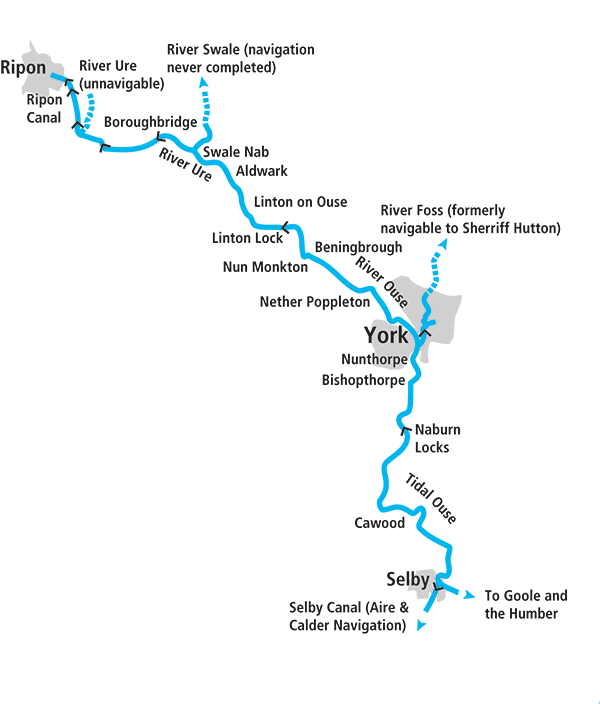

From Selby we head northwards through York and Boroughbridge to reach Ripon, on the fringes of the Pennines and one of the northern outposts of the waterways network.

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

We begin our guide to the Yorkshire Ouse and associated waterways at Selby, the usual place where visiting inland waterways craft join the river, via a connection to the Selby Canal branch of the Aire & Calder Navigation, which we covered in last month’s cruise guide.

We begin our guide to the Yorkshire Ouse and associated waterways at Selby, the usual place where visiting inland waterways craft join the river, via a connection to the Selby Canal branch of the Aire & Calder Navigation, which we covered in last month’s cruise guide.

A rather different river

But apart from both being river based, both situated in Yorkshire, and sharing this meeting point at Selby Lock, there isn’t much that these two waterways have in common. The Aire & Calder ran through heavily industrialised country and spent two three hundred years being expanded, modernised, straightened and many of its river sections being bypassed by new canal lengths, to the point where it was still a commercial freight artery busy with 600-ton barges until quite recent times – and even today carries some freight. By contrast, the mainly rural River Ouse is still the largely unimproved natural river made navigable in the 18th century when its small number of locks were first built, and retains its original dimensions.

Speaking of which, we should point out here that you won’t get to the top of the river in a full-length narrowboat. Like many northern waterways the Yorkshire Ouse was made navigable for typical local river craft which tended to be wider but shorter. In this case, the maximum dimensions are around 57ft 6in by 14ft, although a slightly longer narrowboat would get through.

Those limits won’t affect us just yet – Selby and Naburn locks are plenty long enough for a full-length narrowboat, and (having managed to get it to Yorkshire in the first place, which for longer boats means an adventurous trip around Trent Falls) it’s well worth it just to visit York.

Tackling the tideway

Another difference between the Yorkshire Ouse and the Aire & Calder at Selby which you’ll need to be aware of straight away is that the Ouse here is a tidal river, with quite a big range and strong tidal currents. You’ll need to time your journey so that you leave Selby when there’s enough water for the lock to operate, and when the tide is coming in and the current will help you on your way towards York. In winter (mid-October to late February) you’ll need to book 48 hours in advance with the lock keeper; at other times of year it’s a good idea to phone the keeper before you arrive anyway, to discuss timings. There is also helpful advice available in the form of CRT’s Planning a safe passage on the River Tees and River Ouse (available online) and The Boating Association’s detailed chart of the Ouse (part of the Trent Series) which can be bought online or from lock keepers.

If you do arrive at Selby and find that you need to wait until the next day for a suitable tide, it’s not a bad place to spend some time, with good shops, a selection of pubs, and the historic Selby Abbey.

Leaving the lock (again, take the keeper’s advice), you’ll turn sharp left into the river and need to be alert on the tiller straight away as the tide will immediately carry you under two swingbridges: one rail and one road. Today, the railway bridge carries mainly local and regional services to Hull, but until a diversion opened in 1983 it was part of the East Coast Main Line, which must have been awkward if many boats needed it swinging open. Fortunately, narrowboats and other typical inland craft will generally fit under the bridges with plenty of room to spare.

The river takes a sharp right turn, and Selby is soon left behind as it heads northwards between high banks, through flat and rather empty countryside.

Cawood Swing Bridge, the only bridge between Selby and Naburn

The only settlement on the tidal length is Cawood (with another swingbridge which inland craft won’t need opening), but you wouldn’t be wanting to moor on the tidal length anyway.

The 15 miles of winding tidal river come to an end at Naburn Locks. These, like Selby, are keeper-operated, only open at certain states of the tide, and need to be booked 48 hours in advance in winter (and it’s a good idea at any time). It’s also a good idea to phone (or radio, if you have marine band VHF) ahead to confirm that you’re approaching the lock, so the keeper can have it ready. This is rather more important on the return journey, when approaching Selby Lock, as there’s less room to manoeuvre and the tide will be faster, so it’s a good idea to ensure that the lock’s open.

