An exception among northern canals, the Lancaster eschews the Pennine moors and runs along the coastal plain, making for a relaxing lock-free cruise with quiet countryside, a passage through historic Lancaster city, and plenty of aqueducts.

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

Following on after April and May’s cruise guides which covered the Leeds & Liverpool Canal, you might expect the Lancaster to be another waterway in the same style, with mill towns, moorlands, and mighty flights of locks. But in fact, it could hardly be more different. There are few mill towns and no moorlands, but it’s still an attractive canal, and a very relaxing one – with no locks at all on the surviving part of the mainline.

Following on after April and May’s cruise guides which covered the Leeds & Liverpool Canal, you might expect the Lancaster to be another waterway in the same style, with mill towns, moorlands, and mighty flights of locks. But in fact, it could hardly be more different. There are few mill towns and no moorlands, but it’s still an attractive canal, and a very relaxing one – with no locks at all on the surviving part of the mainline.

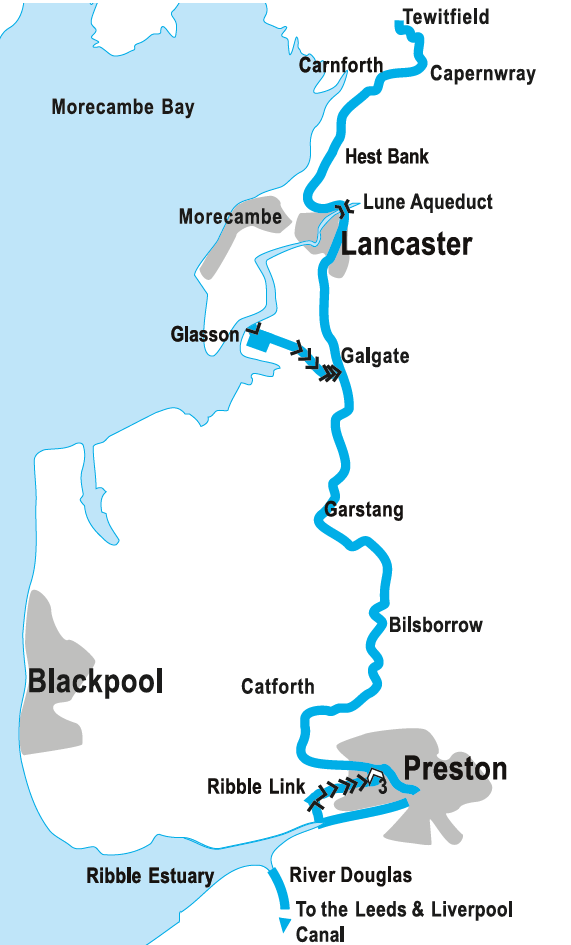

And that’s because unlike the Leeds & Liverpool, which (like the Huddersfield and Rochdale canals too) is an east-west route crossing the Pennines, the Lancaster runs north-south, and is an example of a coastal canal, running roughly parallel to the shore for most of its route. Such canals are rare – in fact only four others in Britain come to mind, and none of them were particularly successful. The Portsmouth & Arundel Canal and the Royal Military Canal were both concerned with avoiding Napoleon’s forces, but by the time they were completed this was no longer a threat. The Tennant Canal in South Wales at least carried a busy trade for a while in combination with the Neath Canal, but went out of use in the 1930s. And as for the eastern length of the Salisbury & Southampton Canal, well, our article about the sad story of this ill-fated waterway was titled ‘Britain’s least successful canal’ – enough said.

By contrast, the Lancaster, with its route running north from Preston along the flat Lancashire coastal plain through Lancaster, before heading inland for its last few miles to Kendal on the edge of the Lake District, was quite a success. Coal carried northwards from mines in south Lancashire was the mainstay of the traffic, but the canal was also notable for the successful operation of ‘swift packet boats’ – passenger boats with streamlined hulls, towed at speed by a team of horses – which covered the entire journey from Preston to Kendal in eight hours. And perhaps the most unusual aspect of its successful early history was that in 1842, when other canals were feeling the pinch of competition from the developing railway network and in many cases sold out to their rival railway companies, the opposite happened on the Lancaster. The struggling Lancaster & Preston Junction Railway company leased itself to the canal company.

