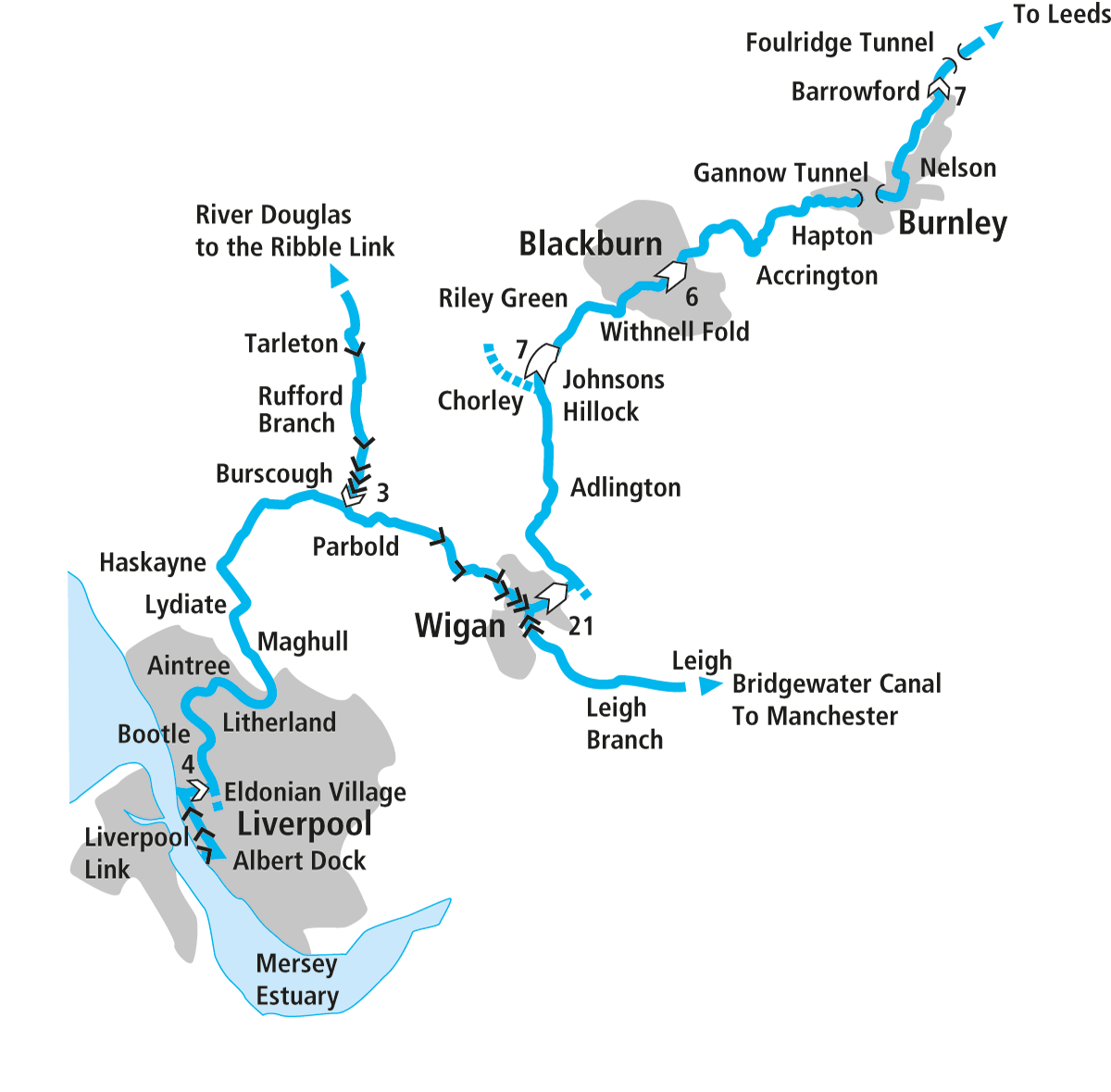

In the first part of our guide to Britain’s longest canal built as a single entity, we explore its contrasting Lancashire lengths: the meandering reaches crossing the coastal plain to Liverpool, and the steep climb from Wigan into the Pennines

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

When planning an article describing the 127¼-mile trans-Pennine route of Britain’s longest single canal, it might seem like you have two obvious choices: either start at Liverpool and head for Leeds, or vice versa. And as the last time we covered it several years ago we began at the Yorkshire end, it might seem like starting at Liverpool would be the obvious choice this time around.

