The hills and steeply sloping route made it a challenge for its engineers to build, but left us with a fascinating and attractive route – not to mention rather a lot of locks…

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

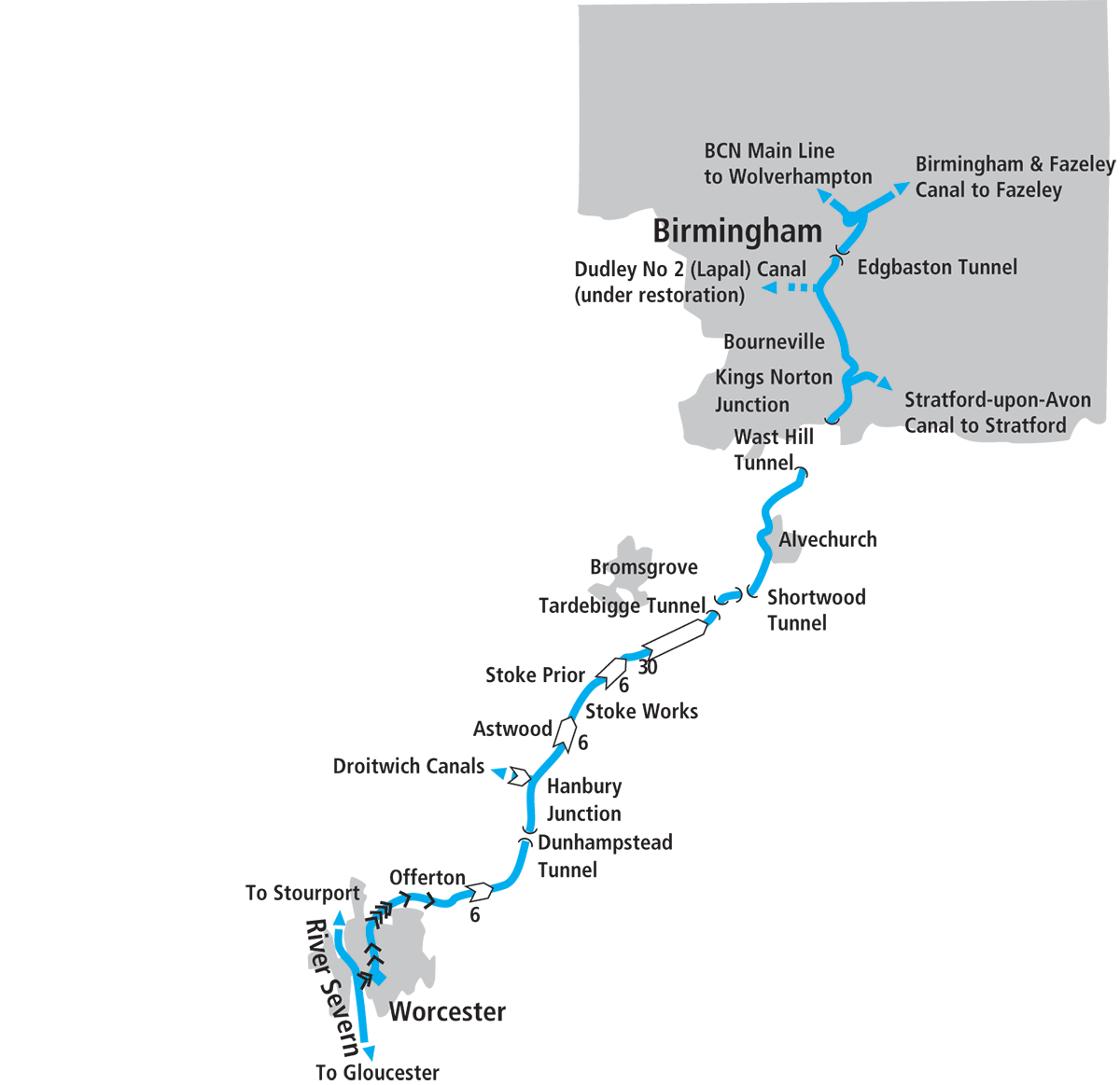

When the Worcester & Birmingham Canal was first proposed in its current form in 1789, it had plenty going for it. Its promoters reckoned it would not only shave 30 miles off the distance compared to the earlier route via Wolverhampton the Staffs & Worcs Canal and the River Severn, and 15 miles shorter than the still uncompleted route via the Dudley and Stourbridge canals, but it would cut the tolls charged for the journey by more than half. It would also avoid the then unreliable navigation on the Severn between Stourport and Worcester, where locks had yet to be built. Surely it couldn’t fail.

