Part river and part canal, this waterway combines large locks built for modern freight transport with 200-year-old waterways heritage, and industrial surroundings with splendid wooded valley scenery

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

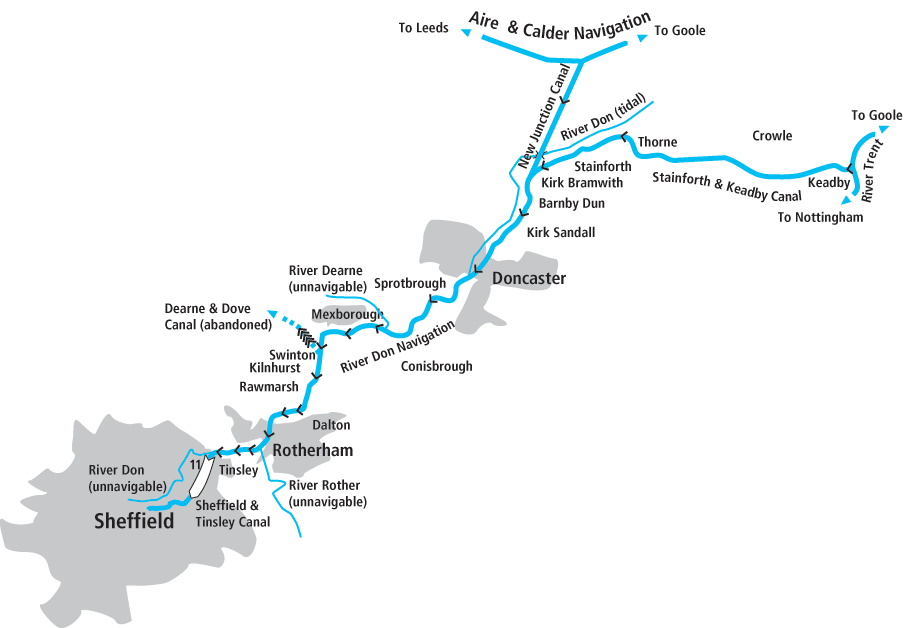

To describe the Sheffield & South Yorkshire Navigation as a ‘river-based waterway which makes use of the River Don’ would be true – but it would also be an oversimplification of a rather more complicated situation. To illustrate my point: at its west end, the Navigation takes the form of a three-mile artificial canal which terminates at a basin in Sheffield city centre. And at its east end, it follows another artificial canal for a rather longer distance before meeting the tidal River Trent at Keadby – while the actual River Don has diverged quite some miles northwards to meet the Yorkshire Ouse near Goole.

And in fact many (perhaps most) visiting boaters to this interesting Yorkshire waterway arrive via a third arm, the (also completely artificial) New Junction Canal, coming southwards from the Aire & Calder Canal via Sykehouse to meet the S&SYN Main Line at Bramwith. And yet in between these three extremities, it does function as a river navigation, and boaters will find themselves cruising along lengths of the River Don, from the wooded and rural to the urban and industrial.

To help make sense of this complex route, let’s first look at its history. The lower reaches of the River Don below Doncaster were naturally navigable in Mediaeval times given favourable tides. Near Thorne, the river split into two channels: one headed due north to join the River Aire, while the other meandered north eastwards to meet the River Trent. Neither of these was a reliable navigation, but in the 17th Century, the Dutch engineer Cornelius Vermuyden created a new straighter single channel (still known as the Dutch River) which carried the River Don’s water from Thorne to the River Ouse just east of Goole.

Thorne Lock, whose short chamber prevents full-length narrowboats from getting through the Stainforth & Keadby Canal

By the end of the 17th Century, plans were being made to extend navigation upstream from Doncaster by building locks – but it was 1751 before the first boats continued through Rotherham to Tinsley, a few miles short of Sheffield. Half a century later, the independent Stainforth & Keadby Canal provided an outlet to the River Trent, bypassing the tricky and dangerous tidal Dutch River section. And in 1819, another independent concern built the Sheffield Canal, three miles long with 12 locks, taking boats from Tinsley to the heart of the city.

Come the 19th Century, and one might have expected the Don Navigation to develop like its prosperous neighbour the Aire & Calder Navigation – with lock enlargements, straightening and deeper dredging, and steam tugs pulling long trains of ‘compartment boats’ carrying hundreds of tons of coal. But it didn’t quite work out for the Don. Yes, there were improvements, with new sections of canal bypassing lengths of river, but unlike the A&C, the Don came under the control of a railway company which didn’t encourage trade.

