Three centuries of development have left us with a waterway on a larger scale than most of our network, with occasional large freight barges still at work and hope of a revival, but elsewhere signs of regeneration and reclamation following the demise of the coal mining that was its lifeblood.

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

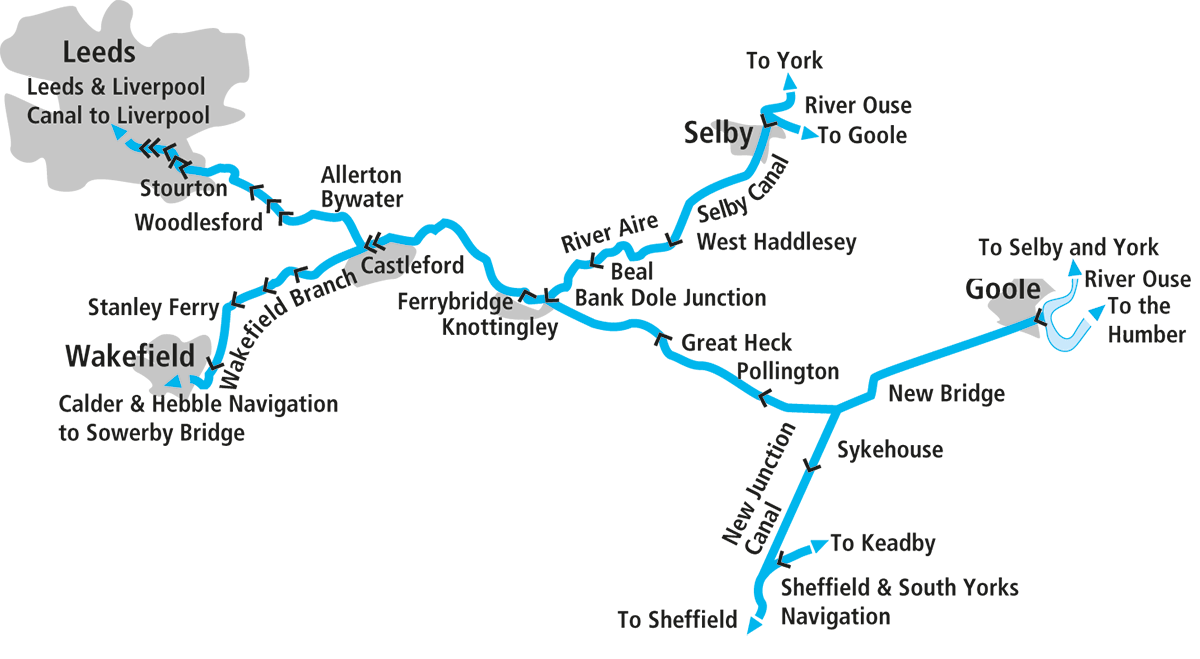

Usually with these cruise guides, it’s not difficult to decide where to start our journey along the waterway that’s the subject of the article. At most it’s a choice of two ends; with a dead-end waterway it’s even easier. But thanks to its complex history, there are four ways that boats might arrive on Yorkshire’s Aire & Calder Navigation – and which one boaters use, might depend not just on where they’re coming from, but also on their feelings about tidal waters, and the dimensions of their boat.

Usually with these cruise guides, it’s not difficult to decide where to start our journey along the waterway that’s the subject of the article. At most it’s a choice of two ends; with a dead-end waterway it’s even easier. But thanks to its complex history, there are four ways that boats might arrive on Yorkshire’s Aire & Calder Navigation – and which one boaters use, might depend not just on where they’re coming from, but also on their feelings about tidal waters, and the dimensions of their boat.

Yes, the Aire & Calder itself is a large commercial waterway (albeit ‘commercial’ almost only in name, given the current lull in freight traffic) which will take freight barges way above the sort of size that will fit on most of our inland waterways, but some of its connections are much more restricted.

