In the second part of our guide to Britain’s longest canal built as a single entity, we explore its eastern Yorkshire lengths: beginning at the summit, we follow the winding route through remote and scenic Pennine country, followed by the descent into Airedale, passing old mill towns on its way to Leeds.

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

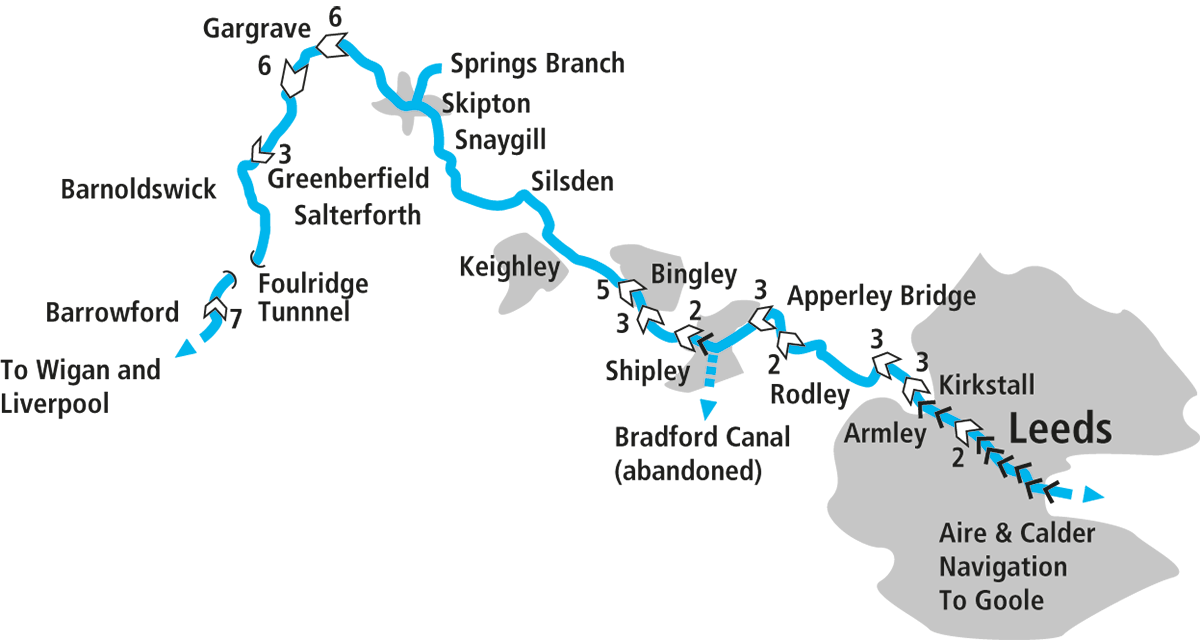

So it’s all downhill now, is it? After all, we finished part one of this guide to Britain’s longest single waterway on a high, both physically and metaphorically, climbing a flight of seven locks as the canal rose into the splendid moorland countryside of the Pennines. We passed through Foulridge Tunnel (which, famously, a cow once swam right through!), crossed the boundary from Lancashire to Yorkshire, and looked forward to the descent down the Aire Valley to Leeds.

The Summit Level

But while it’s true that it’s physically downhill all the way, that’s very much not true in terms of scenery. In fact, if anything, the best is yet to come. The northern part of the summit level is actually a quiet, secluded, often tree-lined length of canal, with a brief industrial interlude as it passes the factories on the edge of the useful town of Barnoldswick. There are a couple of historical quirks on the way: firstly the canalside Anchor pub (see Top Ten Pubs list). It was already in existence when the new canal came through in the 1790s, but found itself at the wrong height, with the towpath passing at first floor level. So the pub’s owners added a new top floor to the building: this became the landlord’s accommodation, the original bedrooms on what was the first floor became today’s bar, the old bar area below it became the cellar, and the original cellar beneath that is now a dark cave with stalactites and stalagmites.