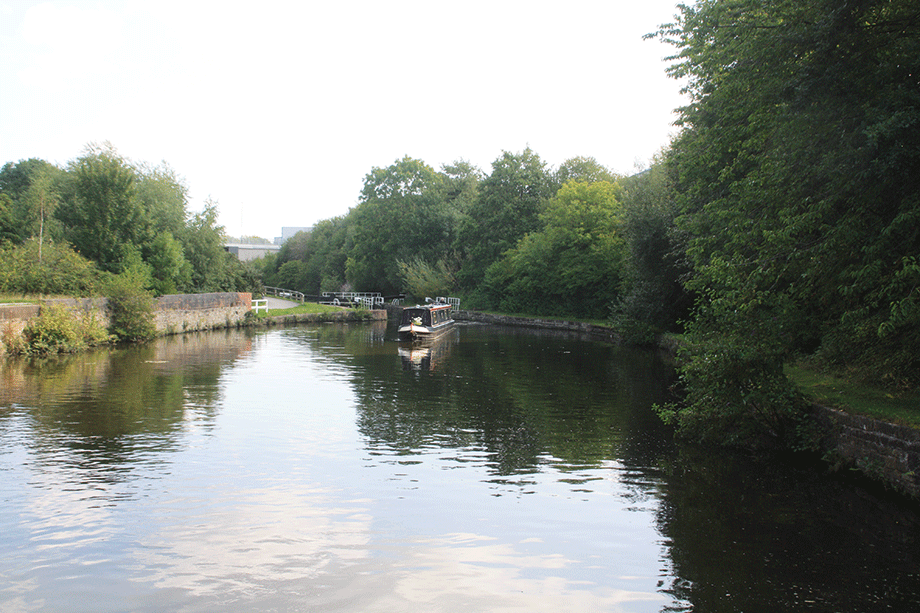

Beginning the climb up the Tinsley flight of eleven locks

By the 1880s, it was still reliant on horse haulage for its 62ft by 15ft barges carrying around 100 tons.

An 1890s scheme to take the Don and connecting canals out of railway ownership saw them regain their independence as the combined Sheffield & South Yorkshire Navigation, and a new high-capacity link, the New Junction Canal, was built to connect their waterway to the Aire & Calder. But there was little money left for enlargement of the existing locks, while appeals for Government support fell on deaf ears – so there was only piecemeal rebuilding of a few locks from Stainforth to Doncaster.

Belatedly – many would (with hindsight) say it was ‘too little too late’ – a programme that began in the late 1970s, saw the lengths from Doncaster up to Rotherham rebuilt with new powered locks capable of taking 700-ton craft by 1983. But sadly, much trade had already left, and it proved difficult to persuade it to return. In 2014, concerned that large-scale freight on its waterways nationally had dwindled to just three regular traffics including lubricating oil carried on the S&SYN to Rotherham, the Canal & River Trust identified the waterway (along with the Aire & Calder and River Ouse) as ‘priority freight routes’ worthy of further work to encourage trade. But it has yet to bear fruit. But while these waterways’ cargo-carrying future may be in doubt (albeit the oil trade has re-started after a gap), leisure boaters are still welcome. The large waterways provide a completely different landscape to the narrow canals of the Midlands, very worthy of exploration. And we’ll begin exploring them not at the junction with the Trent, nor at the Sheffield terminus, but via the third arm, the New Junction Canal, which we’ll enter from the Aire & Calder Navigation.

Why are we starting there? Because it’s the route by which many visiting boaters will arrive, as it’s the point of entry for those who’ve come via any one of the three trans-Pennine waterways (Leeds & Liverpool, Rochdale or Huddersfield) rather than the perhaps more adventurous route via the tidal Trent.

To use its full name, the Aire & Calder and Sheffield & South Yorkshire New Junction Canal must be a contender for the title of ‘shortest canal with the longest name’. It was also one of our last to be built, opened as late as 1905. It’s certainly the straightest, running near enough dead straight for five miles from Southfield Junction to Bramwith Junction, and it was built from the start for large barges and strings of compartment boats. It begins in a rather empty landscape – there’s no actual village of Southfield, just a small reservoir of that name – which doesn’t hold out much for the prospects of an interesting cruise. But in fact it has several notable features.

The first is an aqueduct over the River Went, followed by a series of six liftbridges and swingbridges interrupted by Sykehouse Lock (powered and boater-operated using Canal & River Trust ‘Watermate’ key, as are the bridges), before another larger aqueduct crosses the River Don. It’s protected by large guillotine gates at each end which are used to close off the navigation and keep flood water out of it if the river level rises high enough to overflow into the aqueduct.

