In the second part of our guide to the link from Oxford to the Midlands, we follow the northern length from Napton to Hawkesbury

Leaving the South Oxford ‘by-way’

“It was obvious that we had emerged from a by-way onto a main road”. That’s a description of reaching Napton Junction and leaving the southern section of the Oxford Canal to join the length of canal shared between the northern Oxford and the Grand Union route from London to Birmingham. It comes from Narrow Boat, the book by LTC (Tom) Rolt whose 1944 is credited with providing the spark that began the modern revival of the inland waterways for leisure, following the decline of freight traffic.

It might not seem quite such an appropriate comparison today. Rolt had passed just one boat (a horse-drawn working boat taking coal to Banbury) in a whole July day’s boating prior to arriving at Napton. Today it would be unusual not to see a few dozen craft at that time of year on this popular cruising route. But there’s still something of the same feeling of change as you pass Napton Junction, where the northern Grand Union enters under a concrete towpath bridge on your left.

For starters, while the southern Oxford was built for narrowboats 7ft wide, from Napton onwards we’re now on a wide-beam waterway. As already mentioned, this section of canal, although it was built as (and remained) part of the Oxford Canal, also forms part of the Grand Union’s route. And in the 1930s, the series of mergers which created the Grand Union from a series of earlier canal companies was followed by a major improvement programme to complete a wide-beam route from London to Birmingham. Narrow locks from Napton to Birmingham were replaced with wide ones, narrow bridges were widened (hence the concrete span at the junction), and channels were enlarged with the banks rebuilt in concrete piling.

One of several bridges on blind bends on the ‘shared’ section from Napton to Braunston

So as part of this work, the ‘shared’ length of the Oxford Canal from Napton to Braunston also had to be widened. There aren’t any locks on this length, but 1930s concrete bridges, piled banks and a wider channel give it a different feel. However for the first few miles it still follows the rather meandering route of the original Oxford Canal, built (as were many early canals) to follow the contours of the land. This means that a couple of main road bridges are approached by a blind bend on either side – note the various dents in the concrete banks where boaters have unexpectedly met somebody here, and remember to hoot your horn!