And secondly there was once a canal arm, the Rain Hall Rock Branch, which headed off eastwards through two short tunnels to emerge in a deep cutting leading to the stone quarry which provided much of the trade on this part of the canal. There’s little sign today of the junction, but it’s possible to track down some remains of the arm on foot from Bridge 153 – although much of it has disappeared in recent decades with it being used as a landfill site. Finally, where the summit ends at Greenberfield Locks, there are traces of the original route of the canal, whose two staircase locks were replaced by two of the present set of three separate locks as a water-saving measure on the recommendation of engineer John Rennie.

The tree-lined cuttings and industrial surroundings have been left behind, and the locks are in a fine setting amid open Pennine scenery. Continuing with quirks of the canal’s heritage, they display several examples of its great variety of paddle gear, which is a particular feature of the eastern sections of the canal. Some are opened by lifting a large lever alongside the lock head wall; some by rotating a handle (or using a windlass) on the top of a vertical shaft in a pedestal on the lock-side; some by turning a gearwheel that engages with a toothed rack mounted horizontally across the lock gate.

And a final snippet of waterways history: there was once a proposal to build a canal north from here to Settle, and another from there westwards to Lancaster: even by the standards of the ‘canal mania’ years it was an optimistic idea, however much we might wish it had been built. It would have featured an improbable-sounding 45-lock flight including two seven-lock staircases, as well as a 25-mile level pound leading to the junction above Greenberfield Locks, which at least might have helped to maintain the L&L summit’s sometimes difficult water supplies…

