After a lot of behind-the-scenes planning and politics, the Friends of the Cromford Canal’s plan to reopen the Beggarlee length of the canal leading north from the Erewash Canal at Langley Mill is finally getting underway, as Martin Ludgate found out when he joined the volunteers there…

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

If you had happened to be driving along the A610 Langley Mill Bypass road in the East Midlands in late summer 2023, and chanced to notice a few people in high-visibility clothing using building site machinery to manoeuvre some large lengths of concrete pipe and associated fittings into trenches in a piece of land alongside the road, I doubt if you’d have given them a second glance. They’d have looked like they were probably putting in the land drainage works ready to build a housing estate or industrial site.

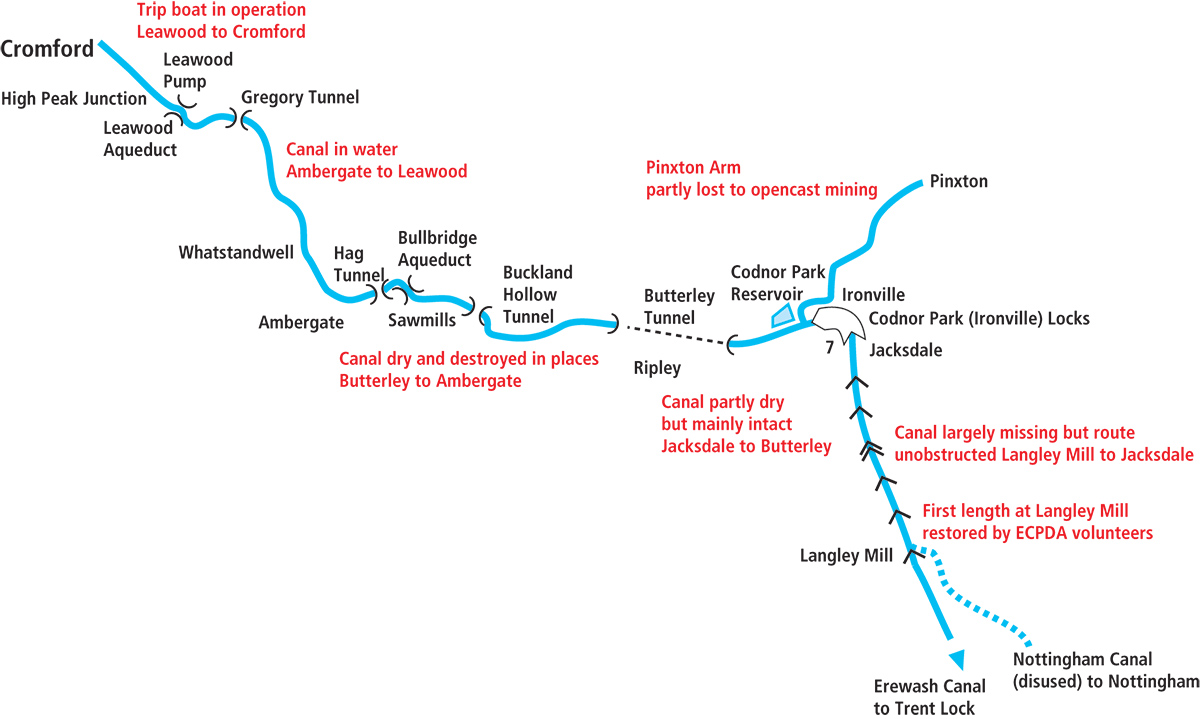

You probably wouldn’t have thought of the possibility that they were volunteers working on a canal restoration project. After all, they didn’t exactly conform to the typical image of what canal volunteers do: things like clearing vegetation from canal beds, repairing decayed brickwork on old lock chamber walls or bridge parapets, reinstating towpaths and so on. But the Friends of the Cromford Canal’s Beggarlee project isn’t a typical canal restoration – as I found out first-hand as a member of that team of volunteers on two working parties totalling nine days’ work this summer. But first, to explain what we were doing, it helps to go back to the later history of the Cromford Canal which once ran from a junction with the Erewash Canal at Langley Mill via Ironville and Ambergate to Cromford; and in particular to what happened to the southern parts of its route after it closed to navigation in stages between 1900 and 1962.