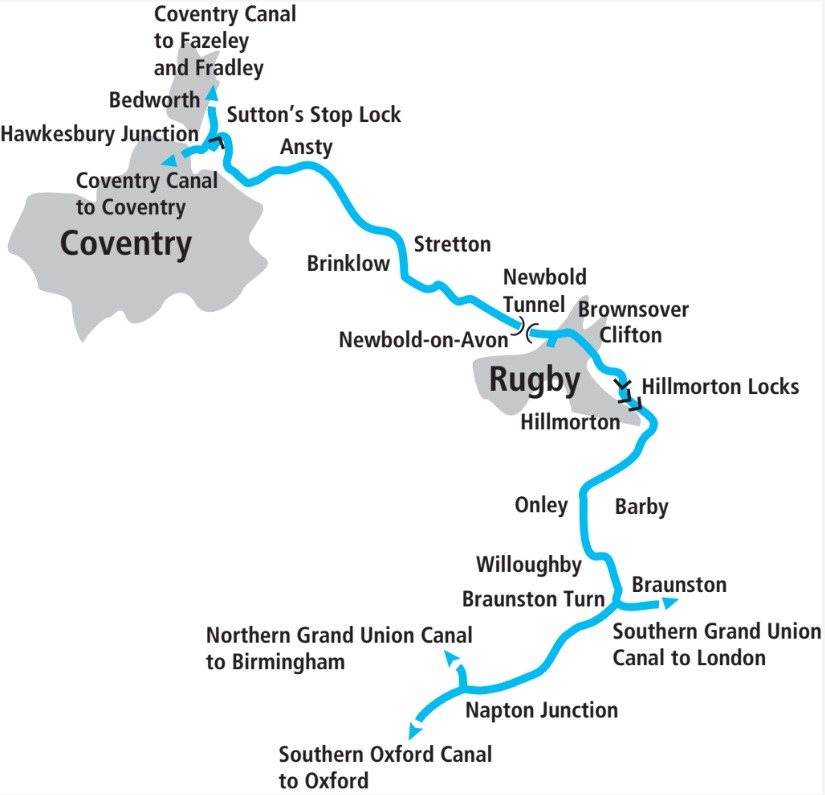

Incidentally it’s one of the oddities of the canal system that – as you’ll see from the map – while we’re travelling northbound on the Oxford, boats travelling northbound on the Grand Union will be passing us in the opposite direction! And another quirk of history is that because the Oxford Canal Company had opened their route some decades before the predecessors of the Grand Union had built theirs, it gave the Oxford the right to charge heavy tolls on through traffic using those five miles, helping to keep the Oxford in profit right up to the end of its independent existence. But I digress…

Near Wolfhampcote on the shared Oxford / Grand Union length

Approaching Braunston, you’ll become aware of another change to the character of the northern part of the Oxford Canal since it was built. Approaching Wolfhampcote the canal abandons its winding contour-hugging course and enters a long, gently curving cutting, beyond which a long straight embankment leads to the next junction at Braunston. The reason for this change of style (there have been few cuttings or embankments since Oxford) is that this is the first of many sections on the northern Oxford Canal which were straightened in the 1830s in an attempt to stave-off competition from other canals (either already built or planned) by shortening the canal’s route by some 13 miles altogether.

This first big meander cut off by the improvement scheme shortened the length by almost three miles, bypassed a tunnel, and led to today’s layout of Braunston Turn, where the Grand Union and Oxford canals part company.

The distinctive Braunston Turn, with its twin Hawkesbury Ironworks towpath bridges

Left at Braunston Turn

Braunston Turn takes the form of a T-junction with a triangular island, crossed by a set of two cast iron towpath bridges: to head south down the Grand Union you bear right of the island to pass under the right-hand bridge; we’ll bear left under the left-hand bridge to continue north on the Oxford Canal. But do consider pausing in Braunston first (you can get closer to the village by taking the right turn, and then turning around at the marina entrance to get back) as this small Northamptonshire village, not widely known other than to waterways folk, is a special place on the waterways system. As a meeting point of waterways, it was a focus for working boat life, with many from the boating families married and buried at the church in the village. It was also a centre for boatbuilding; today still it’s a busy boating centre with marina, boatyards and other businesses. And every June it hosts the with its colourful (and sometimes chaotic) daily parades of heritage boats.

But back to Braunston Turn, and speaking of the cast iron bridges at the junction, from here onwards you’ll see a number of these, made at Horseley Iron Works near Wolverhampton, which were used to carry the towpath over the entrances to various arms remaining from the original route of the canal before it was shortened.

The canal is now not only leaving Braunston behind (look over your right shoulder for some fine views of Braunston Church on its prominent hill-top site), but it’s also leaving the high ground behind for gentler rolling Midland countryside. That didn’t stop the original builders from putting plenty of bends into its route, many of which were straightened out in the 1830s improvement scheme. You can often spot the difference between the winding surviving sections of the original route, and the straight cuttings and embankments dating from the later improvements.

A glimpse astern of Braunston Church spire as the canal heads for Hillmorton

Although the canal continues with its broader channel and less ‘by-way’ like appearance (to us Tom Rolt’s expression), it is officially back to being a narrow canal since Braunston. I say ‘officially’ because since the 1930s there’s been nothing to physically prevent those in wider craft from cruising this section of it. Few would have wanted to (any that ventured this way wouldn’t have been able to get any further than Hillmorton Locks anyway), but in recent years as the numbers of widebeams have increased, there have been issues with them passing other craft while using this length to get to and from moorings. The Canal & River Trust’s view is that this is a narrow canal, and any such movements should be booked.

