Beginning with a tidal passage in a Fenland landscape, and ending by climbing a rural valley to arrive in the county town of Bedfordshire, a cruise up the Great Ouse is a journey of contrasts.

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

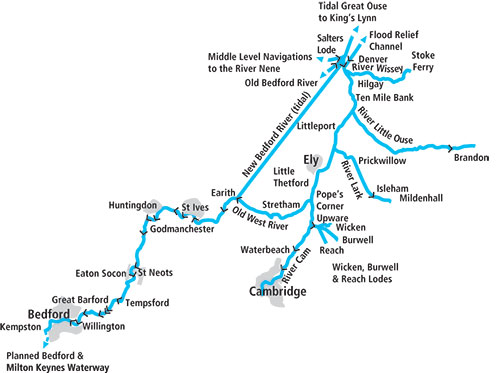

Arriving on the Great Ouse from elsewhere on the waterways network is rather different from most rivers. For starters, it’s quite a way off the beaten track: from the Grand Canal, you’ll need to descend the 17 narrow locks of the Northampton Arm, then cruise almost the entire River Nene from Northampton down to Peterborough, and then navigate through the curious Middle Level fenland Navigations, mostly lying below sea level, before finally entering the Great Ouse at Salter’s Lode Lock.

Arriving on the Great Ouse from elsewhere on the waterways network is rather different from most rivers. For starters, it’s quite a way off the beaten track: from the Grand Canal, you’ll need to descend the 17 narrow locks of the Northampton Arm, then cruise almost the entire River Nene from Northampton down to Peterborough, and then navigate through the curious Middle Level fenland Navigations, mostly lying below sea level, before finally entering the Great Ouse at Salter’s Lode Lock.

Perhaps more importantly, you join the river in its tidal reaches. Admittedly, only for half a mile or so to Denver Sluice, where a lock takes you onto the non-tidal length. But it does mean that you have to not only allow for the current when navigating (requiring plenty of power if you’re turning into the tide at Salters Lode), but also time your journey carefully. The locks can only operate at certain states of tide: typically only one suitable time per day in each direction. The good news is that there are lock keepers at both Salter’s Lode and Denver who will advise you – you should contact them in advance to check the timings.

There’s an added complication if your boat’s longer than about 60ft, as Salters Lode Lock was omitted when locks on the Middle Level were lengthened some 20 years ago. Boats longer than this can still use it if they time their journey for when the tide makes a level, and for a few minutes both sets of gates can be opened at once. Mention this when contacting the lock keeper about your trip – and be aware that on some days it won’t be possible.

On the calm non-tidal reaches above Denver

As you cruise the half-mile from Salter’s Lode to Denver, in between making sure that you keep clear of any mudbanks, look out for a couple of channels heading off on your right: the first leads to the lock gates marking the entrance to the Old Bedford River, the start of a second navigable route across the Middle Level system which has been out of use for 15 years or so since the Environment Agency declared Welches Dam Lock unsafe, and dammed it off. The second channel you’ll see bearing off, just as you approach the lock at Denver Sluice, is the New Bedford River – a long, dead straight, tidal channel heading for Earith – see later.

START EXPLORING

I hope the description of the tidal passage hasn’t put you off visiting the Great Ouse, because it’s really not a difficult trip, and once you’re through into the calm non-tidal waters beyond Denver Sluice there’s over 150 miles of mostly attractive rural river to explore, comprising the Great Ouse itself plus tributaries and connected waterways – which we’ve covered in a separate article on page 54. The first of these is the Great Ouse Relief Channel, a former flood control waterway which branches off on the left just a few yards beyond Denver.

Admittedly you might not class some of the first few miles as “attractive rural river”. It’s not that it isn’t rural, nor is it particularly unattractive, but it isn’t exactly river-like. Like so many Fenland waterways, its course has been changed over the years as part of the historic reclamation for agriculture of what had been bogs and lakes.

The lower Great Ouse hasn’t just been straightened: it was diverted several hundred years ago to follow an entirely new course from Littleport via Denver to King’s Lynn, having previously flowed some way further to the west to enter The Wash near Wisbech. You can read more about these historic changes to the Fenland rivers in our article in Canal Boat February 2022.

Having said that, the first few miles aren’t the stereotypical dead straight fenland waterway running across a flat landscape; the Great Ouse meanders a little as it heads southwards past Ten Mile Bank and Southery. And boaters in need of something more river-like can detour up the River Wissey (see Cruise Guide Extra in February 2023’s Canal Boat). Sticking with the main river, the course straightens and heads southwest with a road on each of its banks, past the village of Brandon Creek (turn left for the next tributary, the Little Ouse) and on to Littleport, a handy town a short walk from the river. An even straighter length accompanied by a railway line leads via the confluence with another tributary, the River Lark, to Ely.

