Martin Ludgate heads for South Wales’s Swansea Canal restoration and finds that there’s a lot going on – and it all centres around the strangely-named ‘Hidden Lock’…

In October 2023, an opening celebration took place on the Swansea Canal at Clydach. In what the Swansea Canal Society described as a “major milestone” in its work to regenerate the canal, and following several years’ work by volunteers and other supporters, a short formerly infilled section of channel was opened to form a mooring basin, along with a launching ramp for canoeists and a bywash channel to maintain canal water levels.

A significant opening

Now, some of us with longstanding experience of the great waterway restoration success stories of the past – the trans-Pennine canals, the Kennet & Avon and so on – might be wondering just a little bit (and I’ll admit that I was!) if using expressions like “major milestone” might be over-egging what sounds like a fairly modest reopening. But having visited the canal, I now think we would be wrong to take that view…

Firstly, the work itself is significant: this short length of canal including Lock 7 (which now seems to be universally known as “The Hidden Lock”!) was completely buried under a local council highways depot, and this blockage formed a barrier between two surviving sections of canal. And although work hasn’t yet moved on to digging out the lock, the re-creation of the former bywash channel and the construction of the new basin has involved significant work, both by a helpful local builder and the Society’s volunteers. Channel walls have been rebuilt in concrete below water level and in stone above; use of stone and old ironworks slag, much of it already on site, has helped reduce the need of transporting materials; a ‘green corridor’ is being planted on the offside.

It’s also succeeded in attracting funding grants – from the Welsh Government’s Brilliant Basics fund and Transforming Towns programme, and from Swansea Council’s economic recovery fund – which have set useful precedents for the future.

The next step forward

And crucially, it will lead directly to the next stage of the restoration. Already the bywash channel has been completed to the point where it can take the entire flow of water down the canal, allowing the lock itself to be uncovered and restored. This is where an unexpected bit of foresight helps: the engineer involved in infilling it back in the 1970s thought it might just be worth saving for the future, and therefore made a point of preserving as much as possible of the lock chamber when burying it. There’s been some damage since as a result of a (now demolished) building on top, but it’s still largely intact.

Restoring the lock will still have a significant cost – but the latest good news is that since the October opening celebration, the Canal Society has been awarded no less than £967,000 from the UK Government’s Shared Prosperity Fund. This will pay to uncover the site (including dealing with the ground contamination that’s an inevitable issue when working with the ex-industrial land typical of this area) and restore the lock to navigable standard complete with gates, connected to the canal on either side. Work is expected to get underway soon, as the cash will need to be spent within a year.

So what will that give us in terms of restored navigable waterway? While I was there, I took a look along the canal in both directions from the lock site to find out – and you can too: the towpath is walkable and cyclable for some distance in both directions.

Going first in the uphill (north eastward) direction, a well-maintained restored length of channel leads past Coed Gwilym Park and Clydach Heritage Centre, base for canoeing and other water activities. Another mile of attractive tree-lined navigable canal, with back gardens leading down to the waterside on the left and land dropping away to the River Tawe on the right, leads to the two Trebanos Locks. The lock chambers have already been largely restored, and just need gates to put them back in operation. Another half mile of channel continues above the locks, coming to an end at the start of an infilled (but unobstructed) length alongside playing fields. Two former locks are buried on this length.

The new canoe launch point at Clydach

Further up the valley?

Well-preserved length of canal in Pontardawe, unfortunately surrounded by low-level unnavigable road crossings

This brings us to Pontardawe, and to the first really major obstruction to navigation since leaving Clydach: the A474 crosses on an embankment with the water channel culverted under it (although a pedestrian underpass looks temptingly close to navigable dimensions!)

Beyond, an aqueduct spans the Upper Clydach River, followed by two more serious obstacles to restoration in the form of low-level bridges carrying Herbert Street and Holly Street. “The killer is Pontardawe”, as SCS’s John Gwalter puts it – but then suggests that it might not be quite the show-stopper that it appears: could a lowering of the water level provide just enough headroom under the first bridge, while still leaving adequate water depth over the aqueduct? And would closing the second bridge to traffic and replacing it with a higher footbridge be a possibility? He accepts that some serious negotiations would be needed – but the reward would be re-connection to another unobstructed length of channel.

This continues northeast along the side of the valley bottom, an increasingly wooded length leading via surviving stone hump-backed bridges to the next two locks at Ynysmeudwy, both with stone chambers remaining largely intact.

Ynysmeudwy Locks survive in restorable condition

How far can you go?

Even with the optimism typical of canal restorers, John Gwalter doesn’t see restoration going much beyond there. A new terminus could be created – there’s a site that might make a mooring basin and canal centre – but beyond, a low-level culverted main road bridge, followed by a length preserved as a nature reserve, leads to Godre’r-Graig, beyond which the modern main road up the valley has encroached on the canal line – you can still see parts of locks by the roadside.

This is a shame, because just a couple of miles further on, the intact and impressive three-arch Twrch Aqueduct, crossing another side-stream feeding the Tawe, would be a good destination for a restored canal. But although, as canal restorers are wont to say the length leading to it is “better than some canals being restored elsewhere”, that’s probably hoping for too much. Beyond there, even more of the final section of the canal to its original terminus at Abercraf has been lost to road improvement schemes since it closed.

But having explored the upper lengths, let’s return to Clydach and look the other way, south westward towards Swansea.