A challenging route

But on the other hand, it faced some considerable challenges – whose legacy provides much of the interest and attraction of the canal to todays boaters. Some of these challenges were physical: high ground to be negotiated near the Birmingham end, then a steep descent to the Severn. Others were political: the very fact that it would be so much more direct, led to opposition from the companies operating the older routes that it would bypass.

You can see the result of one of these political issues at the very start of our journey, at Gas Street Basin in the heart of Birmingham, where the Worcester & Birmingham Canal meets end-to-end with the main line of the Birmingham Canal Navigations (BCN). The basin’s alternative name of Worcester Bar refers to a physical barrier which separated the waters of the two canals as a result of the BCN company’s opposition to its new neighbour. The BCN joined forces with the Staffs & Worcs company to defeat the first attempt at an Act of Parliament to enable the new route to Worcester to be built; they failed to defeat a second attempt the following year, but got some onerous conditions written into the Act. The worst of these stipulated that the new canal should not come closer than 7ft from the BCN. So a physical barrier or ‘bar’ would separate the two waterways, and all through trade would have to be transhipped across it from one boat to another.

Still, work could start on building the canal. As a local poet put it:

“Come now, begin delving, the Bill is obtain’d,

The contest was hard, but a conquest was gain’d,

Let no time be lost, and to get business done,

Set thousands to work, that work down the sun…”

Despite these exhortations it took 20 years of hard work (and more than double the original funding estimate) before the canal was ready to open in 1815, by which time common sense had prevailed and the Worcester Bar had been bypassed by a shallow water-regulating stop-lock. But as you pass through the now gateless former lock chamber you can still see the bar alongside on your left, running across the basin, with boats moored either side of it.