The canal meets the main line of the Sheffield & South Yorkshire Navigation at an oblique junction, where we’ll first turn sharp left to head eastwards towards the Trent.

We’re now on a length whose origins were in the River Don Navigation, but later improvements and extensions of the length of artificial canal mean that we don’t actually join the river at all. Its tidal channel is visible to our left as we pass Bramwith Lock (extended in the 1930s from its original 62ft to a much larger size) to reach Stainforth. At this handy town, the first since we began our cruise, we join what was built as the independent Stainforth & Keadby Canal, although it continues to parallel the River Don with no obvious changes. But around Thorne, the river diverges to the north while the canal continues east.

Thorne was once a great boatbuilding town (and still has a selection of boatyards and marinas as well as pubs and shops), as well as being the site of an unusual feature of the local waterborne trade. Sailing craft coming up the tidal Don would leave their masts here for safekeeping and carry on horse-drawn towards Doncaster.

There’s a lock here, and it’s a highly significant one for boaters in longer craft, because unfortunately (and unlike all the other locks between the Trent and Rotherham) it retains its original dimensions of around 62ft by 17ft. The exact maximum length will depend on hull shape, but a full length narrowboat won’t fit – see Boaters Notes for the implication of this restriction.

Leaving Thorne, the canal takes a quiet course across flat countryside with just a railway for company, passing a series of swingbridges and a solitary settlement of Ealand.

Approaching Keadby, the railway crosses on a remarkable and possibly unique (at least in this country) opening bridge. Instead of lifting or swinging, this oblique bridge slides diagonally out of the way (it’s much easier to understand if you see it than to try to explain it!) under the control of the adjacent signal box to allow boats to pass.

The final length leads into Keadby, now sadly without pubs, where the tidal lock leads out onto the tidal Trent. As mentioned in the Boaters Notes, many inland boaters venture safely onto the tideway with appropriate precautions; but we’ll turn around, return to Bramwith, and this time we’ll continue southwest at the junction, towards Doncaster.

Approaching the liftbridge at Barnby Dun

This section, like the length between Bramwith and Stainforth, has its origins in the Don Navigation, but it too has since been straightened, enlarged and improved, and now makes no use of the river channel. The route passes Barnby Dun (‘Dun’ was an old spelling of Don) village and Long Sandall, where a lock begins the climb towards the hills. Like all the locks from here to Rotherham it’s a large, modern, power operated lock, created for heavy freight traffic which might one day return. And as with all the locks, it’s no longer staffed but operated by CRT key.

The navigation meanders its way along the Don’s floodplain, accompanied by the river and an assortment of railway lines as it approaches Doncaster. There are visitor moorings on the left before town centre that are convenient for the town, a former mining, industrial and railway centre with good shops, a market, pubs, and historic buildings worth a visit.

A flurry of rail and road bridges cross the waterway at and around Doncaster Town Lock, then the town is soon left behind as the development on either side keeps clear of the river’s floodplain. And after half a mile, we join the River Don for the first time, as the waterway finally remembers its roots as a river navigation.

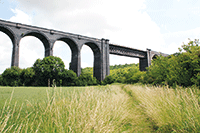

Conisbrough Viaduct

Conisbrough Viaduct

The steep-sided Don Valley is spanned by the impressive 113ft high Conisbrough Railway Viaduct, opened in 1909 to carry the Dearne Valley Railway. The line closed in 1966 but the viaduct is now a foot and cycle path and well worth the steep climb from the riverside to enjoy panoramic views over the river and valley.

Forget anything you may have heard about the S&SYN being gritty or industrial: the next few miles feature a series of splendid wooded reaches as the river threads its way through a deep, steep sided valley. Yes, there are reminders of its industrial past in the form of a series of railway viaducts, some quite spectacular, but it’s a far cry from the ‘grim up north’ cliché.

Sprotbrough village provides handy facilities including a waterside pub, while Conisbrough is a pleasant town with a castle to visit (see below), and the locks continue the gentle climb.

Conisbrough Castle

Conisbrough Castle

The castle, in its prominent position above the river, was built in the 12th Century but fell into ruin 400 years later. It became a 19th century tourist attraction as a result of having been used by Sir Walter Scott as the setting for his novel Ivanhoe, and is now run by English Heritage and open to the public.

More industrial surroundings return at Mexborough and the locks become more frequent as the climb steepens. Waddington Lock takes its name from the once busy barge operating base of EV Waddingtons at Swinton Junction. The junction was where the Dearne & Dove Canal once branched off.

