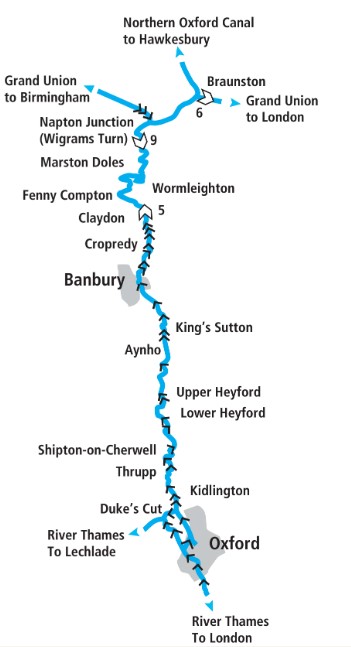

In the first part of our guide to the canal which formed the first connection from the Thames to the Midlands, we follow the southern length of the Oxford Canal from Oxford city to Napton

Historically the Oxford Canal began at its north end, where today it meets the Coventry Canal at Hawkesbury Junction. Construction work began near here in 1769, and it didn’t arrive at its southern terminus in Oxford until 1790. But we’re going to follow it in the opposite direction, beginning at the Thames and heading northwards.

The approach to the canal from the Thames in Oxford is via Isis Lock, spanned by a characteristic iron towpath bridge

Leaving the Thames

Actually, to stick with the history, as opened in 1790 it didn’t connect with the Thames at all, it ended at a dead-end basin and any cargoes would have to be transhipped to river boats. And that accounts for the slightly odd layout of the entry to the canal for boats arriving from the River Thames. A few hundred yards north of Osney Bridge on the river, a backwater called the Sheepwash Channel heads of eastwards under a towpath bridge. This leads (via an interesting old railway swingbridge – it hasn’t swung since the sidings which crossed it were closed in the 1980s, but it’s been kept as a historic feature) to a junction of backwaters.

Take care not to be pulled by the current towards the unnavigable channel that heads to your right, as you turn sharp left to enter Isis Lock (also known by the slightly less attractive name of Louse Lock). Its chamber is spanned by a distinctive Horseley Iron Works cast iron towpath bridge of a style more common on the northern section of the canal – and also familiar on the Black Country waterways. It’s a narrow-beam lock (this is a narrow canal, built for craft of 7ft wide) but it hasn’t always been so. When the connection from the Thames to the canal was first created soon after the canal was completed, it appears to have used some kind of removable weir – which meant that every time it was used, the canal’s southernmost length and terminal basins were emptied, and would have to be refilled. Soon sense prevailed and a lock was built, originally wide-beam so that river barges could use it, but rebuilt to the current CRUISE GUIDE dimensions once they’d stopped trading into the canal basins.

Anyway today’s lock is a typical southern Oxford lock with single gates at each end, and it leads immediately to another junction: bear left to continue along the canal, or sharp right for a short dead-end length used for moorings. This once continued to the original terminal basins, closed and filled in in the 1930s and used as the site for the new Nufeld College and a car park. Periodically in recent years there have been proposals to turn the car park back into a canal basin, but they’ve yet to come to anything.

Continuing northwards from the lock, the canal passes through Oxford city centre’s western fringe. You won’t see the historic college buildings of the university city (they’re mainly over to the east side, but they and the city’s other sights are within reasonable walking distance). However you will see a pleasant length of urban waterway. An assortment of new and old buildings accompany the canal as it passes what was once an industrial area on the left, with the impressive St Barnabas’ Church and a handy boatyard on the right hand side.

Cruising through the outskirts of Oxford

As the canal gradually leaves the city behind, you’ll be introduced to one of the southern section’s characteristic feature – liftbridges. Originally there were no fewer than 38 of these between Oxford and the summit. Many have since disappeared, and of those that remain, a fair number are generally left open, but you will need to operate some particularly near the south end of the canal. Operation of most of them is pretty basic: you just pull down on the chains attached to the balance beams to open the bridge. Leave them open or closed, as you found them.

A couple of locks begin the gentle climb northwards; just before the second one is a junction with Duke’s Cut branching of on the left. This forms a handy short-cut to the upper Thames for boaters not wanting to visit Oxford; it links to a weir stream that joins the main river navigation just above King’s Lock. Note the unusual lock at the start of the Cut: it was built with two full sets of gates, one facing each way, so that in the days when the Thames water levels were less reliably controlled it could cope with a change of level in either direction. These days it’s always uphill in the direction from the canal to the river, so the lock just has the standard gates, but you can still see the recesses where the other gates were.