Entering Knostrop Fall Lock, in the industrial outskirts of Leeds

For full-length narrowboats arriving from the main canal system (and similar length widebeams based on the Trent and connected broad waterways), the only way to get to the Aire & Calder involves a passage northwards from the Midlands down the entire length of the tidal Trent, all the way to Trent Falls, where it meets the Yorkshire Ouse (and not a trip to be undertaken lightly – it needs an adequately powerful, suitably equipped and reliable craft with experienced crew and knowledge of the river). Turning westward into the Ouse, they then have the choice of either entering the Aire & Calder at Goole Docks, or continuing up the Ouse to Selby and entering the Selby Canal branch of the Aire & Calder.

Passing moored freight barges at the approach to Goole Docks

For boats up to a little over 62ft long (the exact length depends on their width and hull shape), there’s an alternative route from the Trent which avoids the more adventurous lower reaches. Boats can leave the tideway at Keadby, then take the Stainforth & Keadby Canal to Bramwith, where they head north along the New Junction Canal to meet the Aire & Calder at Southfield Junction.

Another route is restricted to craft of 57ft by 14ft (a little longer if narrow beam): crossing the Pennines from the Manchester area via either the Rochdale or Huddersfield Canal, then taking the Calder & Hebble Navigation to join the Wakefield Branch of the Aire & Calder.

Finally, boats up to around 62ft by 14ft (and again, slightly longer if narrow beam) can arrive from the northwest via the Leeds & Liverpool Canal, joining the Aire & Calder main line at its western terminus in Leeds. And as it’s probably the most popular way to reach the A&C, that’s where we’re going to begin our journey.

We begin right in the heart of the city, where the Leeds & Liverpool Canal descends through its final 62ft by 14ft lock to enter the Aire & Calder, surrounded by new city centre developments, old warehouses that have found new uses, and the Leeds City railway station. It’s immediately apparent that we’ve joined a very different waterway – for starters we’ve left the canal behind and we’re joining a length of the River Aire. This river formed the basis of the main line of the Aire & Calder Navigation when it first opened to boats as long ago as 1704. We’re also on a much larger waterway, capable of taking sizeable freight barges carrying hundreds of tons – although that hasn’t always been the case, as you’ll see when you reach Leeds Lock after about half a mile.

Leeds Lock, situataed right in the city centre

The lock chamber that boats normally use isn’t much longer than those that you’ve been used to on the Leeds & Liverpool – but there is a third set of gates (at a slightly awkward angle) which were added later, lengthening it to around 140ft. This was done as part of a process of development that saw the Aire & Calder locks repeatedly enlarged from their original small size for bigger barges (and tugs pulling or pushing long trains of small rectangular unpowered boats known as ‘Tom Puddings’) to today’s dimensions where almost all will take at least a 210ft by 20ft vessel.

Like all the locks on the main line, Leeds Lock is mechanised and operated by boaters using a Canal & River Trust ‘Watermate’ (sanitary station) key.

Royal Armouries Museum

Royal Armouries Museum

Situated by the river in central Leeds, this is the national museum of arms and armour from ancient times to the present day – including everything from King Henry VIII’s armour to an Indian war elephant. There are daily live shows and combat demonstrations.

Today you won’t see any freight on this part of the river; the former Clarence Dock is now a marina, and the many industrial premises which once used the waterway have now been converted to new uses or been demolished. New buildings that replaced them include the Armouries Museum, right by the lock (and advertised by a cannon barrel mounted near the lockside – not something you see every day!) Leaving the city centre behind, the River Aire enters a more industrial area, and from here onwards you might even see the odd working barge. From still being quite busy until the 1990s, traffic had declined with the ending of coal mining and the reorganisation of the aggregates industry, to the point where commercial freight had completely died out on almost the entire length of the Aire & Calder; however, in recent years there have been signs of a revival with the start of regular sand traffic, loaded at Goole and unloaded in this area of Leeds, although hopes of setting up a major new freight terminal in Leeds have struggled to secure the necessary funding. If you do happen to meet a working barge, give them plenty of room, and bear in mind that they will be much less manoeuvrable than you, and that they will need deep water.

