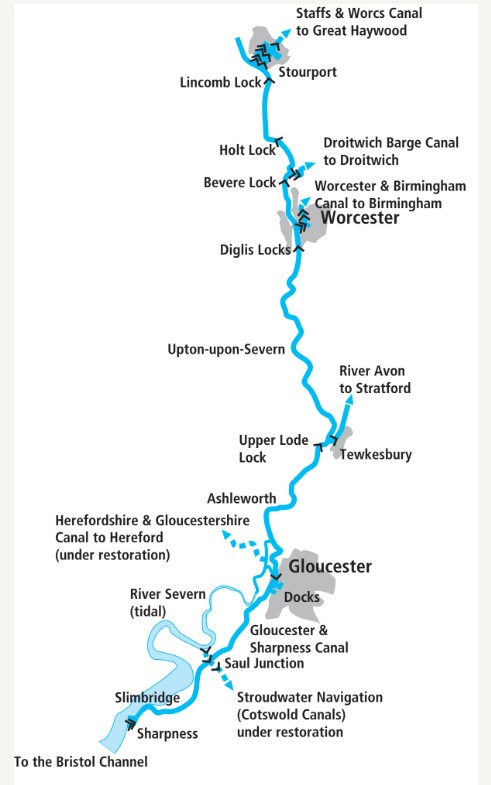

A guide to navigating the quiet, often wooded River Severn by narrowboat, travelling downstream from Stourport to Gloucester. See also our guide to Canal Boat’s choice of ten top pubs on the River Severn and Gloucester & Sharpness Canal here

There’s a world of difference between the River Severn and the last river-based waterway we covered – the Calder & Hebble Navigation. Whereas the Calder was very much a ‘river navigation’ – a waterway created by building locks and artificial cuts, interspersed with lengths of river – the Severn is much more of a ‘navigable river’, with almost all of the navigable 43 miles from Stourport to Gloucester following the natural river, and locks generally few and far between.

There’s a world of difference between the River Severn and the last river-based waterway we covered – the Calder & Hebble Navigation. Whereas the Calder was very much a ‘river navigation’ – a waterway created by building locks and artificial cuts, interspersed with lengths of river – the Severn is much more of a ‘navigable river’, with almost all of the navigable 43 miles from Stourport to Gloucester following the natural river, and locks generally few and far between.

Until the 1840s even those few locks had yet to be built, and boats arriving on the river from the Staffordshire & Worcestershire Canal at Stourport, where we begin our journey, would have had a lock-free clear run down the river, all the way through to the tidal estuary.

That’s when there was enough water for them: for two months of a typical summer, navigation from Worcester up to Stourport on the unimproved river wasn’t possible at all.

On the other hand, when there was adequate water in the river, it was navigable for a long way above Stourport – all the way through Bewdley and Ironbridge to Shrewsbury, and at times of high water onward right up to Pool Quay, the wharf for Welshpool. On the way there it provided the opportunity to interchange cargoes with the Montgomery Canal in Welshpool, the Shewsbury Canal in Shrewsbury, and the Shropshire tub-boat canal system at Coalport – although it was never physically connected to any of these.

I referred above to the ‘navigable 43 miles’ from Stourport to Gloucester, but in theory the river is still legally navigable all the way up to Welshpool; however silting and changes to the river gradually saw these lengths fall out of use and become to shallow for all but small craft in most conditions, with the last few barges making it through to a few miles above Bewdley in the early 20th century.

Several proposals over the past 50 years to create locks and weirs to make the upper river fully navigable have come up against opposition and made no practical progress. So today the limit of jurisdiction of the Canal & River Trust – and of any responsibility to maintain the river for navigation – is where the Gladder Brook enters the river about three quarters of a mile above Stourport, although small craft use the reaches above (plus trip-boats and local boating in Shrewsbury). If you want to try your luck above that point, you’re on your own – and bear in mind that a shoal a little way below Bewdley usually prevents any but the shallowest craft from reaching the town.

Stourport Bridge, with the town and canal basins off to the right

Most boaters will instead turn left as they exit the lower staircase locks leading into the river from the complex of basins, locks and historic buildings which make Stourport one of our great ‘canal towns’, and head downstream on the Severn.

One thing that the Severn does have in common with Yorkshire’s Calder & Hebble Navigation is that they both carried freight regularly until relatively recently – right up to the 1990s in the case of the Severn, although only on the lower reaches – and you’ll see signs on your left of former freight wharves as you leave Stourport behind. However most of the river is rural, often wooded with steep banks and outcrops of sandstone, and quiet.

Passing signs of former freight wharves on the edge of Stourport

Not much over a mile from Stourport is the first of those locks built on the river in the 1840s, Lincombe Lock. In keeping with the mid-1800s move to steamers and other larger craft on the bigger rivers, its generously-sized chamber takes boats up to some 90ft by 20ft – but note that the 20ft width is insufficient for three narrowboats side-by-side, so don’t try! As with all the locks on the river, it’s keeper-operated, and unlike some of our larger rivers (such as the Thames) there’s no facility for boater-operation out-of-hours.

