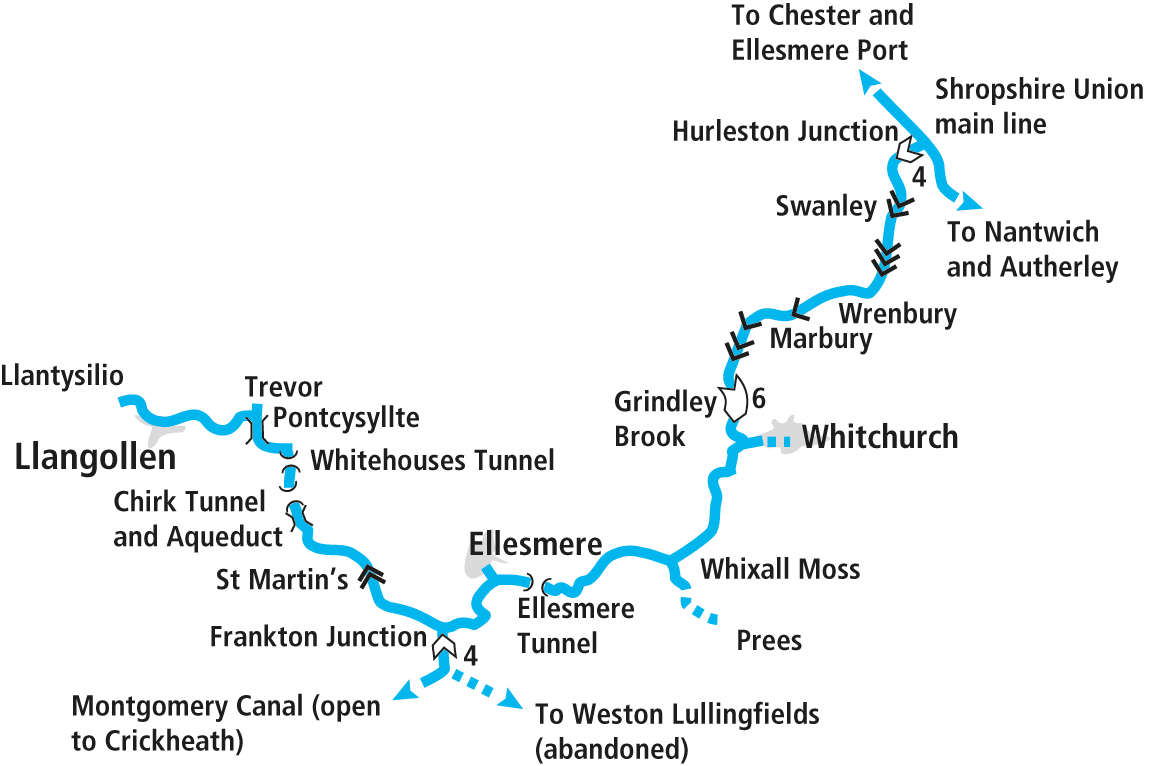

Reaching from Cheshire into the Welsh hills, the Llangollen Canal is a favourite on account of its fabulous border country scenery and its impressive canal engineering – culminating in the iconic Pontcysyllte aqueduct

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

With its glorious Welsh and borderland scenery, spectacular canal engineering, and almost entirely rural route, the Llangollen Canal is one of our most popular holiday waterways – so it’s appropriate that we’re featuring it in this Holiday Special issue of Canal Boat.

But before we go on, a brief word of warning about its popularity. It’s actually such a big favourite among boaters that it does get busy at times – indeed, the locks at New Marton consistently feature in first or second place in the annual ‘Lockage Report’ detailing the busiest on the network. In fact, some would go so far as to suggest that newcomers to the waterways should avoid it and go somewhere quieter – but my suggestion would be to choose a less busy time of year if you can (my first ever boat holiday was on the Llangollen in October, and we had a marvellous week); and if you can’t, then just allow yourself plenty of time to enjoy this fabulous waterway, then if you do end up having to wait for locks you can be chatting to your fellow boaters rather than worrying about getting to the end of your cruise in the available time.

And on the subject of locks, as soon as you make the turn from the Shropshire Union Canal’ main line onto the start of the Llangollen Canal at Hurleston Junction, you’ll meet the Hurleston Flight, the first four of the 21 locks which make up the relatively gentle climb into Wales. Unlike those on the northern ‘Shroppie’, they’re narrow locks – and the Llangollen’s locks (particularly these four at Hurleston) have had a reputation for being particularly narrow, resulting in some boats (particularly historic working craft built to 7ft wide rather than the more usual 6ft 10in for leisure craft constructed in the last 50 years or so) getting wedged in. But following a major rebuilding exercise a few years ago the tightest of the locks at Hurleston is now considerably less tight, and craft shouldn’t have problems.