Extending down the valley

Below the ‘Hidden Lock’, the canal continues as a clear channel for another quarter mile to Lock 6, variously known as Clydach Lower Lock or Mond Lock. It’s in decent condition and scheduled to follow on as the next lock to be restored. A further half mile of canal leads to the Lower Clydach Aqueduct, an unusual construction incorporating overflow weirs into both sides of the structure – and then, a few yards beyond, the canal comes to a stop with the channel beyond filled in.

Right by the end, a building is currently under construction: this is to be a new canal centre, being built with support from the same grants from the Welsh Assembly, local authorities and others. It will host events, school visits, provide a workshop and store for the Canal Society, and in due course function as the base for a trip-boat operation on the restored canal.

Once the Hidden Lock and Mond Lock are restored, a boat trip operation based here could have a range of two miles and two locks each way. Completion and re-gating of Trebanos Locks would add another half mile. Ultimately dealing with the blockages in Pontardawe and restoration to Ynysmeudwy might provide some six miles of continuous navigation. But what about going the other way and continuing further towards Swansea?

Next in line for restoration after the Hidden Lock is Mond Lock

Back to Swansea?

On the face of it, reopening more than a short length in this direction would appear even less likely than carrying on up the valley beyond Ynysmeudwy. The first mile is still traceable but dry; however, after that, the final five miles and connection to the Tawe estuary in Swansea have been largely lost to road building, the expansion of the city, and the infilling of the former North Dock.

But in recent years a radical alternative has been proposed: instead of attempting to reopen the original route, a new lock could link the canal to the River Tawe at Clydach. Boats would cross the river and continue on a new length of waterway which would continue on the opposite (southeast) side of the river, making use of existing watercourses including a lake and the Nant-y-fendrod stream as well as new sections of canal, before rejoining the Tawe in its lower reaches, where it already has adequate navigable depth, for the last couple of miles into Swansea.

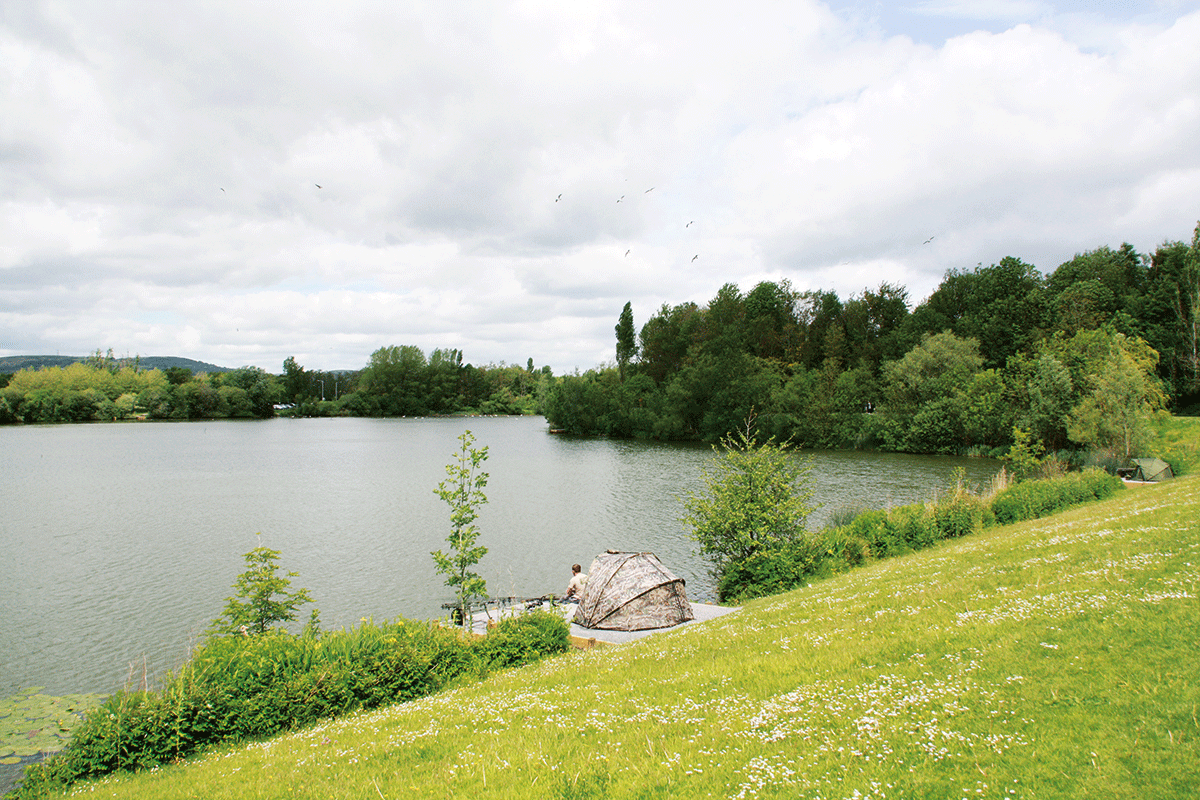

For the future: this lake could form part of an alternative route for the canal from Clydach to Swansea

And then where?

Finally, in a proposal being promoted as the Swansea Bay Inland Waterway, a new link could connect the Tawe near the tidal barrage to the Eastern Docks, and a second new connection could lead from the docks to the Tennant Canal.

This survives largely intact thanks to its function as an industrial water supply after it closed to boats. It’s already being proposed for reopening, along with the Neath Canal which it meets at Aberdulais, by the Neath & Tennant Canals Trust. Ultimately, the three restored canals linked together could create a connected local navigable network of 35 miles or so.

Does that sound far-fetched? Well, so did most canal restoration schemes to begin with…

As featured in the February 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the February 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here