Faced with tricky obstacles to restoration and a difficult funding situation, the Manchester Bolton & Bury Canal Society have turned to commercial property developers for support, as Martin Ludgate reports.

What do you do when your plan to restore a derelict canal faces major challenges such as missing aqueducts, demolished road bridges, buildings constructed on the route, and unrepaired breaches? Unlike the early days of canal restoration, you can’t just set up a team of volunteers and plug away at it from one end to the other, repairing structures until the job’s done – because many of the jobs are going to be beyond the limits of the most capable volunteers. But it would be a shame to give up on the idea of eventually reopening the route, when you’ve got other attractive lengths of unobstructed canal that will be much easier to open.

What do you do when your plan to restore a derelict canal faces major challenges such as missing aqueducts, demolished road bridges, buildings constructed on the route, and unrepaired breaches? Unlike the early days of canal restoration, you can’t just set up a team of volunteers and plug away at it from one end to the other, repairing structures until the job’s done – because many of the jobs are going to be beyond the limits of the most capable volunteers. But it would be a shame to give up on the idea of eventually reopening the route, when you’ve got other attractive lengths of unobstructed canal that will be much easier to open.

As many canal restoration projects have found out, a good way of proceeding is for your volunteers to tackle the ‘easier’ bits as a way of demonstrating how feasible and worthwhile the restoration would be. At the same time, you use this to help you to make a good case as you apply for funding grants from bodies such as the National Lottery Heritage Fund and development agencies to pay for the trickier bits. It’s a good approach that’s worked well in the past on the trans-Pennine canals, and more recently on the Montgomery and the Cotswold Canals.

A challenge to find the money

But the sort of cash that would be needed to make good progress on the major challenges facing a group like the Manchester Bolton & Bury Canal Society, who have undertaken a tricky restoration, seems to now be in short supply. This project arrived on the scene too late for the Millennium Fund which paid the lion’s share of the Rochdale and Huddersfield restoration costs. Although listed by the then British Waterways as one of its ‘Tranche Two’ projects which would pick up the baton (and the funding) and be completed in the following years, the economic downturn of 2008 put paid to that. The European, national and regional development funds which have helped many restorations are no longer available; the type of new construction work needed isn’t what heritage funders might class as ‘historical’; we’re between rounds of Government ‘Shared Prosperity’ and ‘Levelling Up’ funding.

Could building developments fund the restoration?

But what the MB&B does have is the potential for commercial developments at various sites along its length – and these can help to fund the restoration. This can be a somewhat controversial approach to reopening a waterway. Some might say that if the cost of reopening a canal is that it will have modern housing and commercial developments along its length, then it would be better to leave it derelict. But what if it’s restricted to key locations where there are challenges to be overcome, with no obvious other way forward?

Flashback to 2008 when the canal was being re-created at Middlewood

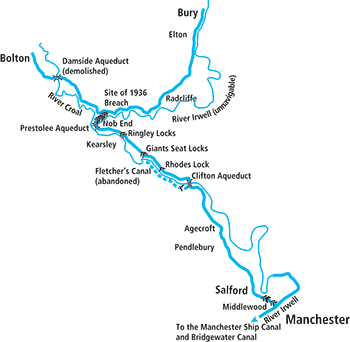

The first of the developments which are helping to get this tricky restoration moving forward was planned quite a number of years ago at Middlewood, at the very start of the canal at the Salford end (despite its name, the canal begins in Salford, on the opposite bank of the River Irwell from Manchester).

Here the canal left the Irwell and climbed a flight of locks (the exact number and site changed over the years as a result of railway development) before passing under a main railway line and heading northwest out of the city centre. But by the time the Manchester Bolton & Bury Canal Society began campaigning to restore the route in the late 1980s, it had long since been filled in, and the new Inner Relief Road running across the bottom of the flight meant that the canal couldn’t be reinstated at its original level.

An opportunity in Salford

However, the formerly industrial surroundings had been earmarked for a new development, and thanks to money put in by property developers Valley & Vale (admittedly also with Regional Development Agency, European and local authority contributions), a £6m package paid to reopen the first short length of canal. This involved building a tunnel under the Inner Relief Road then a brand new double-depth lock (the third deepest on the network, after the deep locks at Bath on the Kennet & Avon and Sowerby Bridge on the Rochdale) to replace the original first two locks and return the canal to its original level. Next, the third lock would be restored, and the canal beyond reinstated (including removal of 80,000 tonnes of material) with new mooring basins, to end at the site of the (infilled) bridge under the main railway line.

The scheme specified that the canal would be built first, before the surrounding developments, and it’s just as well that it did – because with the 2008 economic downturn, the developers went out of business, leaving a restored canal surrounded by some roughly cleared ex-industrial land.

However, another 15 years on, the planned waterside developments are belatedly taking shape under a new developer. Already new homes face the canal on the west side above the locks; more are under construction on the east side; there are further plans for the rest of the site, the attraction of the canalside site belatedly justifying the investment in restoring it.

Looking further north

We’ve started at the beginning of the canal because that’s where the major investment in restoring it has begun – but it’s also a logical place to start our look at the canal, following it north to Bolton and Bury. You can do the same on foot for most of the way – the towpath survives (or has been reinstated) as a public footpath, and for much of the route (even where the canal has been filled in) you can follow the long lines of massive coping stones which formed the edge of the channel – that’s what gave me the idea for the title of this piece! The Canal Society publishes a Towpath Guide which is very helpful for exploring on foot.