Look out on the right as you leave the last of the four closely-spaced locks, and you’ll see a spillway channel leading off, usually carrying a fair amount of water away from the canal. This is the feed to Hurleston Reservoir, originally built as a canal water store, but used since the mid-20th Century as part of mid Cheshire’s drinking water supply – and one factor in ensuring the canal’s survival, even though it was legally abandoned by its then owners the London Midland & Scottish Railway in 1944.

That’s not just an interesting quirk of canal history – it’s the origin of a feature of the canal that you’ll become aware of as you approach the next locks, the pair at Swanley which you’ll reach after a couple of miles. The use of the canal as a drinking water supply means that a considerable volume of water passes down it, creating a noticeable flow. It’s not like being on a river, but it’s certainly different from the typical more-or-less static canal, and it’s noticeable in narrow places such as tunnels, bridges, aqueducts and particularly the approaches to locks. The increased flow is carried around the locks by larger-than-usual ‘bywashes’ (overflow channels), which enter the canal just below the bottom gates – and have a tendency to push your boat sideways at the last second, just when you’ve lined it up perfectly for the narrow lock chamber. But with a little practice you’ll get the hang of compensating for it by steering just a little closer to the side that the bywash is on.

Swanley Locks: note the powerful flow from the bywash on the right

Swanley locks are followed by the Baddiley three, as the gentle climb out of the Cheshire Plain and towards the borderlands continues. The canal meanders gently through quiet countryside punctuated by villages including Wrenbury, where you’ll be introduced to the first examples of one of the Llangollen’s characteristic features: lift bridges.

These come in various forms: of the three here, Wrenbury Frith Bridge and Wrenbury Church Bridge feature manually-powered hydraulic operation using a lock windlass; while sandwiched between them is Wrenbury Bridge, which carries a public road and is power operated using a Canal & River Trust ‘Watermate’ key.

There’s a pub beside of Wrenbury Bridge, and shops in the village, so it’s a handy place to stop.

Wrenbury Lift Bridge carries a road and is operated electrically by CRT key

The gentle climb has become even more gentle, with a four-mile level pound leading to four single locks spread out over three miles. There are pubs in Marbury and in the converted lock house at Willeymoor Lock.

A long-disused railway embankment crossing the canal (sadly, the 1960s closures left the canal’s surroundings rather lacking in working railway lines) signals the approach of Grindley Brook, and a little more exercise for the lock crew. Three individual locks are closely followed by a staircase of three: other than in November to March there are usually keepers on duty to help you through, and to regulate boats passing in opposite directions.

The three-lock staircase at Grindley Brook

Then that’s the last we see of locks for almost 20 miles – quite an achievement by the canal’s engineers, given the increasingly hilly countryside that we’ll be entering soon.

Whitchurch is the first town on the canal – or rather, not quite on the canal. It was served by a short branch which was abandoned and filled in for many years, but the Whitchurch Waterway Trust has now restored the first length as moorings. It’s a fine old market town and a useful shopping stop, so tie up either on one of the Trust’s visitor moorings on the arm or on the main canal near the junction, and walk into the town.

The lift bridges return, with several examples in the next few miles, as the canal enters a curious flat landscape at Whixall Moss, a rare example of a raised peat bog. Once exploited as a supply of peat, it’s now preserved as an important habitat for flora and invertebrates, and parts are open to the public as nature reserves. Part way along this length is a junction with another branch, the Prees Arm. It never actually made it to Prees, but it did get as far as Quina Brook, a couple of miles from the junction. Now just the first mile is left, its survival having been ensured first on account of it providing access to clay pits supplying material for repairing the canal lining; more recently the opening of a marina has given this length a new purpose, while the section beyond is another nature reserve. If you explore it by boat or along the towpath, look out for the very unusual slightly skew lift bridge.

Back on the main canal, you might spot a sign indicating that the canal is entering Wales – but in fact it’s back in England again very soon afterwards. The convoluted shape of both the border and the canal means that we don’t get back into Wales again for another 15 miles or so.

Following on from Whixall Moss is another unexpected change of landscape, as the canal enters the little-known ‘Shropshire Lake District’. In the area around Ellesmere (where the largest of them is simply known as ‘The Mere’), there are nine of these attractive wooded lakes, surviving remnants (as is Whixall Moss) of the retreat of glaciation at the end of the last Ice Age. The canal runs alongside two of them, Cole Mere and Blake Mere, before disappearing into Ellesmere Tunnel. The first of three on the canal, it’s equipped with a towpath but too narrow for boats to pass each other underground (however, at only 87 yards long you’re unlikely to have to wait long for it to be clear).

Whixall Moss

Whixall Moss

A rare example of a raised peat bog habitat, Whixall Moss and the adjacent Fenns Moss and Bettisfield Moss are accessible from the towpath via six walking trails of different lengths. The area is home to mammals including water voles and water shrews, rare peatland plants, butterflies, dragonflies and other invertebrates, birds of prey, wading and wetland birds, snakes, and amphibians.