Despite this, it wasn’t entirely successful in completing its own route. Preston wasn’t planned to be its southern terminus; it was intended that the canal would cross the River Ribble on an aqueduct then climb a flight of locks and continue southwards via Walton, Johnson’s Hillock and Chorley to Westhoughton, a few miles south east of Wigan and in the heart of the coalfield. But although the southern part of this was built from Walton to near Wigan, the length from Preston to Walton including the locks and aqueduct proved too costly. Instead, a ‘temporary’ horse tramway was built – and in the event, it was never replaced by the planned canal link. The section of canal from Johnson’s Hillock to near Wigan was close enough to the planned route of the Leeds & Liverpool Canal that it was used as part of the L&L’s line (it may seem odd that part of a north-south canal got incorporated into an east-west one, but the L&L’s route wasn’t exactly a direct one at times!) and eventually ownership was transferred.

With the original Preston terminus long abandoned, the canal begins rather in the middle of nowhere

Eventually the final three quarter mile length leading to the original terminus basin in Preston was abandoned and filled in (you can still find traces of it if you go exploring on foot), and the canal now gives a distinct impression of starting in the middle of nowhere, with no actual terminal basin – just a dead end on a slight embankment, where once an aqueduct spanned a road. This ‘middle of nowhere’ feeling is emphasised by the fact that all boats visiting the canal from elsewhere (other than any seagoing craft coming in via the Glasson Dock Branch – see later) will have arrived via the Ribble Link, which joins the canal a mile and a half further on. So that southernmost one and a half miles sees little use – although it’s worth cruising, not just ‘because it’s there’ but to get within walking distance of Preston or to visit the boatyard in a small basin near today’s terminus.

But we’ll assume that you’re starting right at the dead end – and heading out of the town it’s a not unpleasant length running through residential areas, and introduces a couple of Lancaster Canal features. The first is the fine traditional stone-built bridges which carry roads and farm crossings over the canal, and the second is a small aqueduct over the Savick Brook.

One inherent feature of a canal running parallel to the coast – particularly, as in this case, with a range of hills just a little way inland, collecting plenty of rainfall – is that your waterway will have to cross all the rivers and streams coming down from the hills to the sea. And that means that aqueducts, large and small, are a feature of the entire length of the canal. In fact, as we’ve already seen, it was the anticipated cost of one of the larger ones (a three-arch structure was planned to cross the Ribble) that prevented the southern end of the canal from being completed.

Ribble Steam Railway and Museum

Based on some of the old railway tracks that served Preston Docks, the railway offers steam train rides on Saturdays from April to September (plus bank holidays and some other special days), using the sort of small industrial tank engines which would have worked the dock system. The museum displays more of these locomotives and other vehicles.

Based on some of the old railway tracks that served Preston Docks, the railway offers steam train rides on Saturdays from April to September (plus bank holidays and some other special days), using the sort of small industrial tank engines which would have worked the dock system. The museum displays more of these locomotives and other vehicles.

