It may not be the easiest waterway to get to, but it’s worth it to explore this fine rural Surrey and Hampshire route which was rescued from dereliction

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

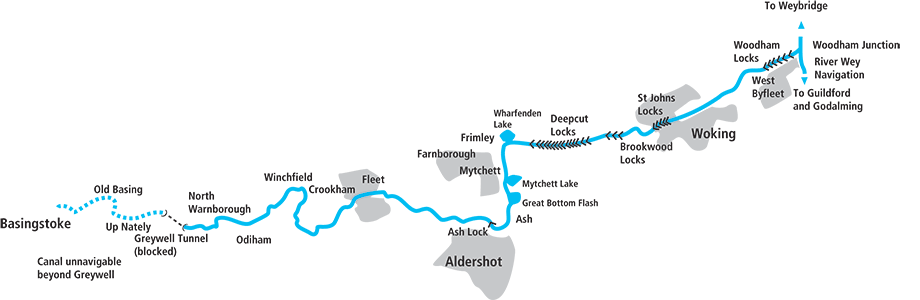

If I begin this cruise guide by detailing the timings, paperwork and other issues that are involved in a trip up this 30-mile waterway, there’s a danger that you might be put off visiting it at all. So I won’t: I’ll instead begin by saying that the Basingstoke Canal is 30 miles of waterway passing through glorious heathland, woodland and countryside scenery, interspersed with some superbly situated flights of locks, and enlivened by assorted quirky historic features along the route – from a lake where flying-boats were tested to a railway built specially for funeral trains.

Although I’ll admit to being ever so slightly biased in favour of the canal as a result of having cut my teeth as a canal volunteer working on its restoration in the 1980s, I think it’s fair to say that a cruise on the canal is most definitely worth whatever complications it might entail. But let’s mention those complications now: unfortunately the canal doesn’t have a very robust water supply – partly because it never did, and partly because some of what it did have was lost when the final few miles beyond Greywell became disused. So, although the Basingstoke Canal Society (successor to the group that led the restoration) has installed back-pumping systems which have greatly helped the water supplies to the eastern end of the canal, it still tends to often run short in summer.

Making best use of the water

That means firstly that it’s a good idea to plan your visit for earlier in the year, so it’s less likely to have been hit by closures or restrictions. And secondly, that to make the best use of what water it has, at all times of year the Basingstoke Canal Authority operates the flights of locks on certain days of the week, and boaters need to book their passages through them, so that staff can seal up the gates with ashes when they’re not in use.

And yes, I did say the Basingstoke Canal Authority – no, it isn’t part of the Canal & River Trust network. So you’ll need a visitor licence from the BCA (which is owned by Surrey and Hampshire councils, the two authorities that bought out the derelict canal in the 1970s so that it could be restored) – and you’ll also need to show an insurance certificate. Oh, and you’ll have arrived via the River Wey Navigation (run by the National Trust), which you’ll have reached from the canal system by taking the River Thames (Environment Agency), so this may well be your third successive visitor licence. But the good news is that if you’re only using the Wey to get to the Basingstoke (although we would encourage you to consider cruising the rest of this attractive river if you have the time – see last month’s cruise guide) you can save money with a ‘transit licence’.

Climbing to Woking

So, having acquired the necessary paperwork and presented yourself and boat at Woodham Junction at the allotted time, your journey begins with the flight of six Woodham Locks – but before you reach the first one, look out for a small modern building on your left. This is the Pete Redway Pumping Station, which pumps water up the six locks, forms the first of the Canal Society’s improvements to the water supply, and was named after the then Chairman and a leading light of the restoration, sadly no longer with us.

The locks are wide beam like most locks on our southern waterways, and widely spaced as they lead upwards and westwards between lines of trees on both sides. These shield the canal from its surroundings, disguising the fact that it’s actually passing through housing estates on the fringes of West Byfleet, with its useful shops a short walk from the canal.