Background to the Beggarlee Project

While the northern sections of the canal remained largely untouched after abandonment, the same sadly couldn’t be said for some of the middle and southern sections – including the first length leading north from Langley Mill.

The very first few yards, including the first lock, were actually restored over half a century ago. It’s what boaters generally think of as the northernmost section of the Erewash Canal at Langley Mill, and it was restored by the Erewash Canal Preservation and Development Association’s volunteers to provide a terminus for the canal at Great Northern Basin, the original Erewash terminus basin having been filled in. And over the years since then, ECPDA has extended the basin so that there are now several hundred yards of canal above Langley Bridge Lock, including moorings and a boatyard. But then it comes to an abrupt end at Beggarlee.

Where the canal used to continue northwards up the Erewash valley towards Ironville, the A610 Langley Mill Bypass curves westward and crosses the canal. Completed in the 1980s, during a hiatus between the ending of the original Cromford Canal Society’s early restoration efforts (following practical problems with flood water overtopping a newly restored section, and disagreements within the Society) and the Friends of the Cromford Canal (FCC) picking up the baton in 2002, the road made no provision for future canal reopening. Its embankment simply blocked the route.

Putting in a new bridge, either by temporarily closing the road or by thrust-boring through the embankment, would be expensive beyond FCC’s means and disruptive to road traffic – but fortunately a much easier and cheaper alternative exists. Close to where the road crosses the canal’s route, it also crosses a former railway siding which connected a colliery to the Midland main line. This was still in use in the 1980s, so a bridge was built to take the road over the railway line, but the mine shut soon afterwards leaving the bridge unused – and available for the canal restorers to reuse.

Rather less fortunately, the old railway bridge is at completely the wrong angle and level for the canal. But ‘beggars can’t be choosers’ (especially at Beggarlee!) so FCC have come up with a cunning plan for a new route for the canal to fit through the bridge. From the current limit of navigation at the end of Langley Mill Basin it will climb through a new two-lock staircase (replacing two original locks whose remains are in completely the wrong place to be used by the new route). It will then turn very sharply (tighter than a right angle) to the right (involving widening the channel to make room for boats to turn) to pass through the former railway bridge. Immediately afterwards there will be a similarly tight and wide left-hand turn, followed by a length of channel heading northwards alongside the road embankment to rejoin the original canal route at Stoney Lane, after about 1km of new channel construction altogether.

Oh, and just one further engineering complication: where the canal will pass through the former railway bridge, there was concern about whether the existing bridge foundations would support the weight of the canal channel, and if not, what would need to be done to strengthen them. So instead, this section of new canal is to be built as an ‘aqueduct’: it won’t look like one, but it will function like one, being built as a concrete channel whose entire weight is supported from its ends by abutments which will be completely independent of the road bridge.

That’s the engineering issues dealt with. But then there were the ‘political’ issues. Planning permission had to be obtained – which it was in 2022. But at the same time, discussions had to be held with all the relevant bodies, not helped by the fact that the A610 forms the county boundary. So there were two county councils, two local authorities, two wildlife trusts and so on, plus the Canal and River Trust, the Environment Agency, and more. All the necessary meetings and permission dragged on, to the point that there was a danger that the planning permission would lapse before work had started – and FCC would have to start all over again with the application!

Work begins at Beggarlee

Laying a pipe culvert underneath what will be the canal channel

So in early summer a call went out for a small team of experienced volunteers to make a start on the work. And the very first job that needed doing before starting to build the new canal channel was to sort out various land drains which crossed the site as open ditches, and would have to be transferred to culverts buried deep enough for the canal to pass above them. Hence why I found myself one morning in mid-July with a group of like-minded folk from FCC and Waterway Recovery Group (The Inland Waterways Association’s national waterways volunteering wing), watching a series of lorries dropping off a large quantity of concrete pipe, plastic pipe, concrete manhole chamber sections, sand, gravel, cement and other building materials, and wondering how on earth we were going to use it all.