On the non-tidal reaches above Naburn

National Railway Museum

National Railway Museum

Historic steam, diesel and electric locomotives and rolling stock on display (including Mallard, the world’s fastest ever steam engine and a Japanese bullet train), with around 100 major exhibits telling the story of rail transport. It’s just one of the attractions of the city of York, which also include the Minster, the Yorvik Viking exhibition, the city walls, and the Castle Museum.

Passing through York

Having left the excitement of the tidal passage behind you, there’s an enjoyable five miles of wide, meandering river leading past Bishopthorpe to York. As you approach the city centre, look out for the entrance to the River Foss on your right: this is still navigable for around a mile and a quarter by intrepid boaters who don’t mind reversing part of the way back (if they’re in anything longer than about 36ft); the one remaining lock is operated by volunteers from the local branch of The Inland Waterways Association, but you’ll need to email castle.mills@waterways.org.uk and give 48 hours’ notice.

Lendal Bridge, with York’s visitor moorings beyond

Skeldergate Bridge marks the start of the city centre, still mostly surrounded by the city walls, and with the Minster, the Shambles, and all the city’s other attractions within easy reach. But you’ll need to carry on right through the centre – a splendid stretch of urban waterway – to just past Lendal Bridge to find the visitor moorings and walk back into the city.

Passing the National Railway Museum on the left, the river continues northwards, York’s suburbs staying a sensible distance from the Ouse (given its occasional tendency to flood) and giving the impression of being back out in open countryside almost immediately.

The river follows a rather straighter course north-westwards, passing Beningbrough to reach the delightfully named Nun Monkton, where at Monkton Pool the unnavigable River Nidd enters (watch out for shallows here) while the Ouse turns sharp right.

Converted Yorkshire Keel barge moored near Beningbrough

Linton Lock, something of a boating centre – and the limit for longer craft

The narrower upper reaches

A considerably narrower stretch of river leads past Newton-on-Ouse to where the long lock-free section finally comes to an end at Linton Lock. Having had something of a chequered history – it was run by a separate authority (the Linton Lock Commissioners) for many years, and had to be rescued from falling into dereliction more than once due to their lack of funds – the lock is now run by the Canal & River Trust (as is the entire non-tidal river), and is something of a boating centre with marina, boatyard, café bar and facilities. It’s also the first of the short locks: any boats longer than about 57ft 6in (the exact limit will depend on beam and hull shape) will need to turn here; there’s plenty of room for this below the lock.

The Devil’s Arrows

The Devil’s Arrows

Situated in a farm field on the edge of Boroughbridge and visible from a public right of way a half mile walk from the river, this group of Mesolithic or Bronze Age stones might not the most exciting arrangement (there are just three of them) but one of them is the second tallest standing stone in Britain, and bigger than any at Stonehenge

A change of identity

A couple of miles further upstream, the river undergoes a transformation – but not an obvious one. You may have noticed that the title of this article mentioned the River Ure as well as the River Ouse: this is in fact a name change which occurs where a small stream called the Ouse Gill Beck enters the river from the west. From now on we’re on the River Ure.

Another five miles of quiet waterway (with just one road bridge, the slightly rickety-looking wooden-decked Aldwark Toll Bridge) lead to Swale Nab, where the river Swale enters from the north east. There was an unsuccessful attempt to make this fully navigable.

Three more miles of winding river bring us via Milby Lock to Boroughbridge, the first place of any size since leaving York. Once an important staging post on the old Great North Road midway between London and Edinburgh, it’s a fine old market town with plenty of shops, pubs, restaurants, and a local museum. Passing the town via the artificial Milby Lock cut, the navigation rejoins the river to pass into slightly hillier countryside, as the flat Vale of York is gradually left behind. Westwick Lock continues the very gentle climb, and on the right you can catch a glimpse of Newby Hall, a fine country house in extensive gardens and open to the public.

Ripon Cathedral

Ripon Cathedral

Originally an important church in the Diocese of York, it was upgraded to a cathedral in 1836 when Ripon became a city and diocese in its own right. The building dates from the 13th to the 16th centuries, with a Saxon crypt dating to 672 which is the oldest structure still in use in any English cathedral.

The Ripon Canal

Entering the Ripon Canal and approaching Oxclose Lock

From there it’s only another mile until another change of waterway: we reach the limit of navigation on the Rive Ure, and our route continues via the Ripon Canal which bears off on the left to enter Oxclose Lock. Barely two miles long and built to link the river to the city of Ripon (itself one of our smallest cities), this is one of our shortest canals, but also one of the northernmost on the national waterways network (only beaten by the opening of the Ribble Link, bringing the Lancaster Canal into the network).

For many years, only Oxclose Lock and a mile of canal beyond were navigable, leading to Ripon Motor Boat Club’s marina (whose members had restored this section), but a restoration project led by Ripon Canal Society saw the remaining mile and two locks reopened in 1996.

An attractive route into the city leads to a fine terminus basin accompanied by old and new housing, warehouse and pub. It’s a fine base to explore this fine, compact city on the fringes of the Pennines, with its cathedral, museums, market, and the Wakeman who can be seen (and heard) blowing his horn at each corner of the market square’s obelisk at 9pm every evening.

Journey’s end: the terminus basin and moorings in Ripon

As featured in the February 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the February 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here