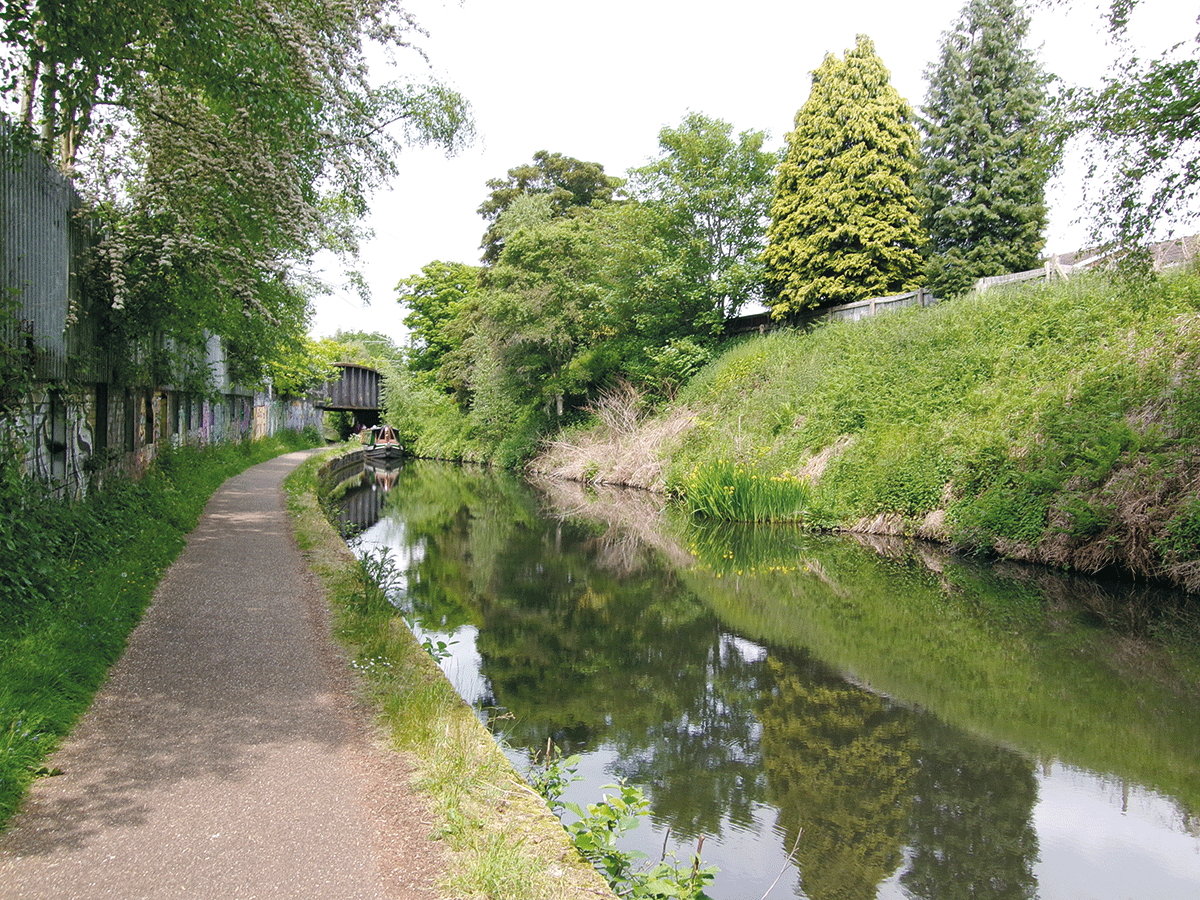

The route out of Birmingham is via a series of cuttings shared with the railway line

The route out of Birmingham

As the modern developments which now surround the basin are left behind and the canal takes a right-angle turn to the right, it’s the physical challenges of building it which become more evident. The canal enters the first of a long series of rocky sandstone cuttings as it cuts through the high ground on the way out of the city centre. The main Birmingham to Bristol railway line keeps it company (clearly the canal-builders had found a good route, so the railway-builders just followed it) but otherwise it’s a secluded, rather private way out of the city – and one of my favourite such journeys. And is it just me, or do other boaters wave to the people on the passing trains?

A short tunnel at Edgbaston is the first of five on the canal. In my book, that makes it the most on any individual British canal (i.e. excluding amalgamations like the BCN or the Grand Union system), representing another of the challenges to the canal builders. Unusually, it’s equipped with a towpath, which controversially was widened a few years ago for the benefit of walkers and cyclists who use it as a commuter route, at the expense of it no longer being wide enough for two narrowboats to pass each other underground – although given its modest length that’s not a huge issue.

Passing Birmingham University, the canal briefly forsakes the long cuttings for a short embankment including the recently built Ariel Aqueduct. That’s not a misprint for ‘aerial’ (although it is quite high); it’s a commemoration of the Ariel company which made motorcycles nearby. This is shortly followed by the former Selly Oak Junction. Here the Dudley No 2 Canal joined: from here it ran via the 3795-yard Lapal Tunnel, Coombeswood, Gosty Hill and Netherton to join the Dudley Canal’s original line at Park Head near Dudley. A useful link which bypassed the BCN Main Line, it suffered subsidence problems affecting the long tunnel, eventually closing the canal as a through route in 1917. Lapal Canal Trust is working to reopen it, and while full restoration is an ambitious aim, the initial target of opening up the first section through Selly Oak Park as a dead end with visitor moorings is well within the Trust’s sights. You can already see a tunnel-like opening underneath a supermarket development which will form the canal’s new entrance, and on the opposite side of the Worcester & Birmingham Canal a new mooring and turning basin has been created which will in future enable craft to access the constricted turn into the restored canal.