This continues beyond the locks, with trees and vegetation lining the canal as it threads its way through Sheerwater to Woking. This is the only major town on the route, and there are useful moorings convenient for the town centre. Look out for the statue of Surrey County Cricket Club and England bowler Sir Alec Bedser created as a feature of a new footbridge providing access to the town. And if you’re in town, do look out for the giant ‘Martian’ – a re-creation of one of the ‘fighting machines’ which wreaked havoc in HG Wells’ book War of the Worlds, whose action began when the aliens landed on nearby Horsell Common.

Leaving the town centre behind, the canal soon reaches the next flight of locks, known variously as St John’s or Goldsworth. St John’s was a separate settlement that has now been absorbed into Woking but still has some useful facilities. Like Woodham, the locks are shielded from modern housing by a narrow strip of woodland – and they are also supplied by a backpumping scheme built by the canal society, giving this end of the canal a more reliable water supply.

Into the Surrey heathland

Five more locks climb past St John’s

The canal finally escapes the outskirts of Woking, and enters the first of the heathland which characterises much of the next part of its route. The next three locks are at Brookwood – and they, along with the Deepcut flight, are currently open on different days of the week from St John’s Locks, so you’ll end up spending a night on the section between St John’s and Brookwood.

A little way to the south of the canal is Brookwood Cemetery, opened in the 1850s to help provide for London’s needs when the capital’s original city burial grounds were full up and being closed. It isn’t just the country’s biggest cemetery, it’s worth a visit as a Grade 1 listed historic park and gardens – and it was once served by its own railway. The London Necropolis Railway had its one building and platform adjacent to London’s Waterloo Station, and trains of hearse cars and mourners’ carriages went down the main line from there to Brookwood, where a short branch line served two stations in the cemetery – one for Anglicans; the other for nonconformists.

That wasn’t the only former railway branch line in the area: as you reach the next flight of locks after another mile at Deepcut, you may spot the abutments of a former bridge which carried a branch line into Pirbright barracks. Yes, we are entering the area of the Surrey / Hampshire border which has seen a great deal of military presence over the years. This has actually helped to preserve the attractive heathland and woodland surroundings of the canal from development (although the occasional sounds of gunfire not very far away can be disconcerting to those not expecting them!) and the upper locks in the flight of 14 are in a particularly attractive setting, with just a nearby railway line for company.

Look out for Cowshot Bridge below Lock 17: a plaque records that it was rebuilt during the canal’s restoration, and I remember that at the time it was noted that this was a rare case of a traditional brick arched hump-backed bridge being built in the 1980s.

Lock 28 at the top of the flight is accompanied by a dry dock, and marks the end (or very nearly the end) of the long climb from the River Wey. It leads to the long, straight, deep cutting which gives its name to Deepcut, and which ends at Frimley Green, where the canal turns south to cross an unusual four-arch aqueduct over a main railway line.

Deepcut Locks are particularly attractively situated

The curious lakes of Mytchett and Ash Vale

This marks a change to the canal’s character. For the next few miles it runs along a hillside above the Blackwater Valley, and this has resulted in an unusual feature. The canal passes through several lakes, some quite sizeable – and one of them rejoicing in the name of Great Bottom Flash. Some are believed to be flooded former gravel pits, but others are simply a result of the canal’s hillside course. Basically the left (uphill) bank follows the winding contours of the hillside, while the right (downhill) bank was built to follow a much straighter course, resulting in irregular widenings and narrowings of the canal.

There are stories of the lakes being the scene of some interesting activities, involving flying boats in particular – either they were used for testing British flying boat floats, or alternatively barges were moored on the lakes to stop German flying boats from landing there. Nobody knows for sure, but some interesting remains were pulled out of the water back in the 1960s. Today the lakes are a graveyard for one or two old working boats, but probably more importantly also a wildlife habitat. In fact on that subject, the whole canal is regarded as important for nature conservation (including a large number of different species of rare aquatic plants, plus dragonflies and other invertebrates) – to the point where in the past there have been concerns that this would lead to overly strict limits on boating. As it turns out, for other reasons including the limited water supply, the number of visiting craft has never reached the levels where it might be an issue for wildlife.