But with the whole scheme planned by FCC’s experts, and with the benefit of a WRG leader who’s a civil engineering project manager in his day job, by four days later we had installed a large manhole, connected it up to one of the land drains as it emerged from under the A610 embankment, and begun its continuation in a pipe buried deep under the site of the new canal. And we’d made a start on digging a trench ready to do the same with a second land drain.

This was enough to satisfy the planners that work was under way, but we needed to move the project on further. So several weeks later we returned to the site with a larger team, representing both WRG and the independent southern-based KESCRG mobile canal volunteer group. In the meantime, the FCC volunteers had completed laying the first culvert, and our main job was the second one – of which the principal task was casting a concrete chamber (including constructing all the temporary formwork and scaffolding to support it) to link together the original culvert and the new section. I won’t bore you with what is a not terribly waterways related construction job, but suffice it to say that the main concrete pour (with concrete mixed on site, barrowed and tipped by our volunteers) coincided with the hottest day of the year….

Exploring the route: Langley Mill to Ironville

While all this was going on, I took the opportunity to explore some of the rest of the canal on foot, to see what other challenges FCC face – and that’s something you can do if you’re in the area, as pretty much the entire route is walkable, starting just the far side of the A610 from where we were working.

The easiest way to get there is to take Cromford Road north from Langley Mill, continue onto Plumptre Road, which becomes a dirt track called Stoney Lane, passes under the A610, and bears right. It crosses the River Erewash (actually not much more than a stream), and as it begins to climb the valley side, two footpaths lead off on the left. This is where the initial phase of the restoration will end (a new winding hole will allow boats to turn) and at some point in the future a new bridge will be needed to carry the lane.

Take the first of the two footpaths, and you’ll find yourself walking along what was once the towpath – and with a little imagination I could picture the damp strip of vegetation alongside having once been a canal.

Passing Aldercarr Flash Nature Reserve, the path crosses the River Erewash on a footbridge, and from here on things get rather trickier: there is no sign of a channel or of the two locks which once continued the climb towards Cromford, and the footpath is just a route through the meadows by the river. This is the result of the area being opencast coal mined after the canal shut, and a completely new channel would be needed if it were to be restored.

But persevere, because after a mile or so the canal reappears as a recognisable feature, with the towpath on the right. There are remains of bridges where railway sidings once crossed it, some concrete channel walling, and then a bridge (nicely restored by a local community group) which carries the towpath over the start of the former Portland Basin Arm which served local coal mines via mineral railways. But it’s not obvious where the next two locks were, and to be honest it still seems a rather distant prospect for canal reopening.

Ironville locks are still impressive even in their derelict state

All that changes as the canal reaches the seven-lock Ironville flight. These solidly-built stone locks are still impressive despite the lack of gates and some 80 years’ disuse, as they climb boldly towards Ironville, interspersed with surviving bridges. FCC have already carried out initial work on some of the locks, and restoration looks eminently achievable – all except for the top lock, which sadly was removed as part of a flood prevention scheme around the 1980s which involved deepening a length of canal to create an emergency water channel. You can tell that the levels have changed, because a fine stone junction bridge, which carried the towpath over the entrance to the canal’s Pinxton Arm, now stands at some height above the channel.

Beyond the junction the canal reaches Codnor Park Reservoir, which once supplied the canal and is still kept in water and popular with anglers. Unusually, the wide earth dam retaining the water also carried the canal’s Pinxton Arm northwards, while the main line continued along the south side of the lake.

FCC would like to restore the Arm, much of which is filled in but still walkable with some surviving bridges. While a section was lost relatively recently to opencast mining, there were lengthy negotiations regarding remediation work which will hopefully eventually see the canal channel reinstated through the site.

Back on the main line, the canal is now on its summit level (it was quite an engineering achievement maintaining this level all the way to Cromford), and after another mile it reaches Butterley Tunnel, the longest of no fewer than four on the canal.

Butterley to Ambergate: a tricky section

At 2,966 yards long this was one of the canal’s major engineering works, and it boasted an unusual feature. An underground wharf – from photographs it looks rather like a London tube station, with a widened length of tunnel and a ‘platform’ alongside the channel – enabled coal and other cargoes to be transferred between boats and tunnels connecting to the Butterley Ironworks and mine workings.