Trip-boat on an attractive length of the River Don above Doncaster

Passing what was an intensely industrial area between Kilnhurst and Aldwarke but is seeing some land reclamation alongside the remaining industries, the waterway reaches Kilnhurst and the approach to Rotherham. Eastwood Lock is the last of the large locks completed in the early 1980s, and you may notice a widening of the channel half a mile further on: this was to allow the 200ft barges that the new locks were built for to turn.

The lengthy Rotherham Cut runs through the town centre, and part of it is currently a focus for a town regeneration masterplan, with new developments planned for the land between the Cut and the river. And above Rotherham Lock, a rather striking and to my mind, quite stylish new flood barrier gate (and those aren’t words you often hear together!) has since 2022 protected this area from flooding when the river is high.

Entering Mexborough Top Lock, one of the series of new 200ft long mechanised locks built in the 1970s-80s enlargement for larger freight barges

This lock is the first of the old-style locks, manually operated and built for barges 62ft by 15ft – although a somewhat longer single narrowboat may pass through. Three more such locks follow in the next mile and a half as the climb steepens again. A final short river length leads to Tinsley, where navigation and River Don part company for the last time as we enter the Sheffield Canal.

The eleven closely-spaced Tinsley locks climb to the canal’s summit level; there were once 12, but two were combined in connection with a railway scheme in 1959 – you’ll notice that one lock is now a lot deeper than all the rest. You may also spot a plaque recording the destruction of one of the locks in by a bomb in the Second World War. And you might see signs of more recent upheavals: the canal has always relied on backpumping of water to supply the locks, as fierce opposition from Sheffield’s industries reliant on the river to drive their waterwheels meant that none could be spared to feed the canal. And in recent years, the pumping system has had to be rebuilt, involving temporary pumps and lengthy towpath closures while the buried pipes were replaced. The three-mile summit level leading into Sheffield was once surrounded by the steelmaking and other industries that made the city famous. But although there’s still plenty of industry left, nature has been gradually taking over the watersides and shielding the canal, leaving it with an unkempt but not unattractive appearance. Look out for Darnall Road Aqueduct, surely one of the least well-known aqueducts on the waterways.

On the summit of the Sheffield Canal section, heading through the city’s industrial outskirts

A sharp turn near the very end leads into Sheffield’s Victoria Quays, a fine city centre terminus basin with new uses found for old buildings, including an impressive five-storey warehouse spanning the basin, cafés and other businesses set in the adjacent former railway arches, and moorings to tie up and explore the city’s attractions with much within easy walking distance. It’s a good way to end a journey up an interesting and varied waterway.

BOATERS’ NOTES:

Longer craft: The two usual ways that visiting craft from outside the north eastern waterways reach the Sheffield & South Yorkshire Navigation are either via one of the three trans-Pennine canals or via the tidal Trent to Keadby (a tidal passage to be treated with caution, but perfectly safe in suitable inland craft in experienced hands, with the appropriate charts and tide tables). However, neither of these is possible in boats longer than a little over 60ft (the exact limit depends on hull shape), owing to short locks on the Leeds & Liverpool Canal, Calder & Hebble Navigation, and at Thorne on the Stainforth & Keadby Canal. The only way to get there in a full-length 70ft narrowboat is to continue down the tidal Trent beyond Keadby, right down to Trent Falls where it meets the Yorkshire Ouse at the head of the Humber estuary, then up the Ouse to enter the Aire & Calder Navigation at either Goole or Selby, then the New Junction Canal to reach the S&SYN at Bramwith. This is an adventurous journey involving anchoring at Trent Falls (where the river is around half a mile wide) to wait for the tide, and tackling it requires experience, good knowledge of local waters, and suitably reliable, powerful and well-equipped craft (including marine band radio and a qualified operator). Once you get there, you will be limited to the Thorne to Rotherham length by lock sizes. Tinsley Locks are limited by CRT to craft no longer than 60ft.

Locks and opening bridges: Mechanised locks from Long Sandall to Rotherham and on the New Junction Canal are operated by a Canal & River Trust ‘Watermate’ key, as are lift and swing bridges.

Bookings: Boaters planning to use the tidal Trent via Keadby to get to or from the S&SYN will need to book in advance with the lock keeper. Tinsley Locks on the Sheffield Canal will also need to be booked in advance.

River conditions: The waterway between Doncaster and Tinsley makes use of the River Don. Boaters should make the usual allowance for currents, and if river levels rise after heavy rain they should be prepared to tie up somewhere safe and wait for levels to fall again.

As featured in the May 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the May 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here