Cruising northwards near Onley

Busiest locks on the canal system

Passing Willoughby and Barby and a rare canalside pub at Hillmorton, the canal takes a left turn and reaches Hillmorton Locks. In another contrast with the southern lengths of the canal which average out at not far short of a lock every mile, these are the only three on the entire northern section. In another sign that it’s less of a by-way, they were duplicated side by side to cope with heavy traffic – and unlike many such locks, both chambers remain in use today. That’s just as well, as when both locks of each pair are totalled they’ve come out as the busiest locks on the network in the annual lockage report for several years running.

Busy scene at Hillmorton, busiest locks on the canal network

Those with an eye for waterways heritage may spot a couple of interesting features. Firstly a pair of old 19th century iron lock gates (the Oxford was an early user of iron and there are one or two sets still in use on the canal) were laid out on the canal bank below the locks a few years ago when they were no longer repairable. And secondly you can still see the (out of use) interconnecting paddles between the parallel locks, which enabled each lock to be used as a water-saving ‘side pond’ for its partner.

The canal is now passing the outskirts of Rugby, but for much of the way it keeps its rural appearance thanks to a railway embankment separating canal from town. A couple of aqueducts mark another stretch of canal dating from the 1830s as the canal passes through the residential areas to the north of the town (bridge 59 is the closest for walking into Rugby for its shops and attractions), and an old arm (a remnant of the canal’s original line, entered under a cast iron bridge) leads to the town wharf and boatyard.

Newbold Tunnel, now the only one on the Oxford Canal

The only tunnel on the canal

Gradually returning to the countryside, the canal reaches Newbold with its canalside pub and Newbold Tunnel. This is the only tunnel on the canal (or at least it has been since the 19th Century, when Fenny Compton Tunnel on the southern length was rebuilt as a cutting), and from its twin towpaths and generous dimensions it clearly dates from the 1830s rebuilding (when it replaced an older, narrower tunnel on a slightly different route). It’s wide enough to pass in, but given that it’s only 250 yards long you may prefer to wait if anything’s coming. Incidentally you can still find the bricked-up entrance of the original tunnel some distance away near the parish church’s churchyard.

A winding length near Hungerfield dating from the original construction of the canal in the 1770s…

…and a straight, wide section with deep cutting and high bridges dating from the 1830s straightenings

By the far end of the tunnel the surroundings are completely rural again, and remain so for the remainder of the route. There are few villages close to the line (Brinklow is a 15-minute walk away), and it would be a quiet length were it not for the West Coast Main Line railway keeping the canal company for two or three miles. Look out for Brinklow Arches: a rare example of a significant aqueduct on the original canal, most of the arches have since been filled in. You’ll also pass Stretton Stop, a narrowing of the canal where tolls were once charged (and now home to a boatyard).

Heading for Hawkesbury

Ansty is a canalside village complete with pub, and leads to the final winding lengths (disturbed by the nearby M6 for a little of the way) leading towards the end of the canal at Hawkesbury. Here, on the outskirts of Coventry, it meets the Coventry Canal. A long left-hand bend, skirting the site of the former power station (its supplies of coal were a regular canal traffic), approaches what’s officially known as Hawkesbury Junction. However it was known to generations of boat families (who often tied up here waiting for orders for cargoes of coal to carry south) as Sutton’s Stop. This was from the name of an early lock-keeper at the stop-lock, built to separate the waters of the two canal companies.

Tight turn from the Oxford to the Coventry Canal at Hawkesbury Junction

One of the few stop-locks still in use today, it lowers boats just a few inches to the level of the Coventry Canal – and on leaving the lock, there’s an ‘interesting’ turn to make, under yet another Horseley Iron Works towpath bridge. For boats heading for the dead-end length of the Coventry Canal leading into the city centre, it’s easy enough – just a right and a left. But for the majority who are heading north it’s a 180-degree U-turn to the right (and a tight one for those in full-length boats) leading straight into another narrowing where tolls were once charged for the Coventry Canal. Take it carefully!