When planning an article describing the 127¼-mile trans-Pennine route of Britain’s longest single canal, it might seem like you have two obvious choices: either start at Liverpool and head for Leeds, or vice versa. And as the last time we covered it several years ago we began at the Yorkshire end, it might seem like starting at Liverpool would be the obvious choice this time around.

But although it would have been the origin of plenty of the canal’s trade in its working days, very few of today’s inland boaters begin their journey along the L&L by joining the canal in Liverpool. That’s because to get there by any other route means cruising the Manchester Ship Canal and crossing the Mersey Estuary – which is an adventurous trip requiring a suitably equipped and reliable craft, experienced crew, knowledge of the waters and a certain amount of paperwork to satisfy the Ship Canal’s requirements.

In practice, the majority of boaters arriving on the Lancashire lengths of the Leeds & Liverpool from elsewhere on the waterways network do so via the canal’s Leigh Branch, which provides a link to the Bridgewater Canal. So that’s what we’ll do.

From the Bridgewater Canal’s main Runcorn to Manchester line, which forms part of the popular Cheshire Ring circuit of waterways, boats turn off north westwards at Waters Meeting junction in Stretford, taking the Bridgewater Canal’s Stretford & Leigh Branch. As it traverses the western suburbs of Manchester, it crosses the Manchester Ship Canal via the unique Barton Swing Aqueduct, passes the historic Worsley Delph, where a network of tunnels took boats right into the Duke of Bridgewater’s coal mines, leaves the built-up area behind for a couple of miles as it passes the mining museum at Astley, and arrives in the former coal mining and mill town of Leigh.

Here the canal makes an end-to-end junction with the Leigh Branch of the Leeds & Liverpool Canal: signs at Leigh Bridge welcome boaters to the Leeds & Liverpool Canal, as well as pointing out (for the benefit of Bridgewater-based boats) that they’ll need a Canal & River Trust licence. This is because the Bridgewater isn’t part of the CRT system (being owned by the Manchester Ship Canal’s owners Peel Ports); for CRT-licensed boats using it to get to the Leeds & Liverpool, there are reciprocal arrangements allowing seven days free use of the Bridgewater (plus another three on the way back if you return this way) within 28 days.

Other than that, there isn’t any real change to the waterway. It’s still a wide-beam canal running through surroundings getting gradually more rural as it continues northwest. When I say ‘rural’, that’s how they appear now; however, there are plenty of signs that this was once a coal mining area. It’s been estimated that over 90 feet thickness of coal seams has been extracted from parts of this area, resulting in a great deal of subsidence and the creation of ‘flashes’ – lakes resulting from the flooding of the sunken land. With the disappearance of industry, several of the lakes and their increasingly wooded surroundings are now nature reserves. Another sign of the changes is that you will cruise through the gateless chamber of one of two locks on this section which were made redundant by the changes in ground levels. A rarity for the Leeds & Liverpool is a liftbridge at Plank Lane, carrying a road and electrically operated using your CRT ‘Watermate’ (sanitary station) key.

It stands to reason that the abolition of two locks due to mining subsidence would need to be balanced by the addition of two more locks elsewhere on the canal – and sure enough, on the approach to Wigan, boats encounter the two Poolstock Locks, added during the 20th Century, climbing towards the town centre. Unlike some locks on the canal, these are large enough to take a pair of full-length 72ft narrowboats. You’ll notice a slight oddity at one lock: the gates are pulled open by a winch and chain attached to the balance beam.

In Wigan, the Leigh Branch ends at a T-junction with the canal’s main line: turn left for Liverpool or right for Leeds. We’ll go westwards first, and we begin by descending two locks: these, and indeed all the locks from here to Liverpool, were originally built to take boats 62ft by 14ft (to match the size of locks on the earlier River Douglas Navigation) but were soon extended to 72ft to allow full-length working narrowboats from the narrow canals in the Manchester area to reach Liverpool. They take the canal into an area of the town which used to be the site of several museums founded in the 1980s and recalling Wigan’s industrial heritage. Sadly, more recently there have been closures, but the historic Trencherfield Mill engine is still in working order although as of early 2024 temporarily closed to the public pending building repairs. This area is convenient for mooring for the town’s shops and other facilities.