At Pope’s Corner the river narrows down considerably as the Old West River section begins

VISITING ELY

Ely’s attractive waterside is a great place to tie up and visit this fine city with its splendid cathedral set on the higher ground which kept it clear of the fenlands and their floods. It’s just a few miles south from there to Pope’s Corner where the River Cam joins, while the Great Ouse undergoes a sudden transformation.

We’re now joining a section known as the Old West River, a curious name for a river which flows eastwards. This is another reminder of the changes over the centuries. In Mediaeval times this was a relatively small stream flowing westwards to join the Great Ouse, which in those days flowed northwards from Earith to March and Wisbech. Some time later, either as a result of floods or artificial intervention, the flow in the Old West River was reversed, carrying part of the river’s flow eastwards to join the Cam and run north via Ely.

Eventually the route via March dried up and the Ely route became the main course of the Great Ouse, reaching King’s Lynn as described above. However in the 17th century when the New Bedford River was cut, it took most of the river’s flow, the Old West River reverting to a backwater. Today its narrow, twisting and rather remote course is a contrast to the lengths both upstream and downstream of it. Look out for Stretham Old Engine, a restored land drainage pumping station open to the public on certain days.

SOME SURPRISES

Hermitage Lock, the first since Denver, is operated by a keeper (the opening hours vary through the year, and there is a lunchtime closure). It marks the end of the Old West River section and another unexpected change – the short section of river beyond it is tidal. This may seem very odd, given that we left tidal water behind 30 miles ago, but it’s because this is where the Great Ouse meets the New Bedford River, a dead straight tidal channel forming a short cut from here to Denver. (Incidentally it’s navigable as a short cut to Denver, but unless you’re tight for time it really is the sort of waterway that mainly appeals to those who feel the need to navigate absolutely everything that they can!)

An added curiosity is that although at Denver you normally lock uphill from the tidal into non-tidal water, here at Hermitage you do the opposite!

The tidal range here is never more than 2ft 6in and often much less, and really needn’t concern you unless you’re planning to moor up, in which case you need to make allowances for changes of level. I once stopped overnight on a floating pontoon mooring at a pub in Earith (sadly currently shut), and there are EA short-stay moorings just beyond the village.

Incidentally, on the subject of moorings, whilst the EA does provide a number of visitor mooring sites, visiting boaters (especially those who like tying up in quiet, out-of-the-way places) might like to join GOBA, the Great Ouse Boating Association, a useful organisation which represents boaters on the Great Ouse system and provides numerous generally quiet, simple 48-hour mooring sites to its members free of charge.

The tidal length ends at Brownshill Staunch, a guillotine-gated lock and adjacent sluices standing in an empty and slightly bleak landscape. Unlike Hermitage Lock (and unusually for a tidal lock) there is no keeper; its powered gates being boater operated using an EA key. It can take some time, as a result of the delay mechanisms to prevent it being filled or emptied too quickly.

The rather remote Brownshill Staunch, end of the short tidal length past Earith

LEAVING FENLANDS

Leaving Brownshill, the Great Ouse begins another transformation: the Fenlands are being left behind, and the river has reverted to its original course and to a generally more river-like appearance, meandering across its flood-plain with fields and watermeadows running down to the waterside.

St Ives Lock introduces two features which will become familiar. Firstly it is fitted with a guillotine bottom gate (you’ll be relieved to hear that unlike the Nene where some hand-wound gates survive, all those on the Great Ouse are now electric, operated by EA key) but conventional mitre gates at the top; and secondly the lock chamber is an irregular shape, having been widened on one side for part of its length to increase the number of boats that can fit. At busy times it’s common for a mix of cruisers, narrowboats, small craft and the odd widebeam to find themselves sharing.

You’ll spot St Ives’ most unusual historic building ahead of you – the chapel standing on the middle of the partly Mediaeval town bridge. Of just four bridges in the country that share this feature (the others being at Bradford-on-Avon, Rotherham and Wakefield), it’s the only one you can cruise through. The building has also at times been a doctor’s surgery, a toll-house, an inn and even a brothel.

But there’s much more to St Ives, with its attractive riverfront, interesting museum, historic parish church (which had the misfortune to lose its spire to a direct impact from an aeroplane in 1918) and useful shops, pubs and restaurants. The Norris Museum is a small but fascinating free museum tells the story of Huntingdonshire from ancient times onwards, covering social history, personalities, war, archaeology, science and technology, art, costume and transport.