Passing the junction with Duke’s Cut

Passing Wolvercote and Kidlington, the canal’s route begins to wind a little more as it reaches the canalside village of Thrupp. A couple of waterside pubs and a facilities block provide for boaters’ needs, then power-operated liftbridge followed by a sharp left turn and a broad river-like section marks where the canal used a length of the former course of the River Cherwell.

Passing the picturesque canalside village of Thrupp

Climbing the Cherwell Valley

We’re now entering one of the most attractive and secluded sections of the canal, with few roads passing nearby, and just the railway and the River Cherwell for company. Incidentally the railway bridge over the canal at Shipton-on-Cherwell was the scene of a terrible accident in 1874 when a train derailed, one carriage landed in the canal, and 34 people lost their lives.

A particularly quiet and secluded length in the Cherwell Valley near Tackley

At Shipton Weir Lock the canal joins the river: the lock is a shallow water-control lock with a rise of just a couple of feet, but its chamber is widened to about three times the normal width to ensure that enough water is passed through it to keep the deeper locks between there and Oxford supplied. River and canal combine their courses for a mile or so – watch out for a few tight bends – before separating again on the approach to Baker’s Lock.

Leaving Dashwood Lock, south of Heyford

There’s another pub at Enslow, but then there’s very little sign of habitation – and no road bridges at all – for the next five miles as the canal follows the quiet windings of the Cherwell Valley to Lower Heyford. Occasional locks keep up the navigation interest as the canal passes through wooded landscapes before reaching more open countryside.

Handy boatyard at Lower Heyford

Lower Heyford has a very convenient canalside railway station – and the line no longer carries the regular heavy coal trains all night which once kept me awake while moored there. Similarly Upper Heyford is also a more peaceful mooring since the departure of the fighter jets which operated from the former air base. Somerton Deep Lock at 12ft rise is the deepest on the canal.

Typical Oxford Canal liftbridge near Somerton

Three miles further on at Aynho, the canal once again crosses the River Cherwell on the level, with another diamond-shaped lock to increase the amount of water passed through (although it would need to be considerably larger to pass the same amount of water as Somerton Deep Lock). Aynho village itself is a mile to the east, with a separate small canalside settlement of Aynho Wharf featuring a boatyard and a pub.

Leaving the odd-shaped Aynho Weir Lock

What was once a peaceful stretch of canal continuing up the Cherwell Valley towards Banbury has been rather less quiet since the M40 opened some 30 years ago, crossing the canal three times altogether, but it’s still a pleasant length with numerous liftbridges. King’s Sutton is an attractive old village that’s physically close to the canal, but the lack of a bridge over the river means that it can only be reached by a walk of almost two miles either north from Nell Bridge or south from Twyford Bridge – I can’t help wondering if a footbridge and footpath might perhaps create an easier access?

Passing through Banbury

On the last couple of miles into Banbury the canal passes the sadly burnt-out remains of the lock cottage at Grant’s Lock before arriving in the town, the largest settlement on the canal between Oxford and Rugby and a useful stopping point for shops and pubs. Banbury’s canalside has seen changes over the years, not always happy ones, from the filling-in of the original basin to create a bus station in the 1960s to its more recent replacement with retail developments. But one important survival is Tooley’s Boatyard, with its historic drydock and its connections to waterways revival pioneer Tom Rolt, which now faces the town’s museum across the canal.

Passing Banbury town centre, with the historic Tooley’s Boatyard on the left

Leaving Banbury behind, the gentle climb which has seen us rise through 17 locks in 27 miles from Oxford begins to steepen just a little, with locks occurring more frequently as the canal climbs to Cropredy. There’s been a change to the locks, too: since Banbury the big single bottom gates have been replaced by the more usual arrangement of pairs of bottom gates. It’s been said that this represented a cost-cutting measure as the canal constructors headed southwards and funds ran short – but wouldn’t the reduction in carpentry work involved in a single gate be balanced out by the increased masonry involved in a slightly longer lock chamber to allow room for the bigger gate to swing open?

The climb to the summit level

Cropredy is a picturesque village with pubs, shop and church, which comes to life once a year for the annual Fairport Convention folk festival, a favourite with many boaters – and which was rather more rudely awoken in 1644 when the Royalists defeated the Parliamentarians in an early Civil War battle.

The canal climbs through Cropredy, pretty village and home to the annual Fairport Convention music festival

We’re now on the final stages of the climb, with three locks followed by the Claydon flight of five bringing us to the summit level, 384ft about sea level.