Thwaite Watermill

Thwaite Watermill

Variously used in the past to mill flint, oil seed, chalk and latterly to make putty, this mill just east of Leeds has been fully restored with working waterwheels, a collection of historical machinery, and the manager’s house restored to its 1940s appearance. It’s open weekends and school holidays

Look out for Thwaite Mills on your left, as the waterway leaves the built-up area before passing Woodlesford village. Soon you’re cruising through what now seems like a rural area with wooded banks, but was once heavily industrial with coal mines and opencast workings all around. One of these was the site of a breach in 1988 when the river burst through into a huge opencast mine: it is said that it took so much water to fill it up that the Aire flowed backwards for a couple of days. It was eventually pumped out and the bank reinstated so that the mining could be completed, but the scouring effect of the breach had damaged the navigation (even though it followed a separate channel from the river at this point) to the extent that a decision was made to divert it, and to replace two old locks with one new one at Lemonroyd – you’ll notice that it’s much deeper than the others on the waterway.

Leaving Lemonroyd, the navigation rejoins the river Aire for the first time since the outskirts of Leeds; another change that’s happened over the three centuries since it opened is that the waterway makes a great deal more use of artificial cuts and much less use of the river than it originally did. And that’s something we’ll see a lot more of further east… Three miles of river lead past Mickletown and Allerton Bywater to Castleford, where the Wakefield Branch (the ‘Calder’ bit of the navigation’s name) turns off. It’s a slightly unusual junction layout: to carry on down the Aire & Calder Main Line you’ll need to turn left into a flood lock (another odd-shaped extended chamber); for Wakefield, turn sharp right into the Calder. Don’t, whatever you do, go straight on – it leads to Castleford weir. If you moor up and walk past the weir on the rather striking modern footbridge leading to the town (a useful place for shops and pubs), you can still see the remains of an unfortunate barge which went the wrong way many years ago!

A deep wooded cutting in a former coal mining landscape near Mickletown

We’ll first follow the Wakefield Branch. Like the Leeds line it’s seen many changes: three miles of winding River Calder are followed by a long canal section dating from the 19th Century, which crosses the river via the unusual Stanley Ferry Aqueduct. There are actually two aqueducts: the original iron one was showing signs of distortion as a result of subsidence and there were fears for the consequences if a freight barge were to hit it, so a second parallel concrete one was added around 1980 – but both remain open for leisure craft. Not that there are any freight barges on the Wakefield line now, although there’s a plan for them to carry the output from a proposed quarry at Stanley Ferry.

Broadreach Flood Lock: A third set of gates (just behind the camera) allowed tugs and their trains of barges to pass through in one locking

Stanley Ferry is also the location of one of CRT’s two lock gate workshops – you may see completed gates stacked outside it awaiting delivery. Broad Reach Flood Lock is normally open at both ends, and leads back out onto the Calder for the final mile into Wakefield. Pass through the curiously named Fall Ing Lock, the first lock of the Calder & Hebble Navigation (unlike locks further up the C&H, it does take 70ft-plus boats) for visitor moorings to see the city, with its cathedral, Hepworth Gallery and rare bridge chapel (one of only three in the country), or to continue towards the Rochdale and Huddersfield canals.

Passing through the oddly-shaped Castleford Flood Lock

Back to Castleford, and the main line heads east, rejoining the river for a winding stretch past what is now Fairburn Ings Nature Reserve and a series of lakes, but was once another series of coal mines. At Ferrybridge the old Great North Road bridge crosses amid what used to be a complex of three power stations – Ferrybridge ‘A’, ‘B’ and ‘C’ – all of which received their coal by water; in the case of the ‘C’ station this used an updated 1960s version of the ‘Tom Pudding’ system of tugs and unpowered barges that had been pioneered a century earlier, with the barges lifted bodily and cargo tipped onto the conveyors by a giant hoist. At one time this system was delivering more than 1 million tonnes a year; but deliveries by water ended in the late 1990s, the power station shut in 2016, and it has since been demolished.

