Follow the Avon Navigation as it winds its way past glorious countryside and historic towns, from Tewkesbury with its Mediaeval abbey to Shakespeare’s Stratford

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

Given that the name ‘Avon’ originates in a Celtic word meaning ‘river’ – the modern Welsh word for ‘river’ is ‘afon’ – it’s hardly surprising that Britain has several rivers of that name, including at least three which have been navigable at some time, and another one sometimes mentioned in connection with canals. So to clear up any confusion we’ll first briefly mention the three that we aren’t covering in this cruise guide…

Firstly, there’s the Bristol Avon, navigable from Bath via Bristol to Avonmouth; this is the one that gives the Kennet & Avon Canal the first part of its name.

Secondly, there’s the Hampshire Avon, which rises in the Vale of Pewsey (and therefore coincidentally crosses the Kennet & Avon Canal when it’s still a small stream) and flows southwards through Salisbury. From there to the South Coast it too was once navigable, after a fashion, but fell out of use after no more than 30 years. Salisbury seems to have been rather ill-starred when it comes to navigable links – an attempt to link it to Southampton by canal was spectacularly unsuccessful, the almost-complete canal going bankrupt after a very few years.

Thirdly, there’s the Scottish Avon, flowing near Linlithgow to reach the Firth of Forth near Grangemouth, and chiefly notable to us on account of the spectacular aqueduct carrying the Union Canal 86ft above it on 12 arches.

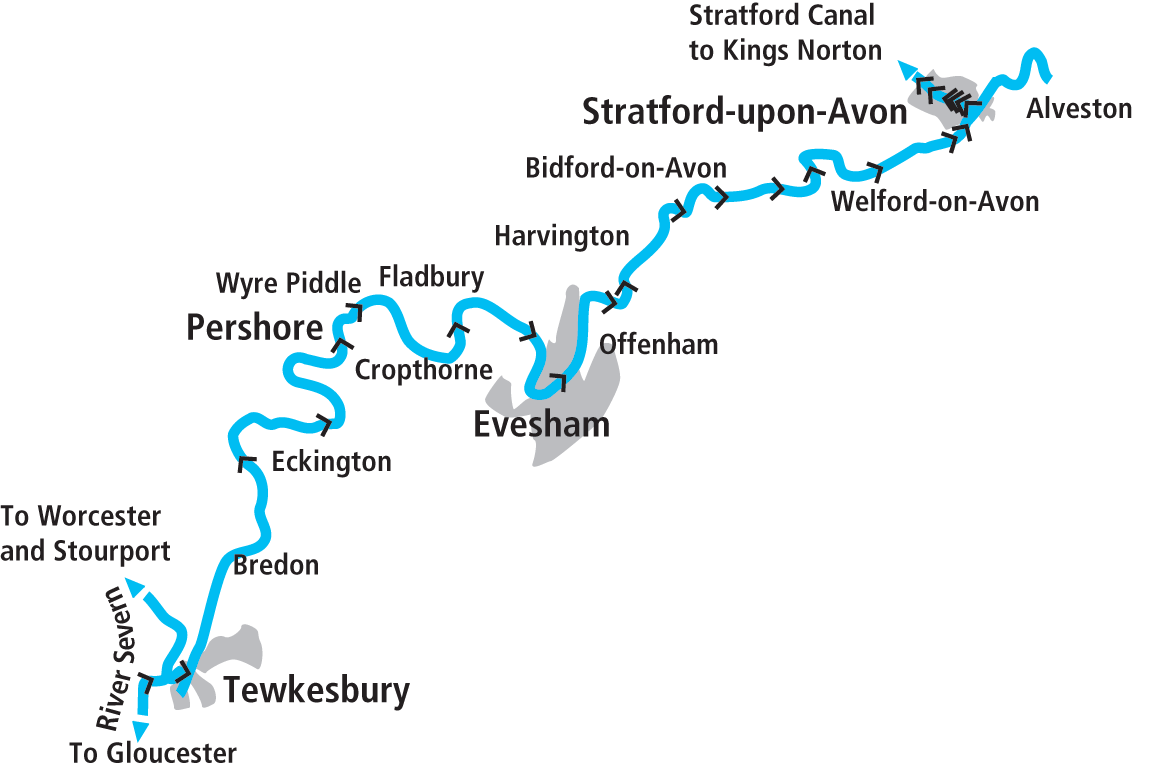

And that brings us to the river that we’re actually dealing with in this issue: The Warwickshire Avon, also known as Shakespeare’s Avon, rising in the East Midlands near Welford (as in the Welford Arm of the Grand Union Leicester Line), but not becoming fully navigable until just above Stratford-upon-Avon, from where it can be cruised through to where it meets the Severn at Tewkesbury.