Just a little way beyond comes another junction as (like Whitchurch) Ellesmere’s town centre is reached via a short arm, complete with visitor moorings to tie up and take advantage of its shops and pubs.

Leaving Ellesmere behind there’s a little more of a feeling of heading for the hills, with the canal winding its way through undulating countryside with some glimpses of larger hilltops in the distance.

Another junction at Frankton marks the start of the Montgomery Canal, which would surely have been as popular a canal as the Llangollen, had its 35-mile route reaching deep into the heart of Wales not been abandoned under the same LMS Railway Act of 1944. And without the saving grace of a water supply use to keep it in some semblance of repair, it suffered decades of dereliction, damage and blockage by road improvement schemes.

However, a restoration scheme in progress since 1969 has taken great strides forward, and continues to make progress. Over half of the canal is now restored (albeit much of it in isolated sections), and since the most recent reopening in 2023 it’s now possible to cruise some eight miles and eight locks from the junction at Frankton to Crickheath Wharf. Do note that passage through Frankton Locks needs to be booked in advance with CRT, and the opening hours mean that you won’t be able to go down and back up the canal in one day. But if you stay overnight at Crickheath you’ll be in a good place to explore the next length on foot, see the newly built School House Bridge and the sections of channel under restoration, and look forward to one day cruising right through to Welshpool and beyond towards its original terminus at Newtown.

Returning to Frankton, you might notice as you continue westwards that the bridge numbers, which had been counting upwards from No 1 at Hurleston and reached into the 60s, have for some reason re-started from Bridge 1. This is a quirk of a very complicated history, too much so for us to relate in full in this article, but basically 19th century mergers and takeovers meant that what we now call the Llangollen and Montgomery canals came under the Shropshire Union system (along with the waterway that we still know as the Shropshire Union today). And the Shropshire Union company regarded the Hurleston to Newtown route as one line, and Frankton to Llangollen as a branch off it.

Another three miles of border countryside and glimpses of Welsh hills ahead, and we finally reach our first locks since Grindley Brook. The two New Marton Locks complete the climb, and from now it’s level all the way to Llangollen. But it more than makes up for it in other forms of excitement…

New Marton Locks, the only two in the western 30 miles of the canal

A winding length leads into the Ceiriog Valley, the canal running along a ledge high along the valley side before launching out across it in the 70ft high 10-arch Chirk Aqueduct – and crossing the border into Wales as it does so. Despite being somewhat overshadowed (literally) by the adjacent rather higher railway viaduct, this is a very impressive structure and would be the star attraction of the journey from Hurleston were it not for its big brother which we’ll meet in just a few miles.

An unusual feature of Chirk Aqueduct is that it dives almost directly into Chirk Tunnel, with just a small passing basin between. Like Ellesmere Tunnel it’s wide enough to incorporate a towpath but not wide enough for two boats to pass, but unlike Ellesmere its length at 459 yards means you’re rather more likely to have to wait for it to be clear before you enter. Yet another thing to watch out for is that the constricted channel and the current (remember, this canal is supplying Cheshire’s drinking water) makes it slow going in the westbound direction (and slightly faster eastbound).

A final feature of the tunnel is that it tends to shield the canal from Chirk town so it’s easy to cruise through and miss it, which is a shame as it’s an interesting town with a castle worth visiting.

Chirk Castle

Chirk Castle

Begun in the late 13th Century under King Edward I with the aim of subduing the Welsh, this Mediaeval border castle became a private home 300 years later when it was bought by Sir Thomas Myddelton, and is the last castle of this era still lived in today. Its lavish interiors, rich furniture, paintings and tapestries are open to the public from March to October, as are the award-winning gardens and estate parkland.

The tunnel leads into a very rare slightly industrial length of what has up to now been an almost entirely rural canal, before disappearing underground again into the 191-yard Whitehouses Tunnel. Emerging from the tunnel, the canal turns west to run alongside the Dee Valley, with the odd glimpse ahead of the climax of the entire journey – the spectacular Pontcysyllte Aqueduct.