Another verse of the poem mentioned earlier continues…

“With pearmains and pippins ’twill gladden the throng

Full loaded the boats to see floating along;

And fruit that is fine, and hops for our ale,

Like Wednesbury pit-coal, will always find sale”

Although I can’t help thinking the reference to coal was probably more representative of the canal’s regular traffic than the picturesque descriptions of Worcestershire’s agricultural produce, one rather more unusual cargo that the poet wouldn’t have known to mention was chocolate. But we’re now approaching Bourneville, where Cadbury’s factory was a regular user of the canal for many years, with boats bringing in the basic chocolate ‘crumb’ from another canalside factory at Knighton on the Shropshire Union Canal, as well as carrying milk and other requirements.

Today its main attraction to boaters is the Cadbury World family attraction (see inset) but you’ll find other things to interest in Bournville, which was created as a garden village for Cadbury employees, including Selly Manor Museum. What you won’t find, at least not within the boundaries of the Cadbury estate, is any pubs. George Cadbury would not have wanted it.

Cadbury World

Cadbury World

Ten minutes’ walk from the canal at Bridge 77 by Bournville Station, this family attraction situated at the Cadbury’s factory tells the story of chocolate and the Cadbury’s business in 14 zones including various static sets, animatronics, video presentations, multi-sensory cinema, interactive activities and staff demonstrations.

The railway leaves to pursue a separate course, as the canal continues through cuttings to reach King’s Norton, where the Stratford-upon-Avon Canal branches off. A fine former canal company house faces the junction, and has recently been restored following a serious arson attack several years ago.

