This Cheshire river has seen a lot of changes in its 300 years as a navigation – but it retains its attractiveness as a quiet cruising route, and there are many signs of its long history still to be seen

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

The River Weaver is different. How? Well, by way of explanation… regular readers will know that we often start these cruise guide articles with something along the lines of “The XYZ Canal was designed by engineer James Kingdom Telford and opened in 1823, running for 30 miles via 17 locks built to take boats 72ft long by 7ft wide from A to B, and was busy with coal boats until the arrival of the railway…” And more often than not, you’ll find that it still runs from A to B, it’s still 30 miles long, and it still has 17 locks, and woe betide anyone who tries to cruise it in anything much bigger than 72 feet by 7! But as I said, the Weaver isn’t like that. As we’ll see, it’s seen many changes in its 250-year life as a navigation; in many ways it’s a completely different waterway – and as you cruise along this attractive but underused Cheshire river, there’s evidence of the changes that have been made over the centuries.

Still, let’s start the potted history with the usual information. The driving force behind the Weaver Navigation was the Cheshire salt-mining trade – it needed transport to bring in coal to heat the salt-pans to refine the salt, and to take the finished product away to market. After a few false starts when opposition from land carriers and others led to its Bill being defeated in parliament, the River Weaver Navigation got its Act of Parliament in 1721, in the early days of the industrial revolution and before the main canal-building era. The river was made navigable by erecting eleven weirs to maintain the water level, each one accompanied by a lock. It opened in 1732, running from Winsford via Northwich to where the river became tidal and met the Mersey estuary below Frodsham. It was a little over 18 miles long, and the locks were constructed to take ‘flats’ (the local sailing barges of the Mersey and surrounding waters) carrying around 40 tons. I can find no record of the locks’ dimensions, other than that they were mainly timber-built and “small”. But no matter, because unlike most canals and many rivers which (as I mentioned above) have kept their original dimensions to this day, the Weaver locks were already being rebuilt in the 1760s (still very early in the canal age) to larger dimensions to take bigger sailing flats measuring around 68ft by 17ft.

But that was just the start of things. By the 1830s, the locks were being enlarged again, to 88ft by 18ft; only a few years later new locks 100ft by 22ft were being built alongside the existing ones. Twenty years later, as many other waterways were suffering from the impact of competition from railways, the Weaver Navigation was enlarging is locks yet again, up to 200ft by 40ft to take a seagoing vessel or a steam barge accompanied by three unpowered lighters. And at the same time the river was being straightened and the number of locks reduced by replacing two or more locks and weirs with one deeper one. Today, eleven original locks have been replaced by just four. But don’t be put off by thoughts of cruising on an aquatic motorway shared with giant freight barges that’s out of all character with our cruising waterways. It’s not like that at all, it’s still a lovely river, but it’s one that’s seen a few changes, and you can appreciate them as you cruise…

How most boaters arrive on the River Weaaver: approaching the Anderton Lift from the Trent & Mersey Canal

And the most spectacular of the changes to the river over the years is how you get to it from the rest of the waterways network. As originally opened, the Weaver Navigation was only accessible by water from the Mersey estuary; however, at Anderton just north of Northwich it passed within a few yards of the Trent & Mersey Canal – but with the canal 50ft higher up the valley side. So today almost all visiting boats arrive from the Trent & Mersey Canal via the Anderton Boat Lift, opened in 1875 to connect the waterways together. It’s now the waterways network’s only operational vertical boat lift and one of only two working boat lifts of any kind in Britain. And it really is a unique experience for boaters, to cruise into one of its metal ‘caissons’ (tanks) and be lowered by 50ft from canal to river inside its giant iron framework. On the practicalities of using it: you do need to book your passage these days via the Canal & River Trust website, but there’s no charge. And while you’re there, take a look at the lift exhibition.

Anderton Lift Visitor Centre

Anderton Lift Visitor Centre

See models and interactive displays about the famous boat lift in this exhibition attached to its operations centre. You can book ‘behind the scenes’ tours of the lift, and a children’s play area including a maze made from the redundant counterbalance weights dating from before its restoration

Having arrived at somewhere not far from the mid-point of the navigation, you have a choice. Left for Northwich and Winsford; right for a long rural stretch leading eventually to Runcorn. We’ll take the left turn first, and it’s quite a sharp left turn from the lift’s exit basin into the Weaver – but it’s a wide river, so you should have no problems. Be aware, as ever on rivers, that there’s a current to allow for.

We’ve arrived on the river in what was until not that long ago a heavily industrial area, with a giant chemical works (the Cheshire chemical industry is still important) on the north west bank, but in recent years it’s seen a great deal of reclamation work, and the river now passes between nature parks, green spaces and areas of woodland criss-crossed by paths for most of the way to Northwich. Look out for the River Dane joining on the left: nothing came of plans to make it navigable, but it impinges on the canal system a couple of times where it’s crossed by a couple of significant aqueducts carrying the Trent & Mersey Canal at Croxton and the Macclesfield Canal just below Bosley Locks.