Leaving Whitehouses Tunnel, the westernmost of the three on the canal

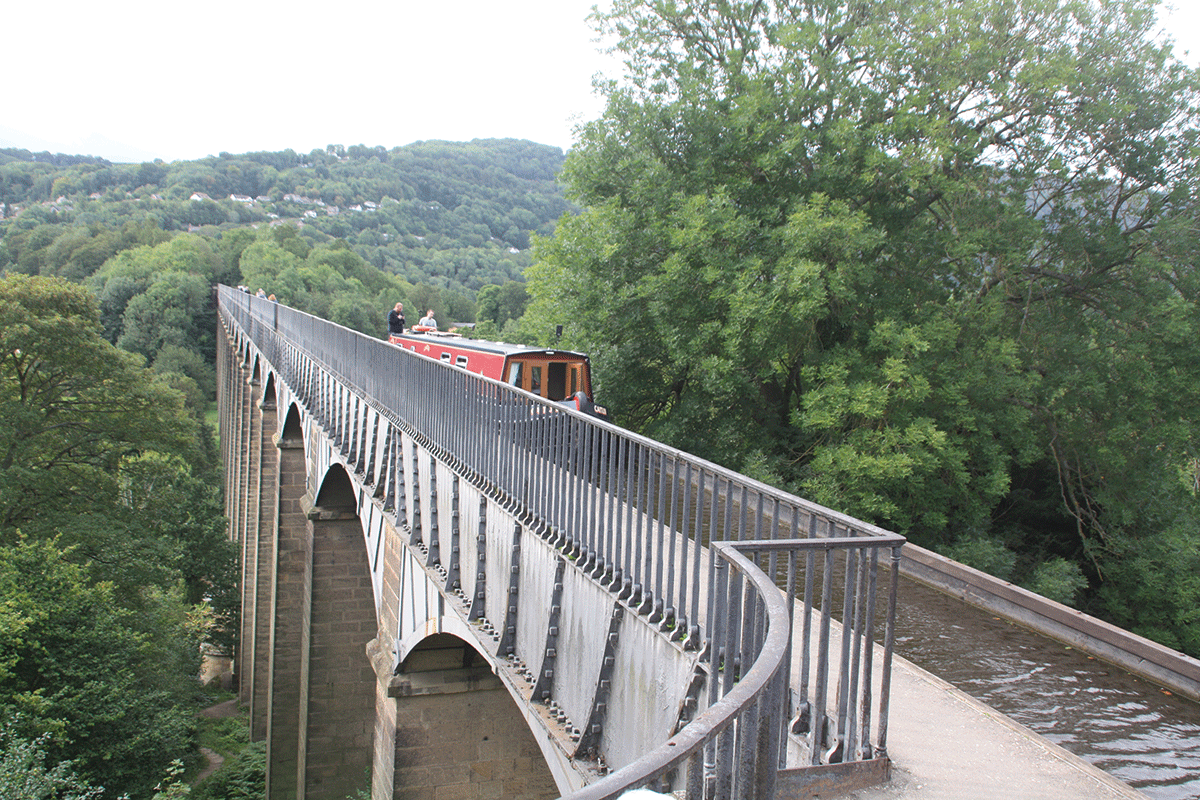

At 1,000ft long and 127ft high, its 19 cast iron spans supported by slender stone pillars put Chirk Aqueduct in the shade. But the bare statistics don’t do justice to the sheer uniqueness of the experience of cruising in mid-air, with a towpath on your right but on the other side just a narrow metal girder barely a foot high between you and the River Dee a very long way below. There really is nothing like it anywhere else on the waterways. This isn’t quite the end, though. The main canal comes to a dead-end in a basin just beyond the aqueduct, but a rather awkward sharp left turn through a narrow bridge leads into the final length, known as the feeder. This was built along the side of the Dee valley for six miles to supply water from the river, but was then made navigable to allow boats to reach Llangollen. Its origins as a non-navigable channel and the constraints of its route along a steep valley side mean that it’s very narrow – there are places where two boats can’t pass, and it’s a good idea to send a crew member ahead on foot. You’ll also find the effect of the current makes for slow progress.

‘Cruising through mid-air’ on the unique Pontcysyllte

But it’s worth it for the cruise up four miles of splendid valley scenery and the arrival at the moorings high above the fine town of Llangollen, well-known for its Eisteddfod, the main base for a popular steam railway, and useful town for shops and pubs. There are visitor moorings on the canal and in a separate basin – for which you will need to pay if you stay overnight.

Even this isn’t actually the end of the canal, but powered craft are requested not to proceed further (and silting means they generally wouldn’t get far, while the narrow channel and lack of a winding hole means all but the shortest wouldn’t be able to turn). However, there are at least three good ways to see this final mile and a half leading to Horseshoe Falls – a semi-circular weir built by Thomas Telford to feed water from the Dee into the head of the feeder.

Firstly, you can walk the towpath; secondly you can take one of the shallow-draught horse-drawn trip-boats which have been operating on this section for very many years; finally you can see it from the windows of a train on the steam railway.

Llangollen Railway

Llangollen Railway

Operating from a restored station in Llangollen town centre within a short walk of the canal, this length of formerly abandoned railway was revived by volunteers and now carries historic steam and vintage diesel trains for ten miles up the scenic upper Dee valley, paralleling the last length of the canal and then continuing through to Corwen.

As featured in the March 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the March 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here