Attractive moorings on the upper reaches above Holt

Another wooded reach leads downstream to Holt, where there’s another lock, followed by Holt Fleet Bridge. This is of interest for two reasons – firstly as an 1828 cast iron structure built by famous engineer Thomas Telford; and secondly because it’s the first bridge we’ve passed under in the six miles since joining the river in Stourport. But despite this apparent lack of contact with the outside world, one thing the Severn doesn’t lack is waterside pubs, with four so far.

The next link to the canal system arrives at Hawford, with the restored Droitwich Canal entering from the left as the river makes a right hand bend. If you’re turning off onto the canal, the angle of the junction means you’ll need to swing it wide to approach the landing stage and the canal’s first lock.

Leaving Bevere Lock, keeper-operated like all the Severn locks

Bevere Lock (followed by yet another riverside hostelry) keeps up the interest, then the river gradually begins to enter the outskirts of Worcester. The city’s racecourse on the left, houses on the right, and a veritable flurry of bridges by Severn standards (a footbridge, a railway viaduct and the main road bridge) announce our arrival in the cathedral city. Moor up at visitor moorings near the railway bridge to visit the town, its attractions and shops.

Look out for the cathedral tower ahead and to the left, and also the large numbers of swans on the river as you pass under the main road bridge. The next canal connection is just a few hundred yards downstream, where another sharp left turn (with landing stage) gives access to the entrance lock of the Worcester & Birmingham Canal. The first two broad locks lead up to Diglis Basin Marina, with useful boaters’ facilities.

Worcester’s town bridge and riverside, home to many swans

Back on the river, a basin on the left is another reminder of the former heavy barge traffic – 400-tonne tankers delivered oil and petrol here until the 1970s. The paired Diglis Locks follow, the larger right-hand chamber (around 140ft by 30ft – allowing larger tankers) being the one normally used. Not that you’re likely to see any boats that size on the river today, given the (near) demise of freight – but there are some sizeable passenger boats on the river. Sadly the largest of them is no more – the Oliver Cromwell, a former Dutch barge converted to a floating hotel in the style of a Mississippi stern-wheeler, left the Severn for a new home in Ireland in 2018, but sank while under tow in the Irish Sea.

Approaching the paired Diglis Locks below Worcester

A straight reach heading south from Worcester leads to a more winding length passing Kempsey and Severn Stoke (but with few if any places to moor) and another long gap between bridges until Upton-upon-Severn. Look out on your left near Upton for Ryall Wharf, where you may well see a loaded barge. Up to now I’ve referred to freight traffic in the past tense, but in 2005 a new short-distance trade began, carrying gravel from a quarry at Ryall to a gravel washing plant a couple of miles downstream at Ripple, to keep the traffic off the local roads.

Upton is a fine riverside town with historic buildings including several pubs and restaurants facing the riverside, and visitor moorings upstream of the bridge.

Upton-upon-Severn has an attractive riverside with several pubs

Continuing southwards between rather less steeply-sided banks, the river passes under Mythe Bridge (another Thomas Telford structure in cast iron) as it approaches Tewkesbury – but it doesn’t quite reach the town. Instead, boaters reach the town via its tributary the Warwickshire Avon, which joins the Severn here.

The Avon is run by the Avon Navigation Trust, so those wishing to continue through the town towards Evesham and Stratford will need to buy an Avon licence; however those simply wanting to visit the town may moor overnight on the landing stage downstream of the lock (on payment of a mooring fee). Incidentally the old flour mill building near the landing stage was the destination of the final regular traffic (until the gravel trade mentioned above), with grain barges arriving here regularly until 1998.

Back on the Severn, Upper Lode Lock was a slightly later addition than the others we’ve seen; it’s even bigger than Diglis, and a rather irregular shape, with the chamber extended by an additional basin so that it could take a tug and its entire tow of unpowered lighters in one locking. Narrowboats are rather dwarfed by it!

Approaching the huge Upper Lode Lock

Perhaps more importantly, from this lock onwards the Severn is sometimes influenced by tides – basically any tide that’s high enough to make a level at the weirs near Gloucester will affect this length for some time around high water. The lock keeper will be able to advise if that’s the case. If it is, allow for the tidal currents, and for the changing water levels if you’re tempted to tie up – fortunately several riverside pubs on this length (like the upper length, the lower reaches of the river are well-supplied) have pontoon moorings.

The wide and meandering river passes Deerhurst, Apperley and Ashleworth villages (all of them keeping a little way back from the banks to stay off the floodplain), before splitting in two a couple of miles upstream of Gloucester at the Upper Parting. Make sure to take the lefthand (ie eastern) channel here – and also be aware that the channel becomes much narrower with several fairly sharp bends, and passing large craft may need some care. It’s also a good idea to phone the lock keeper at Gloucester Lock (a riverside sign gives the number) to warn of your approach.

Leaving the Severn and entering the lock leading into Gloucester Docks

The reason is that the keeper can then have the lock ready for you, avoiding the need for you to stop on the landing stage approaching the lock – which may not be easy when there’s a strong downstream current. If you do need to stop while going with the flow, make sure to secure your stern line first, to avoid the current swinging the boat around.

This is the entrance to Gloucester Docks, and it’s where we leave the River Severn: the remainder of our journey is on a very different waterway, the Gloucester & Sharpness Canal.

Image(s) provided by:

Martin Ludgate