Northwich town is a useful stopping point which came in for some criticism from some quarters a few years ago for neglecting its riverside, but has made an effort in recent years to improve matters with the Baron’s Quay waterside development including restaurants, bars and leisure attractions, and hosts an annual river festival. A more traditional attraction for boaters is the two large power-operated swing bridges which carry main roads across the river in the town. They’re actually the first bridges since we joined the river (crossings are fairly infrequent on the Weaver) and are built around 120 years ago to what was at the time a state-of-the-art design, possibly the country’s oldest electrically powered bridges, and with much of the weight supported by a large hollow metal pontoon floating in a water-filled chamber. You’re unlikely to need any of the bridges on the river to be swung, as most inland craft will easily fit underneath them all, but they do still need to open for the occasional masted vessel, or the regular public trips on the lower part of the river by restored historic Manchester Ship Canal tug-tender the Daniel Adamson.

Dock Road Edwardian Pumping Station

Dock Road Edwardian Pumping Station

On the east bank of the river just upstream of Northwich town centre is a small circular castellated building. This listed structure contains two unusual surviving early 20th century gas engines formerly used for pumping sewage, and is sometimes open to the public.

Leaving the town and passing under a high railway viaduct (they’re rather a feature of the Weaver; this one carries the Chester to Manchester line), we reach our first lock. Or perhaps I should say ‘Locks’ – because, like all the remaining four locks on the river, Hunt’s Locks are duplicated, side by side. Or perhaps I shouldn’t, as like all of them, only one chamber is in use. In this case it’s the smaller chamber, which looks to date from the enlargement to 88ft by 18ft. There’s no commercial freight on the river these days (and hasn’t been any regularly since around the 1990s), but if it were ever to re-start, the large locks would need putting back into use. The locks are still keeper-operated, so familiarise yourself with the opening hours (see boaters’ notes) and be aware that in my experience they tend to close promptly. One interesting historic feature which survives (sadly no longer in use) is that at each end of each pair of locks, there are a pair of railway-style semaphore signals which indicated to boats whether the lock was ready for them.

Leaving Hunt’s Locks; in the background is one of several impressive railway viaducts that cross the Weaver valley

A long straight cutting (you can see where old loops of the river were cut off by the straightening; they are home to an interesting selection of craft) leads to a rare fixed road bridge (limiting headroom on the river to 30ft), an impressive 1930s steel girder bridge carrying the 1930s Northwich bypass and known locally (for reasons which will be obvious) as the Blue Bridge. By now the river is flowing through an impressively straight, deep, steep-sided valley which is spanned by another tall rail viaduct (this time carrying the West Coast Main Line) as it approaches Vale Royal Locks. Once again it’s the smaller chamber that’s in normal use. This is a shame because it means there is no longer the opportunity to see an unusual system of power operation that was fitted to the larger locks: water turbines harnessed the power of the head of water between the levels above and below the locks, and used it to open and close the lock gates.

The steep-sided and wooded valley continues as the navigation follows the Vale Royal Cut to Newbridge swing bridge, the lowest on the river but still high enough not to need swinging for most inland craft. The exact height limit varies with the level of water in the river, but a gauge mounted on the vertical stone river bank indicates what headroom is available. This was the site of one of the locks that disappeared during the reduction from the original eleven locks to five: you can still see a lock gate recess in one of the channel walls by the bridge. At Newbridge, the long straight section leads to a more winding length, and the first signs of industry since we left Anderton in the form of a large rock salt mine on the west bank which produces much of the supply for gritting roads in winter – as evidenced by the large heaps of it all around. A final length of reclaimed land on the east bank, once covered with salt workings and their associated railway sidings, leads to Winsford, the head of navigation. The official limit of CRT jurisdiction is marked by visitor moorings and two non-opening bridges with around 10ft headroom, but boaters may be tempted to continue to reach a remarkable feature of the river.

Unexpectedly, just around a bend it suddenly widens into a large expanse of water, Winsford Bottom Flash, formed from salt mining subsidence and subsequent flooding of the land. But be wary of exploring it by boat – although it’s popular with small unpowered craft it’s very shallow, the deepest water isn’t in the middle, the bottom is soft mud, and if you do go badly aground it isn’t CRT’s responsibility (or anyone else’s) to rescue you. So if you do venture into the Flash, take it very gently and be prepared to back out at the first sign of grounding – and don’t blame us!

The Weaver was made navigable to serve the salt-mining industry, and this mine just north of Winsford is still in operation

As you might have guessed from the name, it’s followed (at least for those in small craft) by Winsford Top Flash. And that in turn is followed by an embankment crossing the river valley which carries the Middlewich Branch of the Shropshire Union Canal. Back in the optimistic days when canal supporters were proposing new waterways rather than fighting to keep the ones we’ve got, there was a suggestion of a link via a new boat lift – as if one boat lift on the Weaver wasn’t enough!