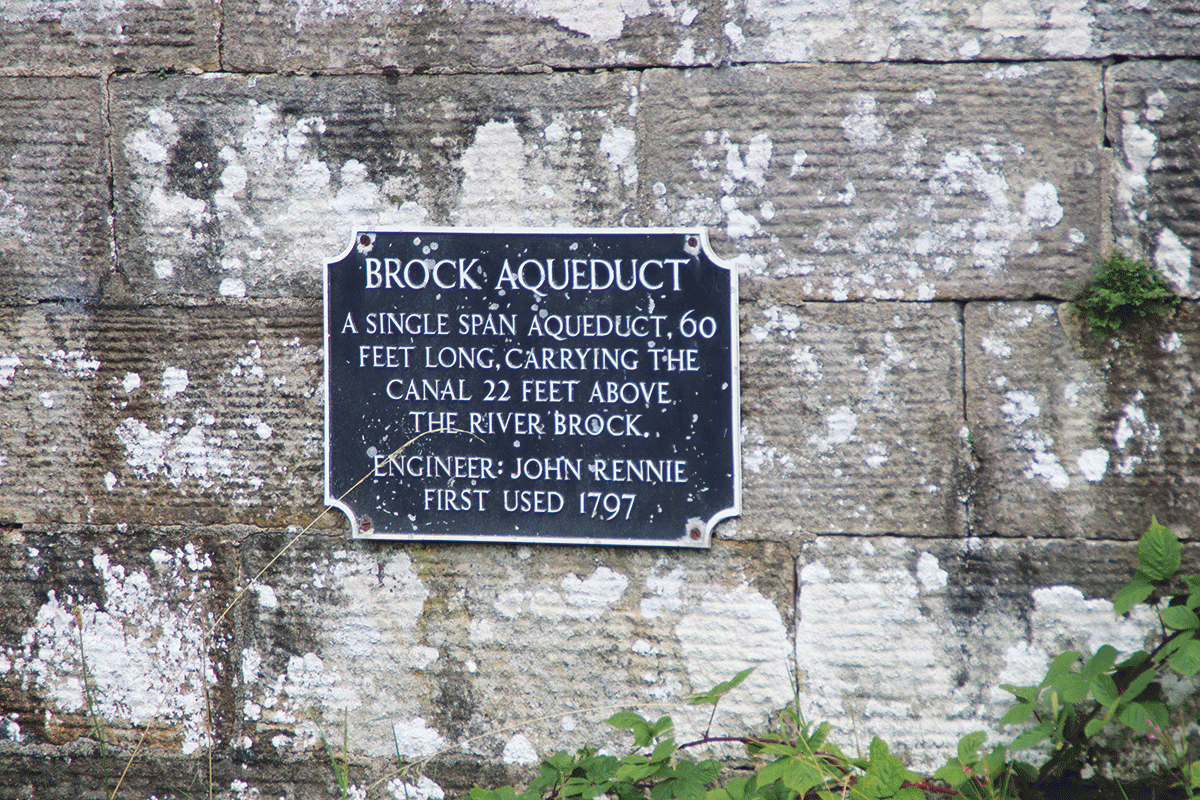

This one by contrast is a more modest single-span construction but, as you can see if you jump off your boat and scramble down the bank (and as we can expect from the canal’s engineer John Rennie) it’s an attractive and well-built structure.

Until 20 years ago our guide would simply have continued with a description of the canal as Preston was left behind and it wound its way roughly northwards. But everything changed in 2002 with the opening of the Ribble Link Navigation, a brand-new waterway which for the first time ever provided an inland link to the Lancaster Canal for boats from the rest of the national navigable network, and which joined the existing canal at a new junction just by the last of Preston’s housing estates.

Getting there

Until 2002 the Lancaster Canal was an isolated waterway, and could only be reached from the main navigable network by going to sea, and entering the Lancaster Canal via the Glasson Dock Branch. But in 2002, the new Ribble Link Navigation opened, creating an inland route to the Lancaster.

It’s still not a straightforward journey, involving a tidal passage that needs boats to be adequately powered for coping with fast tidal currents, reliable, suitably equipped, and with appropriately experienced crew.

The passage is only available from April to September, only on days when there are suitable tides (typically five or six days per month in each direction), and subject to cancellation in the event of strong winds. Passages need to be booked in advance via the Canal & River Trust website canalrivertrust.org.uk – where there is a Skippers Guide available. Maximum craft dimensions quoted by CRT are 62ft by 10ft 6in by 2ft 3in draught.

The first part of the journey from the Leeds & Liverpool Canal involves turning off the main line at Burscough and descending the Rufford Branch to the tidal lock at Tarleton. This part does not need to be booked.

At the appropriate state of tide, boats pass through the tidal lock and descend the tidal River Douglas for four miles to where it meets the Ribble Estuary. Turning right into the Ribble, they head upstream for three miles before turning left to enter the mouth of the Savick Brook. Passing through the tidal lock with its rotating gates, they then climb the eight conventional locks of the Ribble Link, which is a canalisation of the brook.

The final three locks form a staircase, and the entrance is at a very awkward angle. Longer craft will either need to use the turning basin provided, or reverse up the locks.

Above the staircase, a basin leads to the junction with the Lancaster Canal.

Unlike most canals, there are as many cruisers as narrowboats on the Lancaster

You’ll see a few more boats out and about as the canal continues – and you’ll find that they’re rather more of a mixture than on many canals, with narrowboats mingling with GRP cruisers and widebeams. But it’s still a less-than-busy route through quiet countryside. In sharp contrast the lively seaside resort of Blackpool is just a few miles to the west – and you might catch a glimpse of the famous tower if you look out at the right point.

We said that the canal went ‘roughly’ northwards, and at times it’s a very indirect route, heading first west, then north, then east again, so that after eight miles of cruising through what might seem quite remote countryside, you’re actually barely a mile and a half from Preston’s outskirts. Why does it meander so? Largely to reduce the necessary earthworks, as the coastal plain isn’t all that flat in places – in fact despite the winding route we’ve already passed through the first of several gloomy tree-lined cuttings.

Turning to run northwards and crossing a couple more small aqueducts, the canal passes Billsborrow, where the family-friendly canalside Guy’s Thatched Hamlet livens things up with a pub, restaurant, craft shops and play areas. The canal is now running closer to the Pennines, clearly visible to the east; it’s also rather closer to the West Coast Main Line railway and the M6 motorway which disturb the peace for a couple of miles before the canal meanders off westwards towards Garstang. Meanwhile, the series of aqueducts continues, with a couple of slightly more substantial structures crossing the Brock and Wyre rivers.

