Is it possible to make the South Oxford Canal’s lift bridges easier for single-handed boaters, without spoiling their heritage value? CRT thinks it’s found a way…

Think of the South Oxford Canal, particularly the section running south from Banbury down the Cherwell Valley to the Thames in Oxford, and one of the images you’ll probably come up with is a lift bridge. Those traditional wooden drawbridges with their rising balance beams, operated by the simple method of hauling the beams down using the chain provided, are a characteristic feature of this canal. And while opening bridges are a feature of many of our canals, none were built in the same style as the Oxford ones. They’re just simple, attractive, distinctive and in keeping with the scale of an early narrow canal. The idea of the South Oxford without its lift bridges would be unthinkable (not to mention probably impossible to achieve, given that no fewer than 19 of them are listed by Historic England).

A problem for single-handers

Well, that’s one way of looking at them. Single-handed boaters might have a rather less charitable view. Like all opening bridges, they generally open from the offside (the non-towpath side) of the canal, for good reasons – in horse boating days, it gave the horse a clear run past the bridge, without having to detach the towline. But with the offside bank usually in private ownership, the landing stages provided for operating the bridge are on the towpath side. So, having tied their boat up, jumped off and walked up to the bridge, crossed the canal, and pulled down on the chain to open the bridge, how does the single-hander get back on their boat to bring it through? Not to mention how do you stop the not always well-balanced bridge from descending as your boat passes under.

Yes, there are ways round it – we once dedicated an entire magazine article to methods of single-handing swing bridges and lift bridges, from hauling the boat through from the bridge using the bow rope, to lifting it from the ‘wrong’ (ie towpath) side of the canal and leaving it propped up using a ‘Banbury stick’ (a short boat-pole) as the boat went under it. At least we didn’t actually advocate one version of this method, in which one would yank the stick out with a rope as one passed on the boat, leaving the bridge to come down “with a satisfying kerwallop!” But none of these methods are particularly satisfactory.

As far as CRT is concerned it’s not just something that’s ‘nice to have’: it’s one of the Trust’s Minimum Safety Standards (first issued by CRT’s predecessors British Waterways over a decade ago) that navigation structures should be able to be operated safely by single handed boaters. And there’s no easy way of modifying them to make operation easier or safer. CRT has tried weighting the balance beams with steel weights or a sand box so that the bridges stay open, and providing a locking mechanism to hold them shut. But even trying to get the balance right so that they will stay open or closed isn’t easy – as the Canal & River Trust’s engineer Neil Owen explains to me, just the effect of the seasonal wetting and drying-out of the timbers is enough to upset the balance of a bridge, making it tend to drift open (or shut). So, does he have an answer?