Arriving on the canal’s summit level at the top of Claydon Locks

But what’s notable about it isn’t its height (some 20 or so other canals climb higher than this); it’s the length of the summit (11 miles) when compared to the actual distance of just four miles as the crow flies from the top lock at Claydon to the start of the Napton flight. It’s been popular to blame early engineer James Brindley for the extraordinarily indirect route, twisting and turning and running around three sides of Wormleighton Hill as it clings to the contour, but it seems more likely that the final design was down to his pupil Samuel Simcock, who took over after Brindley died in 1772 during the early stages of construction. Some wag accused Simcock of wanting to write his initials across the county in water…

On the remote and winding summit level

But although it must have been frustrating for working boat crews with a destination to reach, for leisure boaters it’s a splendid length of upland rural canal, and there are several heritage features to look out for. There’s the former Fenny Compton Tunnel (see below), long since opened out into a long narrow cutting, and now notable as the only straight section anywhere on the summit. Just south of the ‘tunnel’ there’s the final liftbridge – it’s said that they were another economy measure, and that’s why they were only used towards the south end of the canal as the money ran short. A side bridge (complete with a bridge number) spans a feeder bringing water in from Boddington Reservoir. This has the historical curiosity of having been largely paid for by a different canal company, the Warwick & Napton (now part of the Grand Union) as it was built to supply their canal. The water would feed into the Warwick & Napton Canal via the Oxford Canal at Napton Junction (and on its way there the Oxford company would get ‘free’ use of the water at Napton Locks). Finally, look out for a sign (sometimes half hidden in the undergrowth) marking where the former Stratford-upon-Avon & Midland Junction Railway once crossed the canal on its meandering route across the south Midlands.

And speaking of railways… If the M40 has had its impact on the canal around Banbury, it’s HS2 that’s going to make itself felt on the summit section. Work is under way on this length of the new high speed line, which will cross the canal towards the north of its summit level, between Wormleighton and Priors Hardwick. Oh and one final feature of the summit: a welcome canalside pub and nearby boatyard at Fenny Compton.

A pair of locks at Marston Doles mark the beginning of the descent, followed not long after by the main Napton flight. The locks descend northwards in an attractive setting with a view of Napton’s hill-top windmill ahead – and rather unexpectedly a field of water buffaloes on the right. Below the bottom lock stands another canalside pub, with Napton-on-the-Hill village a short walk up the lane. The canal then takes a circuitous route around the bottom of the hill, arriving at Napton Junction.

Descending Napton Locks

Here, what was originally the Warwick & Napton Canal comes in from the left, forming part of today’s Grand Union Canal Main Line from London to Birmingham. Turn left here for Birmingham – it’s covered by our cruise guide to the northern part of the Grand Union. Rather curiously, for the next five miles to Braunston Turn, what we’ll be travelling on is still the northbound Oxford Canal, but also forms part of the southbound Grand Union route. And we’ll cover it, as well as the remainder of the Oxford Canal’s route north to its terminus at Hawkesbury Junction, in the second part of our Oxford Canal cruise guide.

HISTORY: The Tunnel that isn’t…

Just south of Fenny Compton Wharf, the Oxford Canal’s summit level enters a long straight cutting. That it’s the only cutting and the only straight section on the summit, which for its other 10 miles winds this way and that as it follows the contours to avoid earthworks, gives a hint of its origin: this was once Fenny Compton Tunnel. Brick-lined like most canal tunnels, it was 1138 yards long, and as was the norm for long tunnels of the time, it wasn’t equipped with a towpath. But rather than relying on the usual method of propulsion in these cases – the boat crews lying on their backs and ‘legging’ the boat through using their feet against the tunnel walls – there were wooden blocks with iron rings set in the tunnel walls every few yards, which the boatmen would use to pull themselves along.

The ‘straight mile’ – a cutting which was once a tunnel

The tunnel was only wide enough for a single boat to pass, but unusually it is reported that it was equipped with passing places 16ft wide. Even so, the tunnel appears to have been a bottleneck and source of delays. In 1838 the canal company took the opportunity to buy some of the land above the tunnel and opened-out a 350-yard section near the middle of the tunnel into a cutting, leaving two shorter tunnels 336 yards and 452 yards long. But it was still an inconvenience, so in 1868 the southern of these two was also opened out, followed two years later by the northern one. A towpath was created alongside the resulting long straight cutting, and as the original ‘horse path’ over the tunnel top had crossed from one side of the canal to the other, a Horseley Iron Works cast-iron bridge was erected to carry the towpath across the cutting.

Along with the towpath bridge, there are still clues to its history in the form of traces of the original tunnel masonry at water level, and the name – working boat people still referred to it as ‘The Tunnel’, as do today’s boaters, even though it hasn’t been a tunnel for over a century and a half. Fenny Compton isn’t the only ‘lost’ tunnel on the Oxford Canal: there were two more on the northern part of the canal.