The Fenlands have been forgotten as the river takes a broad sweep around the historic Hemingford Meadow, and passes Hemingford Grey with its fine riverside church and Houghton’s historic mill to reach the neighbouring towns of Huntingdon and Godmanchester. There are moorings for Huntingdon by the 14th century bridge which links the two towns (and which has a slight kink in the middle, owing to an error when building inwards from both ends), while Godmanchester can be accessed from moorings on a dead-end millstream which branches off left above Godmanchester Lock and leads to the attractive old town via the interesting timber-built ‘Chinese Bridge’. Speaking of locks, these have continued at regular intervals, many accompanied by old mills, of which those at Brampton and Eaton Socon survive converted into pub restaurants.

The Mediaeval bridge linking Huntingdon and Godmanchester – with a slight kink in the middle

SIGNIFICANT DATES

Offord Lock displays an assortment of old metal plaques: “This sluice was erected 1834”; “GOCB Reconstructed 1938” and (on the guillotine gate) “Great Ouse River Board 1963”, which provides an opportunity to recall some of the river’s history. Originally made navigable from St Ives up to Bedford in the 17th century, it later suffered from competition from the Grand Union Canal (in combination with road carriage) – but was put back into good repair under new ownership in the early 19th century (hence the 1834 plaque).

It was to no avail, and competition from railways led to almost complete disuse by the late 19th century. Another new owner put it back in order again, but haggles with local authorities over the right to charge tolls led to him finally closing the locks.

But in the meantime pleasure boating had begun on the upper river, and the owner leased the uppermost locks to the River Ouse Locks Committee, which had been formed to reopen the river for pleasure craft. And lower down the river, in the 1930s, the Great Ouse Catchment Board was set up primarily for land drainage, but began rebuilding locks (from St Ives to Eaton Socon) to use as sluices and to enable it to move its workboats – hence the 1938 plaque.

When it resumed work after the Second World War, GOCB had moved away from using workboats so had less incentive to restore locks. But in 1951 the Great Ouse Restoration Society, a voluntary organisation, was founded to campaign, fundraise and carry out volunteer work on rebuilding the rest of the locks. Working with the GOCB’s successor the Great Ouse River Board (hence the third plaque), it succeeded in its objectives with the reopening of the final lock in 1978.

Passing old mill buildings below Eaton Socon Lock

THE RIGHT ROUTE

History lesson over, we’ll continue upstream to reach St Neots, an important riverside market town and a useful place to stop. Incidentally, do watch out for the signs indicating which way to pass around the islands below St Neots Lock – it’s not the obvious route.

Both the East Coast Main Line railway and the A1 trunk road make themselves felt in this area, but beyond Tempsford the river turns westward and follows a quieter route. Look out for the River Ivel joining just below Roxton Lock – this too was once a navigable tributary, but was abandoned in 1876 (see our Cruise Guide Extra on page 54)

Roxton and the following three locks were the final ones to be rebuilt – they no longer had any flood control function (there are large weir / sluice structures alongside all of them) so they have conventional gates. Above Great Barford Lock is the historic Great Barford Bridge, an interesting structure built in stone in the 15th century and widened more recently on one side in brick, but a slightly awkward one to navigate through with its small arches – take it carefully.

An attractive narrow wooded reach leads to Willington and on to Castle Mill Lock, which is a bit of a monster. Not only does it have a rise of around 9ft, but it’s built deep enough to cope with another 6ft or so of flood water. Its cavernous concrete chamber is filled and emptied by ground paddles (or ‘penstocks’ in the local terminology) situated half way along the lock chamber rather than at the head and tail.

Approaching Roxton Lock

TO CONTINUE?

We’re now on the final approach to Bedford, passing Cardington Lock (the narrowest on the river at around 10ft 6in) and the large Priory Marina to reach the outskirts of the town. The final lock, Bedford Lock, is a slightly awkward one too. The river splits into two parallel channels known as the Upper River and the Lower River, and the lock is on a small cut that passes between them, with right angle turns both above and below.

A fine stretch of water runs right through the centre of Bedford, passing under the town’s main road bridge with moorings just beyond on the right hand side which are well situated for exploring the town, its attractions and handy facilities. Do be cautious when approaching and leaving the moorings – I managed to run quite hard aground here on shallows on one occasion.

Passing under the bridge in the centre of Bedford, near journey’s end

This isn’t quite the head of navigation: if your boat fits under the low railway bridges, it’s possible to continue for a couple of miles further, although you may have to contend with overhanging trees, and it isn’t always easy to turn round in longer craft. The exact limit depends on how deep draught your boat is, and how much water is in the river.

It might not always be like this – for over 200 years there have been plans for a continuation by a new waterway connecting to the Grand Union Canal. The current proposals are being championed by the Bedford & Milton Keynes Waterway Trust. Will they do it? Well, the obstacles in the way are considerable, but they’ve already succeeded in getting several structures built (including a main road bridge) to allow for construction of the new link – which is further than any of the previous schemes got. So there’s got to be a good chance!

As featured in the February 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the February 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here