are in fact separate locks, each one with its own top and bottom gates – albeit the bottom gates of one lock are just a few feet from the top gates of the next. This isn’t just a quirky feature; it’s fundamental to the operation of the flight. These short pounds are linked via culverts to side-ponds on the far side of the towpath, which act as small reservoirs to increase the effective size of the pounds. This means that the flight is operated like normal non-staircase locks. (But don’t worry – there’s usually a keeper available to help). Small stone and metal staircases provide access to the locksides, and the whole structure is topped off with another unusual lock house – this one is octagonal rather than circular.

A mile two further on, you’ll appreciate the difference when you reach Botterham Locks – which actually do form a genuine staircase, with the top lock opening directly into the bottom one. So as usual with staircases (and unlike Bratch) you’ll need to remember not to try to empty a lock into one that’s already full, or fill a lock from one that’s already empty.

Botterham Locks, which (unlike Bratch) do actually form a staircase

Into the Stour Valley

The canal is now entering one of its most attractive lengths, as it gradually descends into a deepening wooded valley with outcrops of red sandstone. In the three miles of secluded water from Greensforge to Stourton, only one very minor road crosses the canal. Look out for the aqueduct (and the sharp bend immediately after it!) where the canal crosses the River Stour, which it follows for the rest of its route, and the ‘Devil’s Den’ – a former boathouse carved out of the rock.

In a characteristic sandstone cutting near Greensforge

At Stourton Junction the Stourbridge Canal branches off on the left, climbing through four locks on the start of its journey to meet the Dudley Canal and provide another route into the Black Country. Just beyond is the unlikely-named Stewponey Lock, named after a former nearby pub. This in turn is claimed (by none other than Rev. Sabine Baring Gould, author, collector of folk songs and writer of Onward Christian Soldiers) to have been a a corruption of the Spanish place-name Estepona, that being where the landlord had met his Spanish wife while on military service.

Returning to quiet countryside again, the canal reaches its first tunnel: although at a mere 25 yards it seems barely long enough to merit that description, it was clearly hewn through the sandstone and left largely unlined.

Cookley Tunnel passes right under the village

Kinver is an interesting village, notable for its remarkably recent cave dwellings and for a number of pubs. The canal’s journey down the wooded valley continues with another slightly longer tunnel passing dramatically directly under the outcrop carrying Cookley village, and for the curious cavern (perhaps a lock keeper’s store or boat horse stable?) hollowed-out alongside Debdale Lock. The contorted turns of the canal as it keeps to the narrow valley make for some interesting steering for those in full-length craft.

Kidderminster, carpet town

Finally as the canal approaches Kidderminster the valley begins to broaden out, and Kidderminster Lock stands is overlooked by the parish church in the town centre. The lock exits through a tunnel-like bridge under a main road junction into what used to be a canyon-like length hemmed in by tall industrial buildings, the carpet mills for which the town was famous. Today many have gone, and others have found new uses, but some carpet making continues and there is a museum of the industry.

Kidderminster Lock, overlooked by the parish church

Another of the town’s attractions is the Severn Valley Railway (see inset), whose steam trains can be seen crossing the canal on a high viaduct as the canal leaves the town.

The steam railway is heading for its first stop at Bewdley on the banks of the River Severn, and there is an often-repeated story that the original plan was for the canal to also meet the river at Bewdley – but that the citizens of Bewdley were having none of this, and told James Brindley to “take his stinking ditch elsewhere”. He did so, and took it to a tiny riverside hamlet called Lower Mitton, which (thanks to the trade that the canal brought) soon grew into the prosperous town of Stourport, while Bewdley was left to rue its remarks as its fortunes declined, bypassed by trade. It’s a great story, but it probably isn’t true: the local geography meant (as evidenced by the viaduct and a tunnel on the railway line) that a route to Bewdley was always going to be much harder to build (especially to an early engineer seeking to avoid heavy engineering works) than simply continuing down the Stour valley to end where the Stour meets the Severn.

Overhanging red sandstone outcrop at Falling Sands Lock

Not that this was an entirely trouble-free route, as the name of the last lock before Stourport suggests: Falling Sands Lock sounds like a name to strike fear into the heart of a canal-building contractor.

Stourport, canal town

A final winding length leads into the town, where the deep York Street Lock takes the canal into the upper basin. This is the start of a complex of no fewer than five canal basins, linked together by connecting arms, and by both broad and narrow locks to the River Severn.

Part of the complex of five basins at the canal town of Stourport

Normally the broad locks are only used by wide-beam craft from the river which are using the basins for mooring. For narrow-beam craft arriving from the canal, the usual route through is to turn right at the first basin, then left into the first of two pairs of narrow-beam staircase locks, then straight on into the second pair, which leads into the river.

But don’t just head through the basins and on down the Severn: stop for a while to visit what’s probably the country’s best example of a canal town, built around the canal basins, and (irrespective of whether the “stinking ditch” story is true) a town which owes its existence and its prosperity to this fascinating waterway.