The very first section through Salford is one part that you can’t follow on foot – it disappears under the railway, before emerging into the site of the next urban redevelopment scheme. This will protect the line of the canal as a ‘linear park’ through the site; it would be good if it could actually pay to re-water the canal, but it’s an indication of how tight the Canal & River Trust’s finances are that even though it’s a partner in the H2O Urban partnership that’s building the development, the cost makes it too “tricky” (in the words of Chief Executive Richard Parry) to make any promises.

The canal route continues, infilled but with no major obstructions, as it runs alongside the railway past Salford Crescent Station and the university. The following mile of route is occupied by light industries, construction materials and recycling yards, all of which would need to move to allow the canal to be restored, until it emerges on the approach to Agecroft.

From here onwards the channel survives in good condition, its east bank lined by those huge coping stones, and the towpath a popular footpath and cycleway. A small aqueduct which once carried the canal over a narrow lane has been demolished, but otherwise it’s unobstructed as far as Clifton, where it takes a sharp right turn to cross the Irwell on a solid three-arch aqueduct.

The solidly built Clifton Aqueduct over the River Irwell

A tricky length

Beyond the aqueduct the canal took a sharp left, but the channel has been filled in through a former sewage works sludge lagoon site, then the M60 motorway crosses with no bridge, although there are possibilities for dealing with both of these – and meanwhile the footpath continues alongside the river. The next length past Giants Seat won’t be easy to restore either, as a sewage works and an access road have blocked it, while canal bridges have been demolished. However, at Ringley it all changes, with the upper of the pair of locks still recognisable and marking the start of an attractive length, in water and with views across the valley.

Attractive watered section above Ringley

A ‘honeypot’ site

This continues to Prestolee where it leads in to what should one day be the canal’s real ‘honeypot’ site, thanks to its situation in the Irwell Valley and the concentration of canal features. An impressive four-arch aqueduct carries the canal high above the Irwell, then it turns sharp right to climb the six Nob End Locks. These are monumentally built from large stone bocks as two staircases of three locks each – the upper set largely intact; the lower missing a fair amount of stonework. At the top, the Meccano Bridge (a novelty bridge built a few years ago, exactly as its name implies – see picture) leads to a junction: sharp left for Bolton; ahead for Bury.

Taking the left turn first, the Bolton Arm starts well with a mile or so of broad, clear channel as far as Hall Lane. But that’s as far as it’s likely to get for some time, as three aqueducts (including the largest on the canal at Damside) have all been demolished, and the final length into Bolton has mostly disappeared under road widening, limiting prospects for restoration.

Dramatic flight of six staircase locks at Nob End

A disaster – and a solution

Returning to Nob End and taking the other fork, one might be tempted to say the same about the Bury Arm. Within a few yards of the junction the channel narrows down to nothing, and the towpath runs alongside a retaining wall against the steep valley side on the left. Meanwhile on the right, the ground falls away steeply to the River Irwell over 100ft below. This is the site of the breach of 1936, when the canal bank suddenly and dramatically collapsed into the valley below, taking two boats with it.

It was never repaired, and marked the end of the canal apart from a small amount of very local trade. One might also think that it would mark the end of the canal restoration – but this is where our second residential development scheme is providing a way forward.

I mentioned earlier that this could be a controversial approach to canal restoration, and that’s been the case here. Housing developers Watson Homes planned to redevelop the site of Cream’s Mill, a former canalside papermill; however, they believed that the business case didn’t stack up without them also developing two pieces of adjacent land. This was refused planning permission by the local authority on grounds of inappropriate development on green belt land, but on appeal the decision was overturned by the Inspector.

One of the main reasons for the reversal was that the developers have committed to reinstating the canal past the breach site as part of the work. So one of the most difficult obstacles to restoration will be eliminated without any public money – and with initial works already under way, it should be in water during 2025.

This will link the existing Nob End to Hall Lane length with the section beyond the breach, which is already in water and with no obstructions (and with a whole series of surviving bridges, and some fine views across the valley) as far as Radcliffe.

Nob End to Radcliffe is an attractive and well preserved length, with a number of surviving bridges

On to Bury?

Water Street Bridge in Radcliffe has been demolished, and marks another of the main obstacles, but beyond there the canal is clear for most of the final two miles to Bury, before the final lengths are infilled and largely obliterated, with the Bridge Trading Estate occupying the site of the town’s canal basins.

The Radcliffe to Bury length is the site for another development, this time by Manchester Ship Canal owners Peel. The site for what’s described as a ‘parkland community’, with 3000 homes plus schools and other facilities, includes Elton Reservoir, the canal’s water supply, as well as a length of the canal. It’s at a much earlier stage in the planning process, but looks likely to provide towpath improvements, canal dredging and channel restoration, plus new canal bridges with navigable headroom.

What it won’t do is remove any more of the blockages to navigation. But with developments happening on both sides of it, the likelihood of the key obstruction at Water Street Bridge in Radcliffe being dealt with is increasing. Not only are the Greater Manchester Combined Authority, Bury Council and the Canal Society in discussions on how to find the £4m cost, but the Society also points to the vital support from communities along the canal. Local schools, a litter pickers volunteer group, a running club and community body Growing Together Radcliffe are all supporters of the canal. Getting people like that on-side improves the chances of future planning decisions favouring the canal.

And then what?

If Water Lane Bridge can be dealt with, then together with repairs of the breach it will create a five-mile navigable length from Hall Lane to the edge of Bury. The next objective could be to restore the locks at Nob End, and reopen down to Ringley. And if the case can be made to include the canal in the next development scheme at Salford, that would leave a ‘missing link’ of around five miles to link it all up. It could happen…

To find out more or to get involved in the restoration, see the Manchester Bolton & Bury Canal Society’s website mbbcs.org.uk

As featured in the December 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the December 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here