A flood lock takes the navigation channel out of the River Aire – and for boats continuing down the main line to Goole, this is the last they’ll see of the river, as the changes to the waterway from here on have been rather more drastic. This is the start of the Knottingley and Goole Canal, a completely artificial channel almost 19 miles long, opened in 1826, which bypassed the entire eastern lower reaches of the River Aire and provided a reliable non-tidal and higher capacity route to the Ouse via the new port of Goole.

A long and relatively narrow (at least for a waterway capable of carrying 500-tonne barges) cutting leads through Knottingley, where the navigation divides. The main line bears right for Goole, while a branch canal continues straight ahead. We’ll first take this branch, which forms an alternative route to the River Ouse at Selby. For its first few miles it rejoins the River Aire, and it gives us an impression of what much of the Aire & Calder Navigation must have been like in its earlier years, before all the straightenings, enlargements, and bypassing of river sections. It’s a winding, relatively narrow river, with some tight bends; the two locks are of more familiar dimensions to us canal boaters, being about 78ft by 16ft, and manually operated.

Attractive flowers on the towpath in Knottingley

Passing the village of Beal (where visitor moorings allow access to the nearby pub) the Aire reaches West Haddlesey (also with a pub), where the navigation leaves the river via a flood lock. From here on, the original route via the tidal Aire is no longer navigable, and we join the start of the Selby Canal, the product of an earlier improvement scheme, opened in 1778 to bypass the tricky tidal reaches of the Aire. Its five miles run through quiet countryside before entering Selby’s industrial outskirts to arrive at the town’s basin. There are visitor moorings to explore the town with its historic abbey, market and shops. From here a tidal lock connects to the Ouse for the journey upstream to York and Ripon or downstream to the Yorkshire Derwent and Pocklington Canal, Goole, and Trent Falls – boaters are advised not to undertake these tidal trips without appropriate preparation and suitably equipped craft.

Returning to Knottingley, we’ll now follow the main line eastwards: it’s a wide, straight waterway, heading east past Kellingley (where the colliery once despatched a 500-tonne train of loaded barges to Ferrybridge every hour), Eggborough, Heck and Pollington villages. Whitley and Pollington locks are huge – they were enlarged to take a tug and 19 ‘Tom Puddings’ totalling about 440ft length in one single locking.

At Southfield Junction the New Junction Canal branches off to the south. Built jointly by the A&C and Sheffield & South Yorkshire Navigation companies, it links their two waterways together with five miles of wide, deep and dead straight waterway. But if that makes it sound less-than-exciting, don’t be put off: as well as forming a useful link it has some interesting features – lift bridges and swing bridges, a lock, and aqueducts over the River Went and River Don.

It ends at Bramwith Junction: turn left for Thorne and (if your boat will fit the short Thorne Lock) Keadby and the tidal Trent; or turn right for Doncaster, Rotherham and (again, subject to boat length) Sheffield.

Returning to Southfield Junction, we’re now on the final length of the A&C main line, heading eastwards alongside the tidal reaches of the River Don, past Rawcliffe Bridge village to reach Goole. A railway bridge marks our arrival in the town, and there are visitor moorings by the sanitary station. Beyond there, the Canal & River Trust’s jurisdiction hands over to the Port of Goole: it’s still a busy commercial port (albeit little of the goods continues inland by water these days) with plenty of freight ships and interesting to walk around.

But don’t continue into the port by water unless you have contacted the port authority – usually this will be for boats (in particular longer craft for which this is the most practicable route) making the adventurous tidal passage to the Trent, for which the appropriate precautions should be taken.

The Tom Pudding Hoist

The Tom Pudding Hoist

While you’re in Goole, take a look at the last of the five hoists which until 1986 lifted 20ft by 15ft ‘Tom Pudding’ compartment boats out of the water and tipped them over, emptying their cargo of 40 tons of coal down a chute into a waiting ship. It isn’t open to the public, but you can get a good view and imagine it at work.

Sadly the small but interesting waterways museum, which told the story of the trade on the Aire & Calder and the ‘Tom Pudding’ system of tugs with indoor exhibits and surviving craft, closed down a few years ago. But you can still see the boat hoist which formed part of this fascinating aspect of the long history of this rather different waterway. .

As featured in the January 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the January 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here