Welford on Avon

Welford on Avon

Welford is a delight to lovers of traditional English villages, with its historic centre (a conservation area) containing a large number of thatched houses, including what’s believed to be the original ‘chocolate box’ cottage – plus three pubs and what’s said to be England’s tallest maypole

It’s a river with a long and interesting history, opened as early as the 17th Century, it’s an interesting and attractive waterway today, and it’s a crucial link in the popular and varied Avon Ring circuit of waterways which also takes in the Stratford-upon-Avon Canal plus parts of the Worcester & Birmingham Canal and the River Severn.

We’re going to follow it upstream from the Severn to Stratford – and the first of its interesting features is the entry from the River Severn at Tewkesbury.

Arriving from the River Severn

The Avon through Tewkesbury splits into two channels – the Mill Avon and the Old Avon – which join the Severn at different points, well over a mile apart, on opposite sides of the Severn’s Upper Lode Lock. The navigable channel is the Old Avon, which branches off upstream of Upper Lode and about half a mile downstream of Thomas Telford’s Mythe Bridge. It’s an easy enough entrance to spot, but if you’re approaching from the north (the Worcester direction), do make sure not to cut the corner as there’s a spit of silt extending out into the river from the junction.

A short length of channel is followed by a dog-leg to the left and right which leads to Avon Lock. Note that on the left bend there are visitor moorings: this is important because unlike all the other locks on the river, Avon Lock is keeper-operated. So it’s handy if you arrive after the keeper has gone off duty, given that you’re on a river navigation where unlike most canals, casual mooring to the towpath isn’t generally available. It also provides an overnight stop for boats passing on the Severn – there is a temporary overnight Avon licence available (currently £5) for this.

“Avon licence?” I hear you ask. Yes, this is a waterway that isn’t part of either the Canal & River Trust network or the Environment Agency’s river navigations. It’s run by the Avon Navigation Trust, an independent charity and successor body to the groups that restored the river from dereliction and it has its own licensing system. You can buy an annual licence but most visiting boaters will either use a 24 or 48 hour ‘excursion’ licence for a short out-and-back trip returning to the same point or a 7, 14 or 30 day ‘through’ licence valid for a through trip between Tewkesbury and Stratford. They’re available online or from the lock keeper at Avon Lock. Having acquired their licence and been worked through Avon Lock by the keeper, most visiting boaters will turn sharp left to continue upstream, but a few might first turn sharp right instead: this is the Mill Avon, the other branch of the river which was dug in the 12th century to serve the Abbey Mills, and it’s navigable for half a mile as a dead-end to where the former weir prevents further progress.

Returning to Avon Lock and continuing upriver, the navigation passes under King John’s Bridge (take care, visibility through the bridge is not good) before heading out into the countryside – but it would be a shame not to first tie up and visit the town. Tewkesbury is famous for its fine Norman abbey, but it’s also worth exploring its ancient narrow streets and alleyways, museums and old buildings – including a few good pubs.

Upstream from Tewkesbury

Leaving the town behind, the Avon meanders through a wide floodplain, passing Twining and Bredon villages. Strensham marks the next lock and like all the rest on the river it is boater-operated (although at popular times you will often find volunteers from ANT on hand to help at locks). Eckington Bridge is one of several ancient structures crossing the river, its six stone arches dating from the 16th century.

Some idea of how indirect the river’s course is can be gained from the fact that it’s just as easy to walk into Eckington village from Strensham Lock or Eckington Bridge, which are two miles apart. The same is true of Birlingham, which the river takes three miles to almost encircle as it follows the first part of a huge S-bend. Meanwhile Bredon Hill, rising to over 1000ft, is visible from the river for a number of miles, and can be climbed on foot from Nafford lock for a panoramic view of the surrounding countryside.

Passing Pershore’s ancient bridge

Pershore to Evesham

The exaggerated windings of the Avon continue (watch out for the 180-degreee Swan’s Neck bend) as it passes Great Comberton and nears Pershore, the first town since Tewkesbury. Watch out for the old Mediaeval Pershore bridge and the adjacent structure carrying today’s road traffic on the approach to the town (their arches don’t align very well with each other) and the curious ground paddle at Pershore Lock which is situated alongside the lock and must be opened before the top gate paddles. There are moorings above the lock to visit the town with its market, shops, pubs and old buildings.

The village of Wyre Piddle is notable not just for those wishing to snigger at its name, but for those in need of a waterside pub or interested in the unusual Wyre Lock. This is diamond-shaped, and the last survivor of several odd-shaped locks which also once included a circular lock. It’s also quite short – a full-length 71ft 6in Grand Union ex-working boat will pass through (I’ve done it) but it’s a tight squeeze.