Into the countryside

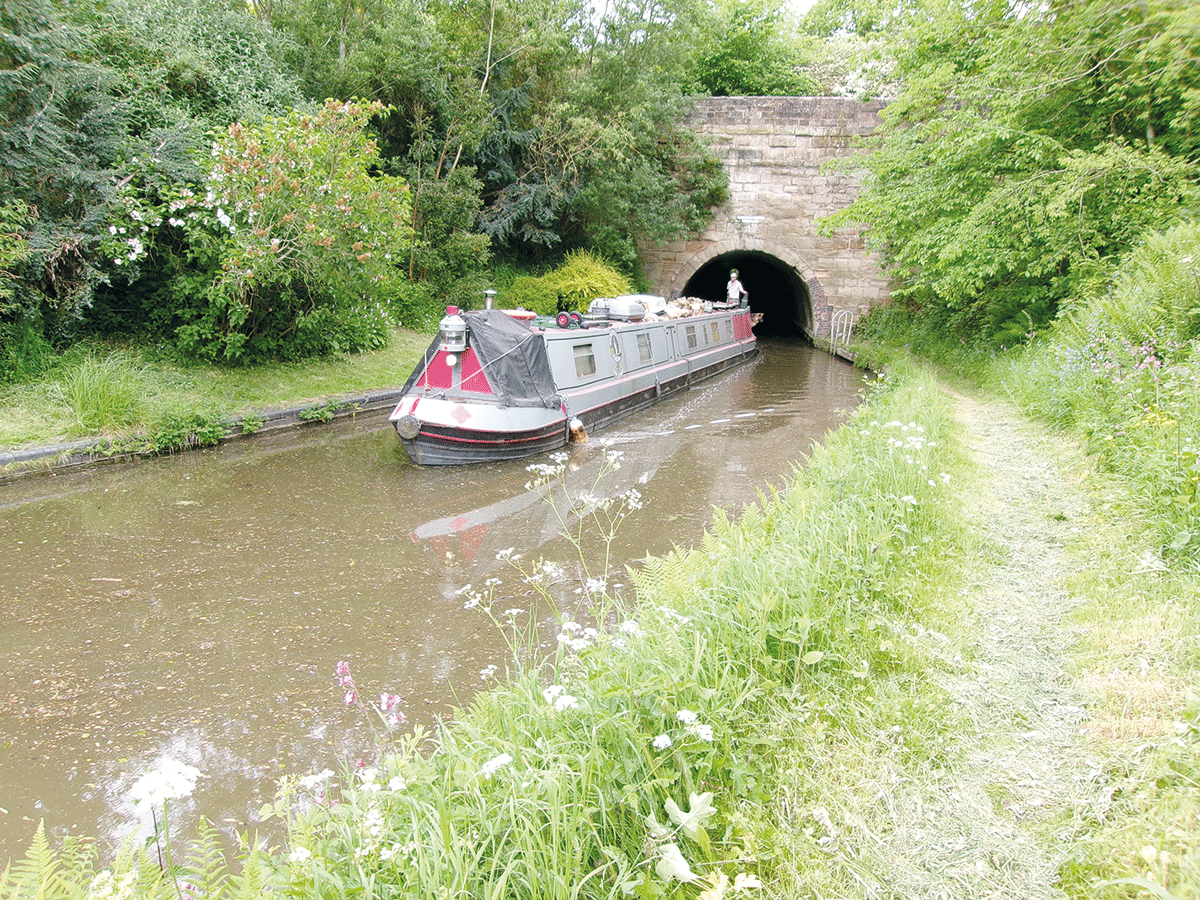

Up to now we’ve been travelling through Birmingham’s southern suburbs (although the canal’s secluded course means this hasn’t always been obvious), but over the next few miles this changes completely. A long straight cutting leads towards Wast Hill Tunnel, the longest on the canal at 2726 yards, and like all the tunnels from here on it is wide enough for two boats to pass each other, but lacks a towpath. There’s no dedicated tunnel-top horse path, so walkers will need to find their way via local roads to the far portal, leaving the last of the built up area behind them on their way. For boaters, the tunnel itself marks the change: you enter it in built-up King’s Norton, but you leave it to find yourself in fine countryside.

The canal has changed too: the long, straightish cuttings have been replaced by a more meandering length as the canal follows the contours past Hopwood and Alvechurch. On the right are the two Bittell Reservoirs which provide its water supply; unusually the canal runs along a wide embankment that forms the dam of the lower reservoir.

The well-known boating centre at Alvechurch provides the first such services since the start of our cruise, and the canal then plunges underground into Shortwood Tunnel, followed after barely a mile by Tardebigge Tunnel, as the canal’s engineers did what was necessary to stick to the same level for the entire first half of the canal.

Leaving Tardebigge Tunnel

The end of the long level

At Tardebigge, everything changes again. The long level extending all the way back to Birmingham (and most of the way from there to Wolverhampton, not to mention the first ten miles of the Stratford Canal) comes to an abrupt end, as we meet the next challenge overcome by the canal’s engineers.

We’re at 453 feet above sea level; the Severn at Worcester is 422 feet below us – and just 15 miles away. Faced with the challenge of overcoming this steep change in level, the engineers looked around for alternatives to the large number of locks (and the water supply necessary to operate them) that it would take. John Woodhouse, an engineer working on the Grand Junction Canal, had invented a boat lift, and the canal company agreed with him to split the cost of building an experimental one at the start of the descent at Tardebigge. If successful, they hoped to use a series of these lifts plus just 12 locks to get to Worcester.

It was a vertical lift (rather than an inclined plane) with a 12ft rise and fall, and it carried a boat in a wooden tank or ‘caisson’, counterbalanced by a platform weighted with a large number of bricks, the two being connected by eight chains running over a series of giant cast iron pulley wheels. Two men would operate it by winding on windlasses, and there were vertical gates connecting it to the canal at each end.

Repeated testing, in which it was reported that a boat could pass through in two and a quarter minutes, and that two men could work 110 boats through it in a 12-hour shift (they must have been exhausted!) showed that the design worked. But still the company had their doubts. They called in engineer John Rennie (who was something of a ‘Mr Fixit’, brought in by various canal companies for his advice), and his view was that although it worked it was “too complex, too delicate in its parts, and requires much more attention and careful management” than it could expect to receive in day-to-day use, and the result would be frequent closures for repairs.

So having established that sufficient water supplies could be found, the Company reverted to building conventional locks – 58 of them altogether, in one of the biggest concentrations of locks away from the north of England.