Anderton Nature Park

Anderton Nature Park

This is an area of the Northwich Woodlands reclaimed from many years of industrial use. It is now criss-crossed by paths and a haven for wildlife, especially wildflowers which can be discovered by following the Wildflower Trail (leaflets available, in season, from the Rangers’ Office and the Anderton Lift Visitor Centre).

Returning to Anderton, we’ll now follow the Weaver downstream, past a short industrial length and another road swing bridge (something of an issue locally at the moment), as it’s only wide enough for one-way road traffic and new residential developments look likely to increase traffic. Housing and industry are soon left behind as the river enters its almost entirely rural lower middle reaches. Barnton Cut, one of the longer lengths of artificial channel on the river at almost two miles, leads to Saltersford Locks. In this case it’s the large lock that’s still in use, and a single narrowboat is rather dwarfed by the huge chamber. These lower reaches of the river downstream of Anderton continued to carry freight for longer than the upper sections, and are still maintained to larger navigable dimensions – and the interesting turbine-driven gate mechanisms at both this lock and Dutton Lock were replaced by more modern electric gear.

Saltersford Locks: the lock in use is the larger one on the right, built to take vessels up to 200ft by 40ft

Below Saltersford the navigation rejoins the natural river for an attractive rural length, briefly interrupted by the huge Acton Swing Bridge, before we reach the last of the remaining four locks on the river at Dutton. Yet another railway viaduct (the West Coast Main Line again) leads into the quietest and most remote length of the river – remarkably for a relatively populous area of the country there are four miles with no bridges, no roads running nearby, and little sign of habitation for much of the way. Look out for more traces of the river’s history in the form of the abutments of a long-gone bridge, the remains of another lost lock (visible from the path on the east bank), and the Frodsham Cut heading off to the left. This used to lead via Frodsham Lock to the river’s tidal reaches (now only semi-tidal since the building of the Manchester Ship Canal); its restoration was proposed some years ago to provide easy access to Frodsham without having to use the Ship Canal, but the scheme didn’t get as far as practical work beginning.

Since the old cut and lock were abandoned, the navigation has continued via the four-mile Weston Canal, an artificial waterway running to the east of the river. It’s crossed by the last of the big road swing bridges, another electric-powered one built to the float-assisted design and carrying a major road (and restored in recent years) at Sutton, followed by the final high-level railway viaduct carrying the Runcorn to Chester line.

Another impressive railway viaduct spans the river near Dutton

For the last two miles of the Weston Canal, industry returns in the form of a chemical works stretching along the east bank. It’s not the most scenic of waterways but it forms a useful link for adventurous boaters heading via the Manchester Ship Canal to Ellesmere Port, Manchester or the Mersey Estuary crossing and Liverpool. The link is via the connecting Weston Marsh Lock, for which passages need to be booked with CRT. Few boats venture beyond there, a second route to the Ship Canal via Weston Point Docks having fallen out of use in recent decades with changes to the use of the docks, making this a dead-end with no public mooring at the terminus. However, boaters may wish to navigate it as an out-and-back trip (there’s plenty of room to turn at the end), firstly simply for completeness and secondly to look out on the right for the derelict entrance lock to the former Runcorn and Weston Canal. Until as late as the 1960s, this potentially very useful link provided a route via a flight of locks to the Bridgewater Canal at what is now the terminus of that canal’s Runcorn line, and if restored would make a second route onto the Weaver without the bureaucracy associated with a passage on the Ship Canal.

Sadly, it’s not an easy restoration for various reasons, but there’s a plan to reinstate the link which involves not one but two new boat lifts of different types! Could the Weaver become the waterway with the world’s biggest concentration of working boat lifts?

Boaters’ Notes

Remember the Weaver is a river navigation, and therefore high river levels and strong currents can be experienced following heavy rain. If in doubt, find somewhere safe to moor until water levels have reduced.

Locks are keeper operated: the hours are currently 8.30am to 5pm with last entry to each lock at 4.30pm, but do check the latest times on the CRT website.

Marsh Lock is used to access the Manchester Ship Canal. Passages need to be booked via the CRT website. Do note that there are strict conditions for taking inland craft on the Ship Canal including insurance and equipment requirements, plus a need for the correct charts and a certificate of seaworthiness (available from some local boatyards) as well as advance booking including a considerable fee.

Winsford Bottom Flash is very shallow (and the deepest water isn’t necessarily in the centre). If you do venture into it, take care and be aware that you are doing so at your own risk with no obligation for any navigation authority to rescue you.

Passages through the Anderton Lift need to be booked via the CRT website. There is no fee.

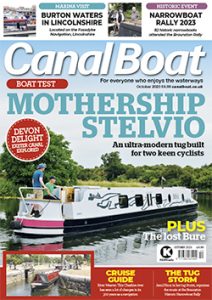

As featured in the October 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the October 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here