Trencherfield Mill Engine

Trencherfield Mill Engine

Built over 100 years ago, this massive industrial steam engine powered all the machinery in the impressively large canalside mill in Wigan, producing over 2500 horsepower. Since the demise of the textile industry, the engine has been fully restored to its former glory and is open to the public and in operation on certain dates.

Just beyond the mill, the canal takes a sharp left turn to pass the famous Wigan Pier – a name that’s been variously a music hall joke and the inspiration for the title of George Orwell’s book The Road to Wigan Pier, but which is now used to refer to a re-creation of a former coal loading point where railway wagons were tipped up to empty the coal into boats. From there the canal heads westwards through an industrial area, while a couple more locks continue the slow descent. These locks too show signs of changes over the year: Pagefield Lock was added, Crooke Lock was abolished, Hell Meadow Lock simply lost its ‘H’ and became Ell Meadow. It was clearly a busy length, as most of the locks were once duplicated – at Appley Locks there was a choice of one deep lock or two shallow ones, but only the deep lock is operational now. And at the formerly paired Dean Locks, if you look carefully you might be able to make out where a third lock once provided a link to the earlier River Douglas before it was superseded by the opening of the length of canal leading to Wigan.

Meanwhile, the industrial surroundings have been left behind for the more rural Douglas Valley, which in turn gives way to the flat Lancashire coastal plain – and there are no more locks on the main line all the way to Liverpool. But the canal makes up for it with the appearance of the first swing bridges, which are a characteristic Leeds & Liverpool Canal feature. Some are left open, others you will need to open – and you may need your Watermate key.

Swing bridges are a feature of the Leeds & Liverpool, including this example east of Burscough

Approaching Burscough, the Rufford Branch leads off on the right: once a quiet rural backwater leading to a little-used connection to the tidal River Douglas at Tarleton, it gained a new importance in 2001 with the opening of the Ribble Link. This new navigation based on the Savick Brook created a connection to the Lancaster Canal, making that waterway part of the national navigable network for the first time in its history. If you want to make the tidal passage to the Lancaster you’ll need to book it with CRT, and once again it’s a trip that needs a suitably capable and well-equipped craft, experience and knowledge of the waters. But the Rufford Branch is worth exploring for its own sake, as it descends a series of seven locks (which were also built for 62ft by 14ft boats but never lengthened, so longer craft won’t fit), initially closely spaced but then spreading out as its reed-fringed channel passes through quiet countryside to Rufford and Tarleton.

Typical quiet countryside surrounds Lock 5 on the Rufford Branch

Burscough is a useful town with shops, pubs, and an artisan market by the wharf if you happen to be there on the first or third Sunday of the month. This is the last place of any real size before Liverpool, as the next few miles meander through quiet open countryside with just the odd small village and the occasional swing bridge to provide some exercise. It is, however, surprisingly well-provided with canalside pubs.

Some expansive meanderings (the canal heads in all directions from northwest to southeast) eventually see it arriving at the start of the Liverpool area with Lydiate and Maghull, and then there’s just a brief rural interlude before the continuous built-up area begins. Skirting the Grand National course at Aintree (this is the canal that gives its name to the racecourse’s ‘Canal Turn’) the canal winds through the residential areas of Litherland and Bootle, then the final industrial districts on the way into the city centre. The original terminal basins have long since been filled in, but the area around it has been regenerated in recent decades to create the Eldonian Village, surrounding a new canal terminus a little short of the original end. But for most boaters who’ve made it this far, the objective is the four-lock Stanley Dock Branch and the new Liverpool Link Navigation leading to the Albert Dock complex and visitor moorings in the heart of the old docks. And we’ve covered that in our Cruise Guide Extra article on the following pages.

Swing bridge near Maghull, on the approach to Liverpool

We’ll now retrace our steps to Wigan, and take the third direction – the main line heading east over the Pennines.