You may notice a couple of things as you enter Tardebigge Top Lock. Firstly, it’s a narrow lock: although early plans had been for a widebeam canal (and all the tunnels and bridges so far, except for a couple of later railway bridges, were built to 14ft width), water supply considerations led to the 7ft narrowboat width being chosen. Secondly, it’s very deep: about 12ft rise and fall. That’s said to be because it replaced the experimental lift with its 12ft rise. And thirdly, just above the lock on the non-towpath side is a plaque recording that in 1946, waterways revival pioneers Tom Rolt and Robert Aickman met here on Rolt’s boat ‘Cressy’. This meeting led to the founding of the Inland Waterways Association, and is credited as a key event in kick-starting the movement to save and revive the canals. Oh, and a second plaque added more recently records that it was actually 1945 rather than 1946!

A rest at last: the pub between Tardebigge and Stoke locks

A steep descent

You might not have much time to look at such interesting glimpses into waterways history for the next few hours, as the Tardebigge flight winds onwards and downwards for 30 locks. The meandering route means you never get the grand (and possibly a little daunting) view like at Hatton or Caen Hill, but although they aren’t hard work they do just seem to go on for ever. Even when you reach the bottom (with a welcome waterside pub) there’s no let-up, as there’s no real break before the Stoke flight. Another six locks and you finally do get a rest, and a chance to look at your surroundings…

Although the canal’s route is largely rural, the area around Stoke Prior was once quite an industrial area, with a rock-salt mine and salt works providing plenty of trade for the canal, and some industry remains. An interpretation board records the arrival of a rather more recent industry, when the well-known Harris’s paintbrush factory moved here in the 1930s. An unexpected result of this was that a woodland originally planted with hardwood trees to provide the materials for brush handles, became surplus to requirements with the development of modern materials, and is now a canalside nature reserve.

There’s little more than a mile’s rest before the locks begin again with another flight of six at Astwood, but rather more spread out in rolling countryside as the descent finally begins to ease. And from Astwood Bottom Lock, crews finally get a proper rest with a five-mile pound between there and the next lock. This includes Hanbury Wharf, another busy boating centre and also the turning for the Droitwich Junction Canal.

After Dunhampstead Tunnel, the last of the five, the canal passes Tibberton village before descending yet another flight of six locks at Offerton. And although there are glimpses of the Malvern Hills in the distance, we’re now into the approach to Worcester. Business parks and housing estates line parts of the canal, but there are plenty sports grounds and playing fields to provide some greenery, and much of the canal is tree-lined.

Quiet (if rather overgrown) length near Hanbury

The approach to Worcester

The last eight narrow locks are strung out over several miles as the canal descends into Worcester. Passing just east of the city centre, the canal runs right alongside the Commandery (see below) at Sidbury Lock, before the final length leading to Diglis Basins. These two basins, once the city’s inland port where cargoes could be transhipped between River Severn trows (sailing barges) and canal narrowboats, now form Diglis Marina with boating facilities available. There are also visitor moorings, and this is a good place to tie up and explore Worcester’s attractions including the cathedral and the Royal Worcester Porcelain Museum.

The Commandery, Worcester

The Commandery, Worcester

Dating back to Mediaeval days, the Commandery building has at various times served as a monastic hospital, a luxurious family home, a Royalist Civil War headquarters, a college for the blind and a print works. It is now a museum with different rooms dedicated to different eras of its history, but with an emphasis on its role in the Civil War, when Charles II was defeated at the Battle of Worcester before escaping to France.

Going back to our 18th century poet for one final time, he predicted that:

“So much does the rage for Canals seem to grow

That vessels accustom’d to Bristol to go

Will soon be departing Sabrina’s fair tide,

For shallows and shoals sailors wish to avoid”

But in this he was wide of the mark. Plans to continue the canal on down from Worcester to Bristol to bypass the tricky River Severn came to nothing; instead, locks and weirs built on the river reduced the “shallows and shoals”, making it a more reliable navigation. So from Diglis Basins we descend the final two locks into the river; and being built to take barges from the river they’re rather wider at around 18ft, although they’re little longer than the narrow locks we’ve encountered so far. They’re also supervised by a keeper, and closed overnight – see the CRT website for current operating hours.

The bottom lock opens straight into the river: left for Tewkesbury, the Avon and Gloucester; right for Stourport and the Staffs & Worcs Canal. Either way, you’ll get a rest from those locks at last!

As featured in the August 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the August 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here