Plaque commemorates one of John Rennie’s many fine aqueducts

Garstang, the first sizeable settlement on the canal since leaving Preston, is an old market town with useful shops and a selection of pubs, plus a boatyard just to the north. Look out for a curious concrete bridge over the canal with ‘FWB 1927’ cast into the crown of the arch: this carries the water supply from Barnacre Reservoir to Blackpool (FWB stands for Fylde Water Board).

Rural cruising north of Garstang

The surroundings are becoming more hilly, and the canal passes through more cuttings as it winds northwards to Galgate where there is a junction – and the left turn leads straight into the first lock that we’ve come across. Yes, we said that there were no locks today on the main line, but there are six on this arm to Glasson Dock on the Lune Estuary, which until the construction of the Ribble Link formed the canal’s only navigable link to the outside world (and even then, only by going to sea). It still fulfils that role for seagoing craft, but it’s also worth exploring as an out-and-back for inland boats. The locks (with their distinctive paddle gear, similar to some of the unusual types found on the Leeds & Liverpool Canal) provide some exercise and relief for any boaters suffering withdrawal symptoms after so many lock-free miles. And Glasson Dock itself, still a small working port, provides visitor moorings in the inner non-tidal basin, and is one of those interesting ‘canal meets sea’ places (like Tarleton, Sharpness and one or two more) where there are all sorts of craft, and an atmosphere that’s a bit of each. Back on the main line there are more of the gloomy wooded cuttings spanned by some impressive stone bridges as the canal approaches Lancaster.

The canal skirts the eastern fringes of central Lancaster with glimpses across the city of the cathedral and other buildings, visitor moorings and a couple of waterside pubs. A walk into the city centre leads to the castle, city museum, maritime museum and more.

Lancaster Castle

Some 15 minutes’ walk from the canal, the Mediaeval castle was still in use as a prison until 2011, following which it has been restored and opened to the public from Easter to October with guided tours daily.

Some 15 minutes’ walk from the canal, the Mediaeval castle was still in use as a prison until 2011, following which it has been restored and opened to the public from Easter to October with guided tours daily.

While you’re in the area, visit the nearby Cottage Museum, Priory church, and remains of a Roman bath house.

Leaving the city centre behind to follow a ledge above the Lune valley, the canal abruptly turns left and launches out across the river on an embankment leading to engineer John Rennie’s masterpiece – the Lune Aqueduct. We’ve mentioned the series of aqueducts on the canal, but this one outshines all the rest put together, with its five 60ft high arches carrying the canal for 600ft across the wide river.

Another sharp left turn is followed by a meandering length leading to Hest Bank, and a very rare treat for canal boaters – a view of the sea! Well, to be fair, for a lot of the time it’s a view of Morecambe sands, but it is unusual for an inland waterway to run quite so close to the coast.

Bolton-le-Sands village is followed by Carnforth, with its railway station with links to the film ‘Brief Encounter’, the last town before the limit of navigation. For the final few miles, the canal heads inland again, passing rather ominously under two motorway bridges in quick succession carrying the M6 and a spur road, followed by the village of Borwick.

Carnforth Station Heritage Centre

Carnforth Station was made famous by the classic 1945 film Brief Encounter. It’s still a working railway station but it’s also home to a heritage centre with displays recreating the atmosphere of earlier eras, a heritage mini-cinema showing the film, a platform adorned with vintage posters and suitcases, and a bistro and bar.

Carnforth Station was made famous by the classic 1945 film Brief Encounter. It’s still a working railway station but it’s also home to a heritage centre with displays recreating the atmosphere of earlier eras, a heritage mini-cinema showing the film, a platform adorned with vintage posters and suitcases, and a bistro and bar.

Why ominously? Well, as you’ll see when you round the final bend to reach the current limit of navigation at Tewitfield, it was the construction of the M6 motorway which put paid to navigation on the final length of canal from here to Kendal. The canal ends abruptly at a winding-hole (turning point) which is immediately followed by an embankment carrying a main road on the approach to a bridge over the adjacent motorway, and blocking the canal’s route. The canal ends, as it began, rather in the middle of nowhere.

On the final section approaching the canal’s terminus

And while the embankment might not seem too difficult an obstruction to overcome, the flight of eight disused locks on the other side of the road, which the canal used to climb to reach its summit level, are followed by another more serious blockage carrying the M6 itself across the canal at just a few feet above water level.

So sadly, we have to end our journey here, tantalisingly short of the start of the Lake District. Well, actually we don’t. For the long-term, the Lancaster Canal Trust aims to reopen the entire route through to Kendal.

As featured in the June 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the June 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here