For a trans-Pennine canal, it might seem like we’ve seen surprisingly few locks so far – just six on the main line of the canal between Liverpool and Wigan. But all that changes immediately at Wigan. In addition to the two locks west of the junction, a mighty flight of 21 locks climbs steeply out of the town. Mining subsidence has taken its toll here too, with the locks varying between shallow and deep. Of rather more importance to boaters is their length. Unlike those west of Wigan and on the Leigh Branch, the locks from Wigan to Manchester were never lengthened from their original dimensions, so they’re limited to 62ft by 14ft craft (or slightly longer for a narrowboat).

Volunteer lock keepers assist boaters climbing the Wigan flight

They’re all fitted with anti-vandal locks opened by a CRT ‘handcuff’ lock key (that’s the T-shaped one), and there are a couple of unusual ones with gates opened by winch or by a gear engaging with a quadrant-shaped rack. They might not have the impressive (perhaps daunting) sight of many locks climbing one after another up the hillside (like Hatton or Devizes), but there’s no real let-up. However, the reward for your hard work once you reach the top lock is a level pound almost ten miles long, leading from there via Adlington and Chorley to the next flight at Johnson’s Hillock. Note the sharp right-angle left turn immediately above the top Wigan lock with what looks like an abandoned arm going off to the right, and also another overgrown old arm which turns off just below the bottom lock at Johnson’s Hillock: these (together with the traditional name of the Lancaster Pond for this section) are hints of a rather complicated history…

At the same time as the L&L was being planned, so too was the Lancaster Canal which was to run north-south all the way from Kendal via Lancaster, Preston and Chorley to Westhoughton, east of Wigan. But the money ran out with only two isolated lengths competed – one from Kendal to Preston, and the other from Walton (north west of Johnson’s Hillock) to near Wigan (and a few miles short of Westhoughton). This southern section ran roughly parallel to the route being planned for the Leeds & Liverpool Canal, so the two companies came to an agreement that the L&L would alter its plans so that they would save money by sharing the length from Wigan Top Lock to Johnson’s Hillock. The Lancaster only ever managed to link this to its main northern length by building a ‘temporary’ connecting horse-tramway; this was abandoned many years ago, and the shared section of canal became part of the Leeds & Liverpool – with the remains of the abandoned arms above Wigan and below Johnson’s Hillock surviving as reminders of the Lancaster’s original plans.

