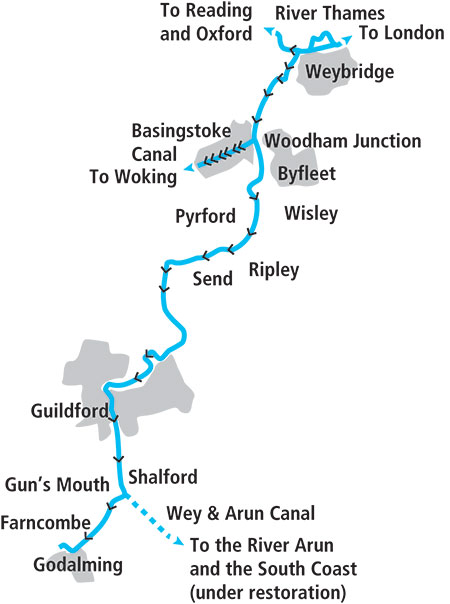

Take a diversion off the busy River Thames to explore the Wey, reaching southwards through quiet countryside to Guildford and Godalming

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

The River Wey is one of our shorter waterways, but it packs a great deal into its 15 miles, not just in terms of attractive scenery and enjoyable cruising, but also quirky navigation features, and a long and interesting history as one of our earlier navigable rivers, as well as one of our last to see regular freight traffic.

The River Wey is one of our shorter waterways, but it packs a great deal into its 15 miles, not just in terms of attractive scenery and enjoyable cruising, but also quirky navigation features, and a long and interesting history as one of our earlier navigable rivers, as well as one of our last to see regular freight traffic.

But hang about, did I say “one of our shorter waterways”? Well, that’s actually not quite right, because technically it’s actually “two of our shorter waterways”. Why? Because one of its historical quirks is that what we think of today as one river was opened as two separate waterways, over 100 years apart.

The first part was the River Wey Navigation, where work began as early as 1651. It was quite an advanced waterway for the day – unlike many river-based waterways which stuck mainly to the natural river, widened, straightened and with the addition of locks and weirs where necessary, its builders forsook the original river channel for most of the way. No less than ten miles of artificial canal sections were interspersed with five miles of river, as the waterway climbed via 12 locks from the River Thames at Shepperton to Guildford.

There it stopped for more than 100 years – and for the first 30 of those years, it was embroiled in litigation and disputes partly as a result of its original Act of Parliament having been granted during the Commonwealth following the Civil War, and being regarded as null and void following the Restoration of the monarchy (not helped by it passing through the King’s lands), while the waterway fell into a poor condition. But eventually matters were settled, trade increased, and by the 1760s, it was felt to be worth extending the Wey for a further four miles and four new locks to Guildford to tap into the timber trade in the surrounding area. Oddly, this extension was built by a separate company (hence my comment above about two waterways) and they remained separate right up to the 1960s.

Although the two parts have now come under a single authority, administration of the river still remains separate from the rest of the national waterways system. Instead of becoming part of either the Canal & River Trust network or the Environment Agency rivers like most waterways, in the 1960s both the original Wey Navigation and the Godalming extension were handed over to the National Trust, which continues to run them.

Waiting for the ‘pound gate’ at Thames Lock to be closed so that the level can be raised to allow the boat into the main lock chamber

You will become aware of this very soon after you leave the Thames as the keeper at Thames Lock, the first on the Wey, will be checking your River Wey licence or issuing you one if you don’t already have one. But before you get there, you will have to choose the right channel amid a maze of weir streams and backwaters that join the Thames below Shepperton Lock – basically, it’s a sharp right turn out of Shepperton Lock, then take the second left of the four channels that it splits into, and a couple of hundred yards of wooded channel will bring you to Thames Lock.

As you reach the lock you’ll encounter one of the Wey’s quirky features. In addition to the normal set of gates at each end of the lock chamber, it has a single third gate some distance further downstream, around a bend. This is known as the ‘pound gate’, and is needed because the depth of water over the cill at the normal bottom gates is very shallow. All boats deeper than about 1ft 9in (the exact figure will depend on the water level in the river) will need to wait above the pound gate while the gate is shut and the water in this length is raised enough to get over the shallow cill and into the main chamber.

But don’t worry, the lock keeper will supervise this – and will introduce you to a few other features of River Wey lock operation. Firstly, the National Trust rules are that both gates should be opened for all boats, even narrow ones which would fit through a single gate. Secondly, the sometimes quite fierce paddles mean that it’s recommended to use ropes both ends to control the boat, especially when ascending. Thirdly, being a river navigation where water supplies are rarely an issue, it’s the convention to leave gates open when leaving a lock. And finally, as some of the paddles are fairly heavy (they lack reduction gearing) the lock keeper can loan you a River Wey windlass with a longer throw than a typical canal lock windlass.

Thus inducted, you’re ready to go it alone at the second lock, which is approached via an attractive half mile of meandering tree-lined river. It’s a somewhat awkward approach in longer craft: you’ll see a bridge ahead, then you’ll start to think (or at least I did on my first trip) that “that bridge looks a bit too low!” before you realise that you won’t need to fit under it as it’s not part of the navigable route at all. Immediately before it there’s a very sharp right turn into a separate bridge for the navigation, which leads straight into the lock.

Coxes Mill, the destination of the river’s last freight, now converted to residential use

Weybridge’s ample shops and pubs are a ten to fifteen-minute walk away from either of these first two locks.

The river is left behind and there now begins a lengthy artificial canal section, which soon leads to a couple more locks. The first, Coxes Lock, is accompanied by an impressive former grain mill building: Coxes Mill was the destination of the last freight traffic on the Wey, arriving from London in horse-drawn barges into the 1960s, and revived for a short time in the early 1980s with motorised craft, before the mill closed down and was converted to its present residential use.