A rather less welcome feature of the canal is that it suffered from mining subsidence which caused problems and eventually resulted in its closure in 1900, cutting the canal in two (although some local trade continued on the isolated length for many years) and making restoration a more difficult and expensive prospect.

You’ll need to take a diversion via local roads over the top of the hill to the other end of the tunnel – but if you’ve got plenty of time, you can take in a visit to the Midland Railway Centre with its heritage steam railway plus narrow gauge and miniature lines.

Back on the towpath, you’ll see that this middle section of the canal will have some challenges for the restorers, too, but you’ll also see some surviving features and signs of restoration work. From the tunnel portal (right under the A38; the tunnel was extended slightly by a culvert added when this part of the road was built) the canal heads west, past a blockage where the A610 embankment crosses, to a better preserved length. This is followed by a filled-in section (although the footpath survives), but then at Buckland Hollow not only does the next short tunnel survive, but you can walk through it (it starts from the car park of the curiously-named Excavator pub).

WRG volunteers restoring the Sawmills Narrows a few years ago

Another better-preserved section includes a structure that’s seen some restoration work: the Sawmills Narrows. This is, as its name suggests, a narrowing of the channel to just over a boat’s width. Its function was as a place for boats to stop while a toll-keeper measured their depth in the water to calculate the weight of cargo that they were carrying, and therefore the tonnage toll to be paid. Its stone walls have seen rebuilding work by FCC and WRG volunteers.

This length ends at another structure which presents the restorers with something of a headache. Bullbridge Aqueduct was actually a series of four aqueducts crossing a main road, the Midland Main Line railway, the River Amber, and a smaller road: the first two of these have been demolished, and the planned electrification of the railway using overhead wires adds another complication.

The rest of the aqueduct and approach embankment remain intact, but soon another missing section lost to industrial use means that walkers must divert along nearby footpaths, including a flight of 94 steps! In among all this is Hag Tunnel, the third on the canal.

The restored northern length

On the attractive restored northern length of the canal

You will probably by now be thoroughly depressed at the ill-treatment meted-out to the canal since closure, and the poor prospects for restoration. But continue, because the best is to come. The diversion ends, the footpath returns to the towpath and stays with it all the way to Cromford. This is the section where the original restoration scheme concentrated its efforts in the 1970s and early 1980s, and since then it’s been owned by Derbyshire Council and maintained as a nature reserve – and to prove its credentials, it’s the last place I saw a water vole!

The five and a half miles are entirely in water, the towpath is in good condition, and it follows a superb scenic route along the side of the Derwent valley. Notable waterways features include the impressive Lea Wood Aqueduct (with adjacent restored steam pumping station which topped up the canal from the river); Gregory Tunnel (the fourth and last on the route); an unusual aqueduct over a railway; and the former interchange with the fascinating Cromford and High Peak Tramway, where a small museum tells the story of this very early line which once crossed the Peak District to link to the Peak Forest Canal at Whaley Bridge.

For the last section from the aqueduct to Cromford Wharf, where the canal served Sir Richard Arkwright’s mills (now part of a World Heritage Site), FCC runs boat trips on historic boat Birdswood, sometimes powered and sometimes horse-drawn.

It’s a splendid display of what a restored canal could be like, and although there would need to be a lot of serious engineering work to re-connect it through to Langley Mill (not to mention careful negotiations with nature conservation interests), it does make the efforts back at Beggarlee seem a whole lot more worthwhile.

Back to Beggarlee

And speaking of Beggarlee, having ducked out to explore some of the rest of the route on foot, I was back on site for the last day of the second work party. And by the end of it, the job of laying the pipe culverts under for both of the drainage channels and creating the concrete structures to link them to the existing culverts under the A610 had been largely completed.

I will no doubt be back to help them on the next stage as they create the new canal channel, with its zigzag bends under the A610 bridge, and link it to the existing Erewash terminus at Langley Mill via a new pair of staircase locks. Exciting times lie ahead – with the prospect of a new length of canal for visiting boats to cruise in the not-too-distant future, and the longer-term lure of one day reaching the Derwent Valley and Cromford.

As featured in the November 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the November 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here