Attractive wooded stretch above Wigan Locks

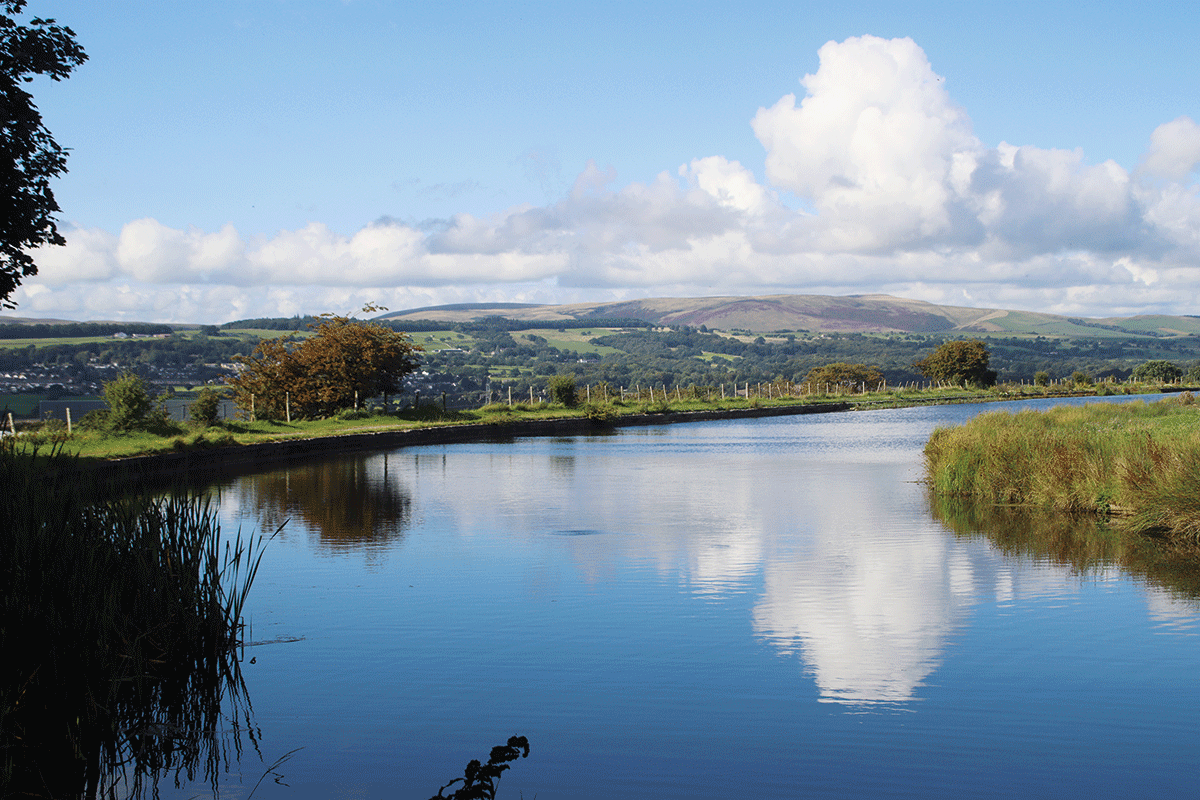

Above the seven Johnson’s Hillock locks is another lengthy level pound as the canal clings to the contours of the hillside. Open countryside gives way to housing and industry as the canal approaches the first of two big Lancashire mill towns: Bolton. A steep flight of locks climbs through the town’s outskirts, with the centre a little way to the north. The canal now embarks on an even longer level pound, winding this way and that as it follows the contours of the valley side high above the Lancashire Calder, with expansive views northwards to some impressive hills, leaving no doubts that we really are on a trans-Pennine route now.

From the long level pound between Blackburn and Barrowford there are splendid views across the Calder Valley to the hills beyond

Look out for a special milepost installed in recent times – it’s based on a more ornate version of the traditional Leeds & Liverpool design that you can spot every mile, but this one marks the exact mid-point of its 127¼-mile length. Skirting the towns of Rishton and Church, the canal continues eastwards: at times the peace is disturbed by the proximity of the M65 motorway, but it does provide the novelty of not one but two places where the canal spans the motorway on modern concrete aqueducts.

Historic warehouses forming part of the Weavers’ Triangle area in Burnley

Arrival in the second big mill town, Burnley, is marked by the canal’s first tunnel. Make sure there’s nothing coming before entering the 559-yard Gannow Tunnel, as wide-beam craft regularly use this canal, so even if you’re in a narrowboat you can’t guarantee there will be room to pass. The tunnel emerges into Burnley’s built up area, entering the canalside Weavers’ Triangle district of the town which is now recognised and protected for its historic industrial buildings. At Finsley Gate the canal takes a sharp left turn and launches out onto the ‘Straight Mile’ – a long, straight, wide, high embankment reaching for not far short of a mile, giving views over the town’s rooftops – and easy access to the town centre.

Pendle Heritage Centre

Pendle Heritage Centre

Visit the heritage centre in Barrowford to learn about the heritage of Pendle Hill and Pendle Forest, find out about the Pendle Witches, and enjoy the 18th century walled kitchen garden, garden museum and tea room

Skirting Brierfield and Nelson towns, the canal finally shakes off the last of the industrial and urban surroundings as it approaches Barrowford Locks – the end of a remarkably long level pound of almost 25 miles since Blackburn. The seven locks climb through rural surroundings (albeit interrupted for one last time by the M65) to reach the canal’s summit level. Foulridge Tunnel at 1640 yards is long enough to justify installation of traffic lights at each end to control one-way traffic. Its other distinction is the legend that a cow once fell in the canal and swam right through the tunnel!

Foulridge Reservoirs

Foulridge Reservoirs

Follow the old tunnel path that the boat horses used to walk over the top of Foulridge Tunnel (while their boat was ‘legged’ through the towpath-less tunnel) for a fine walk over the hill top with some excellent views of a part of the canal’s heritage that you won’t see from your boat: some of the reservoirs built to keep this thirsty canal topped up with water

It emerges into Foulridge village and the beginning of the really attractive Pennine lengths of the canal. A sign soon indicates that we are passing from Lancashire into Yorkshire. No mere county boundary this; it’s actually described as a ‘border’, indicating how seriously Roses folk take such things!

It seems a good place to stop for now: having left Red Rose country behind us we’ll follow the canal down through White Rose country to Leeds next month.

As featured in the April 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the April 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here