A long straight length leads through New Haw and past the fringes of West Byfleet, where the Basingstoke Canal leads off on the right. Restored from dereliction and reopened to boats in 1991, this provides an attractive 31-mile cul-de-sac leading into the heathlands of Surrey and Hampshire – and will be the subject of a future cruise guide.

The junction is overshadowed by both the noisy M25 motorway viaduct and the main railway from London Waterloo to the South West, but soon these are left behind as the waterway enters open countryside. Pyrford Marina (the only one on the Wey) provides moorings and there are boater facilities plus the popular waterside Anchor pub, while Pyrford Lock continues the climb towards Guildford.

Speaking of locks, look out for the informative notices on all or most of the locks – the National Trust has generally managed to find some historical or technical factoid about each lock, whether it’s the deepest unmanned lock on the Wey, the first built, or marks the start of the longest artificial canal section.

The unusual turf-sided flood lock at Walsham

The plaque at the next lock, Walsham Flood Gates, indicates that it’s the last turf-sided lock on the navigation. Like many early river navigations, the Wey’s locks originally didn’t have chamber walls at all, just sloping grass-covered earth sides, with the only fixed structure being around the upper and lower gates. All of them were rebuilt over the years – I recall New Haw still being partly turf-sided into the 1980s – leaving the Kennet as the only river where they now survive in regular use – with the exception of Walsham. Being a flood lock, it’s generally only needed when the river levels are higher than usual, so you’ll probably find it with both sets of gates open and cruise straight through.

It has a couple of other odd features: firstly, it’s on a slight bend – the top and bottom gates don’t quite line up with each other – and secondly, the paddles use to fill and empty it lack any kind of paddle gear. They are simply lifted up and down using wooden handles on the top of the vertical wooden rods attached to the paddles, and held in position with a peg placed in a hole in the rod. This may be easy enough when (as with a flood lock) the water levels on either side of the gates are unlikely to be more than a few inches. But spare a thought for the barge crews of old, who had to contend with these when they were fitted on all the locks, even the deepest on the river. And to make matters worse, there were no gate walkways to operate them from. The technique, as described in author JB Dashwood’s account of an early pleasure boat journey in 1867 involved sitting astride the gate to “by violent jerks raise it inch by inch” using a 3ft crowbar. On one occasion, Dashwood got the lock worked for him by simply bribing some haymakers in a local pub with beer.

Quiet cruising near Send

Above Walsham, we finally reacquaint ourselves after five miles with the actual River Wey, which has followed its own course all the way from Weybridge Town Lock. An attractive, quiet (especially given that we’re in what you might have thought of as the heart of the Surrey commuter belt) and meandering length takes us via Newark Lock (and the adjacent historic Newark Priory – see below) to Papercourt Lock (watch out for a weir stream entering by the lock tail which can be rather fierce depending on river levels) before another canal section leads to Cartbridge.

Cartbridge is an extension of Send village, forming the first actual canalside settlement for some miles, again remarkable for reputedly densely-populated Surrey. Another flood lock, Worsfold Flood Gates, features a conventional masonry lock chamber but with the same very basic paddles as Walsham – but once again boaters needn’t usually concern themselves with operating it, as it’s generally left open at both ends.

Newark Priory – The former priory is on private land and not publicly accessible, but do look out for the substantial remains visible to your right as you head upstream towards Newark Lock. The priory dates back at least to the 12th Century, but fell into ruins following King Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries

The last few miles into Guildford feature more stretches of natural river, including some very attractive lengths as well as a few sharp bends. Look out for another distinctive historic feature: rollers mounted vertically alongside the towpath on the inside of the tightest bends, for the tow-ropes of horse-drawn barges to run around.

The approach to Guildford remains rural for some way as its outskirts keep clear of the floodplain, but then the river threads its way between industrial and business premises before reaching the National Trust’s River Wey base at Dapdune Wharf (see below). The length through the town is a pleasant urban waterway with convenient moorings for Guildford’s shops, pubs and other attractions.

Dapdune Wharf is the National Trust’s base for maintaining the River Wey Navigation, but it’s also a visitor centre telling the story of the navigations and the people who lived and worked on them, and home to two surviving wooden Wey barges that carried freight on the river

Beyond the town bridge the original 17th century Wey Navigation ends and we are now at the 18th century Godalming Navigation – as a plaque by Millmead Lock reminds us.

Cruising past Shalford

There’s no real change, though, as the waterway leaves the town via a winding length (watch out for sandbanks on the bends) running in a steep-sided valley through the Surrey hills to reach Shalford. Beware of the low Broadfield Bridge (you may well need to remove anything on the roof of your boat), and look out for a channel branching off to the left just beyond. This is the start of the Wey & Arun Canal, a long-abandoned through route to the south coast now under restoration by the Wey & Arun Canal Trust.

Journey’s End at the wharf and turning point in Godalming

Catteshall Lock is the last on the river (or the first, according to its plaque, which is clearly looking at things from the opposite direction), and is something of a boating centre with adjacent boatyard and hireboat operation. The final length to Godalming is accompanied on the west side by the Lammas Lands, riverside meadows whose name commemorates their traditional use from Lammas (1 August) to Lady Day (25 March) for common grazing, and the rest of the year to grow grass for hay.

There are moorings on the approach to the town, which is well worth visiting and a widening for a sharp right-hand bend provides ample room for the largest craft to turn, beyond which navigation comes to an end for all but the smallest craft at the town bridge.

This is not only the end of our journey, but the southernmost point reachable on the national navigable network. At least until the Wey & Arun Canal Trust’s plans come to fruition…

As featured in the March 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the March 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here