The gentle climb continues, with locks at Fladbury and Chadbury as the Avon approaches its next town, Evesham. One again the river makes a large loop around the town, with visitor moorings at various points including below Workman Bridge and on either side of the lock.

Evesham Lock, where the Lower Avon used to end and the Upper Avon began

A change of style

Evesham Lock used to mark the change between the Lower Avon and the Upper Avon, but for quite some years a single navigation authority has been responsible for the entire river, so there’s no longer any distinction for purposes of licensing. You will, however, still notice a change when you arrive at the next lock, Offenham Lock. As explained in more detail in our Cruise Guide Extra, whereas the Lower Avon retains its original locks, the Upper Avon restoration involved completely new structures – and as such, they were built in an unashamedly modern style by restoration mastermind David Hutchings and his team, using steel piled lock chambers. Offenham boasts a curious lockside structure also dating from the restoration: a circular lock-keeper’s hut with steps to the roof, to which its intended that the keeper could retreat in the event of floods!

Harvington Lock follows closely, and it’s even newer having been replaced in the 1980s on a new site (the lock built during the restoration having been rather awkwardly sited as it was the only land available at the time) and built to generous dimensions.

Steeper banks and a narrower valley characterise the next reaches as the Avon passes Cleeve Prior and Marlcliff to reach Bidford-on-Avon, where another Mediaeval bridge, built by monks from Alcester, spans the river. But it’s the rather more recent history of the bridge that’s of interest to boaters: during the restoration it was a side arch towards the south bank of the river which proved more practicable to make navigable, rather than what might seem the obvious higher central arch. Look out for the arrows indicating which span to use.

Leaving Barton Lock

Into Shakespeare country

Bidford provides shops and pubs, as well as an excuse to mention an apocyphal tale that William Shakespeare wrote a rhyme awarding it the epithet ‘Drunken Bidford’ after he’d been involved in a drinking competition in one of its pubs. (I can’t help imagining the landlord pointing to the door and saying “You’re bard!”)

Barton, Bidford Grange and Welford locks continue the rather steeper climb – or perhaps I should call them E&H Billington, Pilgrim and WA Cadbury locks. Most of the new locks built during the restoration of the Upper Avon were given names commemorating individual benefactors or organisations that had contributed to the funding of the restoration, although these days the guide books often use geographical names instead.

The final miles of river approaching Stratford are accompanied by quiet countryside, while the unnavigable River Stour (another river name that’s rather overused, with several of that name around the country) joins from the south. A recently opened new marina followed by glimpses of the tall spire of Stratford’s parish church mark the approach to the town.