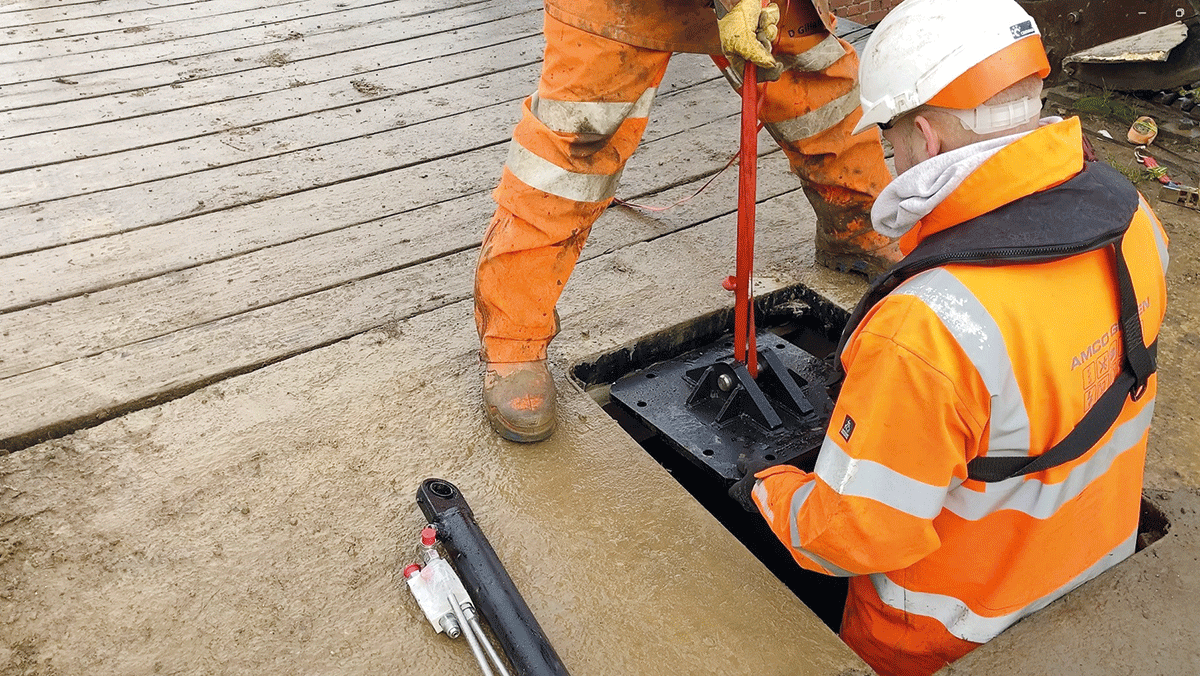

Lowering the steel baseplate carrying the mounting for the hydraulic ram into place under the bridge abutment

Has CRT found a solution?

Well, that’s why we’re on the towpath by Bridge 193, Chisnell Lift Bridge, between Aynho and Somerton. We’re here to see a demonstration of a modification that CRT has developed which the Trust reckons will solve the problem of making the bridges operable by single-handed boaters, without spoiling their historic appearance.

Having considered and rejected the idea of electric operation – not least because (as is well demonstrated by this particular bridge) many of the sites are a long way from the nearest electricity supply, and it would be expensive to run cables out to them – the Trust has instead gone for hydraulic operation, manually operated from the towpath side of the canal. Not only does this avoid the need for an electricity supply, but CRT reckons it’s also more ‘fail-safe’ in an emergency – if you stop winding, it stops. Neil Owen says that the hydraulic bridge already installed near Banbury Town Lock has been in operation for quite some years and is tried and tested – and it would be simple to revert to manual operation if there’s a failure with the hydraulics. As for the actual hydraulic gear, this will be familiar to boaters – especially those who’ve been around for a while…

That’s right: those cylindrical windlass-operated mechanisms which were once seen by the then British Waterways (and cursed by many boaters) as being the future standard units for operating all lock paddles.

Derided in those non-PC times as “granny paddles” which would reduce the fascination of the waterways network to dull uniformity (not to mention also precluding the rapid dropping of paddles in an emergency) in the name of making it marginally easier for the elderly and infirm to work the locks, they were abandoned as a future national standard, but survive on a few locks and have since found a niche as a method of opening lift bridges in a few places.

But would it be possible to make them unobtrusive enough for the Oxford’s heritage bridges? CRT thinks so.

The hydraulic ram as seen when the bridge is raised

Installing the hydraulic system

The main visible evidence of the conversion of Bridge 193 is the pedestal by the towpath carrying the operating gear. Rather surprisingly to somebody who recalls the anti-hydraulics feeling among 1980s boaters, CRT now sees the cylindrical hydraulic units as something approaching ‘heritage’ in their own right – and something to be copied today as a nod to the past (or in one case, unearthed in a CRT store and restored by CRT’s Newbury volunteer team), rather than using more modern-looking units. After all, as Neil Owen points out, the original 1970s hydraulics are older now than the ‘modern’ 1930s Hamm Baker paddle gear of the northern Grand Union was in the 1970s. I grudgingly accept that he may have a point…

The rest of the modifications are less obvious. A typical road manhole cover, in the abutment on the non-towpath side, hides a pit that was excavated to house the hydraulic ram that lifts the bridge. The ram itself is hidden under the bridge: as the bridge deck rises, you can see the relatively small operating rod emerging from a slot cut in the centre of the bridge abutments, with its outer end attached to the deck. The other parts – the connecting hydraulic hoses and fittings which link it to the operating pedestal – are underground, buried under the canal bed and banks.

There’s been some effort to work with CRT heritage advisor Phil Emery to minimise the disturbance to the historic fabric: for example, where cutting the slot for the hydraulic ram in the centre of the abutment would mean cutting through original coping stones, it can be shifted to the left or right to avoid this.I try operating it: CRT reckons it’s a good balance between being either too heavy or too many turns. It’s 26 turns to open it, and 15 to shut it. Sure, a lot slower than simply dangling on a chain, but not too bad.