The unexpected vast expanse of Mytchett Lake

But back to the canal and lakes through Mytchett: it’s a very attractive length, but there’s the odd reminder that it’s not always been an easy one to maintain. Look out for a plaque commemorating the 12,000 sandbags and 280 tons of aggregate that members of the Royal Corps of Transport laid as part of bank protection works during the canal’s restoration in 1979.

And speaking of plaques, there’s another one to spot at Frimley commemorating the 1991 reopening of the restored canal by the Duke of Kent. Finally on this interesting section, there’s the BCA’s Canal Centre at Mytchett.

Canal Centre

Canal Centre

Situated at Mytchett, the canal centre includes a display about the Basingstoke Canal, a café, small gift shop, plus boater facilities, small boats to hire and a trip-boat, and an outdoor play area and picnic area.

Crossing the Blackwater

At Ash, the canal’s character changes again as it swings westward to cross the Blackwater valley on a long embankment. Since the 1990s there’s also been an aqueduct over the then new A331 Blackwater Valley Relief Road – and this caused a certain amount of controversy at the time concerning how the canal would cross the road. Early on, there were even some suggestions that the canal would drop down via new locks, pass under the road, and climb back up via more locks – not a very clever idea, given the water supply issues. Then there was a proposal for a cable-stayed aqueduct (the first in the world?) which raised concerns locally about the height of the suspension tower. In the end, the result was a concrete aqueduct with more styling than many such modern structures but I do wonder if they missed a chance to do something bolder…

Not far beyond is the final lock, Ash Lock, which is open with no restrictions or booking requirements, and brings the canal to its summit level. Yes, it’s level all the way from here for 18 miles to the limit of navigation. That’s not to say that it lacks interest by any means: it’s a winding, meandering rural route passing through attractive scenery all the way, plus attractive villages, one town – and a few navigation features that require some care…

During the time that the canal was moribund, three low bridges were built across it, which are among the lowest on the navigable network. Narrowboats will generally fit, but you may need to clear everything off the roof. The first is the tightest: Wharf Bridge is quoted at just 5ft 10in headroom, although it actually varies a little from one side of the canal to the other. If you make it through, you should be fine at Pondtail Bridge and Reading Road South Bridge.

Tight squeeze under Wharf Bridge, first of three low ones on the canal

A military presence

There’s been more military presence in this area, including Farnborough airfield on the north bank and barracks on the south, and it’s left a couple of interesting relics in the form of two metal bridges over the canal, one carrying just a pipe. An interpretation board explains that these are rare examples of prefabricated army-built bridges, like the better-known Bailey Bridge design. And concrete and brick ‘pill boxes’ on the canalside – plus the odd set of ‘dragon’s teeth’ tank traps – remind us that the canal was also (like the Kennet & Avon Canal and upper Thames) one of the strategic lines that might have been defended in the event of an invasion during the Second World War.

The surroundings have been largely rural since Ash, but now the route passes through Fleet, with the town centre just north of the canal in easy walking distance.

Rural meanderings

The canal now returns to the countryside for the entire remaining length, a particularly meandering section winding its way past Crookham, Dogmersfield, Winchfield and Odiham villages, all with pubs within walking distance. Odiham Wharf is one of the few boatyards on the canal, then the final length leads to North Warnborough and a rare liftbridge – opened with a Canal & River Trust ‘Watermate’ key.

The ruin of Odiham Castle stands just a little way back from the north bank of the canal, and marks the limit of navigation with room to turn round. It may seem that the canal ends in the middle of nowhere, but just ten minutes’ walk down the towpath beyond brings you to Greywell village, and another pub.

ODIHAM CASTLE

ODIHAM CASTLE

Also known as King John’s Castle and built in the early 13th Century, this may well be where King John rode out from to sign (or rather, seal) the Magna Carta at Runnymede. Involved in wars with the French in the following centuries, by 1605 in was a ruin, and today just part of the keep and some earthworks survive

Of course the canal didn’t always end here – and our ‘Cruise Guide Extra’ on the following pages traces the remains of the final length to Basingstoke. But even without those lost western reaches, I hope you’ll agree that the 30 navigable miles have been well worth visiting.

As featured in the April 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the April 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here