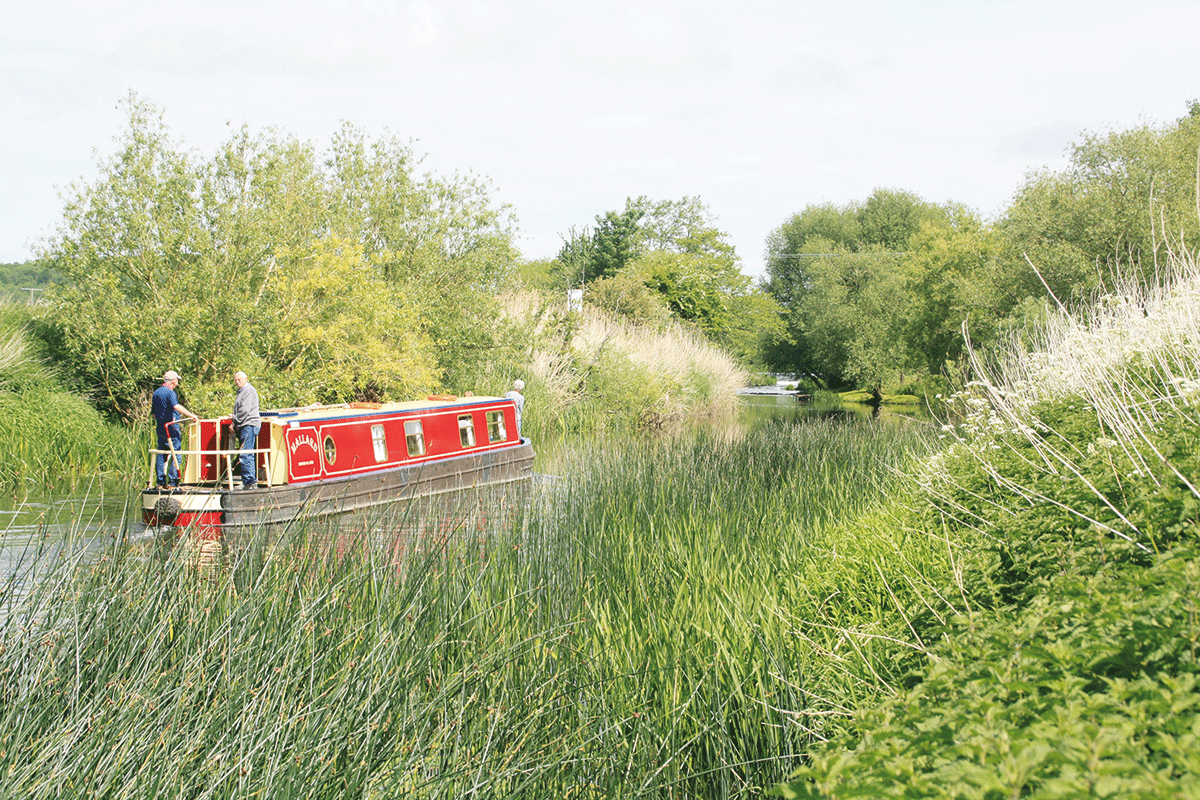

Cruising on a typically rural length of the upper river near Bidford

The approach to Stratford

Weir Brake Lock is closely followed by Colin P Witter (or Stratford) Lock – which is notable for being spanned by a series of steel bracing structures, which have an interesting story. When David Hutchings was planning the restoration, it wasn’t at all certain that restoration of Weir Brake Lock would be permitted by the authorities at all: it might be necessary to abolish it, build a deep lock in Stratford, and to lower the length of river between the two sites. The new Stratford Lock was therefore built an extra 5ft deep to allow for this possibility, with the steel bracing added as a precaution to ensure its stability given the less-than-solid riverside ground that it was built in. In the event, permission to build Weir Brake Lock was belatedly given, so Stratford Lock had been built 5ft deeper than necessary, and with unnecessarily heavy-to-operate bottom gates. So some years later it was rebuilt with its depth reduced by 5ft. This meant that the steel bracers were no longer needed, but by now they’d become such a distinctive feature that it seemed a shame to remove them. It’s not the prettiest lock on the system (a Stratford councillor is said to have once described it as “Mr Hutchings’ monstrous erection in the park”) but there’s nothing quite like it.

Passing the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford

The lock leads into the final splendid reach of river with a public park on the right, and the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre and the Parish Church on the left. Watch out for the unusual hand-operated passenger ferry, hauling itself and its cargo of tourists across the river on a wire (which is lowered to allow boats to pass), followed by the famous Royal Shakespeare Theatre on the left, and immediately afterwards the entrance lock of the Stratford Canal.

Royal Shakespeare Theatre

Royal Shakespeare Theatre

See a play at the world-famous venue, or book a guided tour taking in parts of the famous theatre which are not normally open to the public. While you’re in Stratford, visit some of the other features of the Shakespeare Trail including the Bard’s birthplace and Ann Hathaway’s Cottage

Most boaters will turn left to head up the canal, but as at the Tewkesbury end of the river there’s an optional dead-end excursion. It’s possible to carry on under two bridges (once the main road, the other built to carry an early horse-drawn railway) and continue upstream to the head of navigation on the river. As for where that limit actually is, it depends on how deep your boat is and how much water there is in the river. Take it carefully (and don’t blame us if you get stuck aground!) and be aware that (depending on your boat’s length) there might not be much space to turn around. Ultimately in the unlikely event that you haven’t already run out of water, the weir at Alveston puts a stop to further progress.

Tempting though the thought is of one day being able to continue beyond there, right through to Warwick and the Grand Union Canal, as mentioned in our Cruise Guide Extra on the following pages such proposals have never made it off the drawing board. So for now it’s a case of stopping before you run out of water and returning downstream to enjoy all the famous attractions of Stratford-upon-Avon.

BOATERS’ NOTES:

Mooring: unlike most canals, casual mooring on the towpath isn’t generally possible (in fact there isn’t a towpath for much of the way). Please make best use of the visitor mooring space available and be prepared to ‘breast up’ alongside other boats.

Locks: boaters are requested to use ropes fore and aft when locking, and to leave lock gates open after them.

Water levels: this is a river based waterway so high levels and strong currents can occur after heavy rain. Make allowance for this, and if in doubt be prepared to moor up somewhere safe and wait for levels to fall.

Bridges: the navigation arch isn’t always the obvious central span. Look out for arrows indicating the correct arch to take.

As featured in the June 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the June 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here