The conversion programme

This is the second bridge to be dealt with in a programme of seven, targeting those which see the most use because they are generally left in the ‘down’ position – either they carry public footpaths, or they’re regularly used by farmers. Already Bridge 231 above Duke’s Lock has been done. Bridge 219 at Shipton-on-Cherwell was due to be started as soon as 319 was finished, while 233 and 234 near Wolvercote would follow in early spring, then bridge 171 near Banbury and finally 215 near Kirtlington, which suffered an abutment failure but which the landowner needs for access.The operation has had to fit in with various routine maintenance and repair work on the bridges – for example a typical wooden bridge deck needs replacing every 25 years; there are also repairs to abutments – some are such a patchwork of stonework and various ages of brick that it’s hard to see what if anything is original.

The work has been done by Amco, CRT’s omnibus contractors for electrical and mechanical work for this region: in the past, a single engineering firm (most recently Kier) was appointed as omnibus contractor for all work, but under the recent retendering it’s now split between a number of different contractors doing different types of work and different regions. However, if that sounds like a way of over-complicating matters, CRT reckons that it isn’t necessarily the case: in this project Amco have the expertise to do it with their own in-house staff; Kier would have almost certainly have subcontracted it to someone like Amco.

As regards funding the work, which might raise some eyebrows given CRT’s well-reported financial issues as a result of inflation reducing the value of its public grants (and the threat of much worse when the contract ends in 2027), the money (in the region of £650,000 for the first four bridges) has largely come from the People’s Postcode Lottery, whose players have contributed over £18m (much of it to projects which would have struggled to get funded from CRT’s main maintenance budgets) in the 12 years that it’s been supporting CRT.

So, will they need more maintaining than when they were manually opened? CRT reckons they “aren’t high maintenance”: the only moving parts are the hydraulic pump, hoses, valves and cylinder – it will be necessary to do an annual check on them, but the Trust doesn’t see them needing the amount of maintenance work that electric ones would need.

Neil Owen reported that the programme had largely gone to plan so far. In the particular case of Bridge 319, matters were slightly complicated by the remote site meaning materials and equipment had to come in by boat; the only major hitch on any of the bridges was that in one case while the deck had been removed to one side, some members of the public used it to light a barbecue on!

So once these seven bridges are converted to hydraulic operation, will the rest of the canal’s lift bridges follow? No, that isn’t currently the plan. The remainder are either ‘standing monuments’ which are never closed at all, or are normally left in the ‘up’ position and rarely used. They will stay manually operated.

So, we won’t completely lose the traditional Oxford bridge in its authentic 18th century manual form – we just won’t normally have to operate any of them.

Bridge 233 near Wolvercote is one of the next on the list

Why lift bridges?

Why did the Oxford Canal Company choose to use liftbridges for so many farm crossings on the southern length of the canal? It’s reckoned to be because they were cheaper to build than brick or stone bridges – which would explain them getting more common towards the southern end. The initial funds ran out when the canal reached Banbury, and it took some time to raise the cash to continue to the Thames.

This would fit in with a couple of other cost-cutting measures adopted as construction proceeded southwards: the locks were built with single gates at both ends, rather than the more usual arrangement of paired bottom gates adopted on the northern section. The locks were also originally built with ‘letterbox’ overflow slots which carry surplus water into the lock chamber via the upper ground paddle culverts, rather than separate overflow bywash channels around the locks. And CRT’s engineers told Canal Boat that in their experience the lock chambers were shallower too: not enough to reduce the load that boats could carry, but a slight inconvenience in that the bottom gate cills aren’t raised as high above the lock floor as normal, so any detritus in the lock is more likely to stop the gates closing properly.

All of these measures could be seen as false economies in the long term, but to the cash-strapped canal company struggling to open its canal in the 1780, there was no alternative. And at least in the case of the bridges it’s left us with a picturesque feature, although the working boat crews probably cursed them – especially when they were rather more frequent.

Originally there were no fewer than 38 lift bridges just on the length south of Banbury (that’s almost as many as the 41 brick and stone bridges on this section) plus several more further north. Over the years, many have disappeared as they have fallen out of use or been replaced by fixed bridges. Today just 20 remain, 18 of them south of Banbury.

As featured in the April 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the April 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here