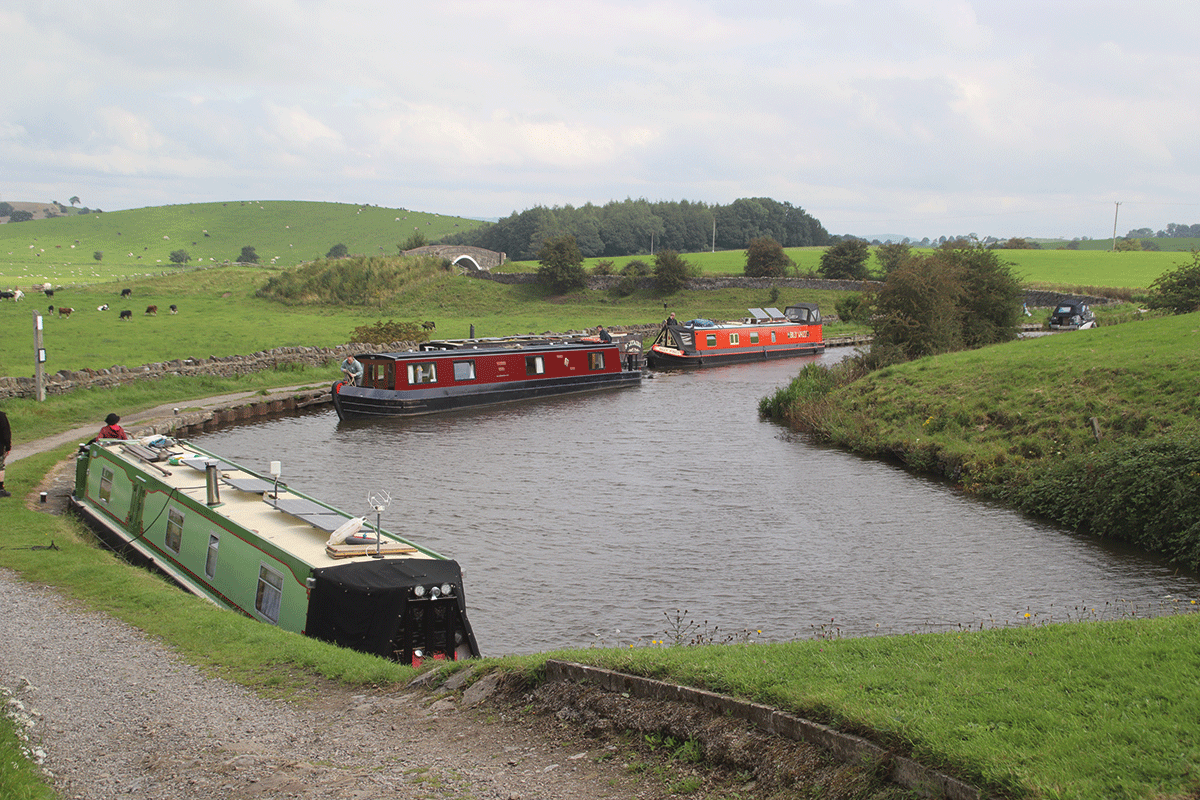

The canal’s zigzagging course below Greenberfield Locks is a sign of what’s to come

Crossing the Pennines

Meanwhile back in the real world, the view from the bottom lock of the canal zigzagging away towards the distant hills gives a good foretaste of perhaps the most spectacularly scenic length of the canal – some might say, of any of the Pennine canals. For six miles it turns this way and that as it skirts the hillsides and valleys, clinging to the contours and providing dramatic upland views at every turn. Other than at East Marton village (notable for its curious double-arched bridge, the result of it being raised to remove a dip in the road) it’s an entirely rural length with few road crossings and just the odd farm for company.

The descent begins in earnest at Bank Newton, where a flight of six closely-spaced locks is followed by six more spread-out ones through Gargrave. Note the small aqueduct in the short gap between the two flights: this is the River Aire, which will keep us company all the way to Leeds as we continue down the Airedale valley. Gargrave is an attractive village with a couple of pubs and useful shops.

We now take a rest from locks, with none in the next 17 miles as the canal sticks to the valley side, but instead we have swing bridges to exercise the crew. These vary between hand-operated farm crossings and electrically powered road bridges, and you may need either a Canal & River Trust ‘Watermate’ (sanitary station) key or a CRT T-handle ‘handcuff’ key to operate them – best take both! Two swing bridges in short succession and a glimpse of a tall mill chimney announce our arrival in Skipton, ‘Gateway to the Dales’, a town with many attractions including the castle, the town woods (a short walk up the canal’s short Springs Branch – don’t try this by boat unless you don’t mind coming out backwards!), the Craven Museum, an annual sheep fair (the town’s name means ‘sheep town’), and a really fine canalside with town centre buildings facing the junction of the branch and the main canal.

Unusual double arched bridge at East Marton

Into the Aire Valley

The canal continues down Airedale, passing through Snaygill, Bradley and Kildwick villages. After a few miles the main road crosses to the far side of the valley, leaving the canal in peace as it runs through Silsden and on to Riddlesden. Look out in Bradley for a monument by a swingbridge. This, together with a simpler, less formal memorial on the towpath nearby, commemorates a sad event of 1943, when seven Polish airmen lost their lives when their aircraft suffered a structural failure during a training mission and crashed by the canal. One of them had been married just three weeks; 64 years later his widow unveiled the memorial.

Stocksbridge and Riddlesden mark the end of the truly rural lengths, as the mill town of Keighley is visible across the valley, and the long level pound comes to an end at the celebrated Bingley Five Rise Locks.

Approaching Skipton from the west

Keighley & Worth Valley Railway

A one-mile walk (or frequent bus service) from Bridge 197 is Keighley Station, where the branch line to Haworth (famous for the Brontë Parsonage Museum) and Oxenhope was saved by enthusiasts after it closed in the 1960s, and now runs heritage steam and diesel train services, as well as the Engine Shed museum and the Carriage Works collection of historic wooden-bodied railway carriages.

A one-mile walk (or frequent bus service) from Bridge 197 is Keighley Station, where the branch line to Haworth (famous for the Brontë Parsonage Museum) and Oxenhope was saved by enthusiasts after it closed in the 1960s, and now runs heritage steam and diesel train services, as well as the Engine Shed museum and the Carriage Works collection of historic wooden-bodied railway carriages.

Staircase Locks

The impressive Bingley Five Rise Locks

This remarkable structure isn’t the longest set of staircase locks in Britain (that honour goes to the eight-rise Neptune’s Staircase on the Caledonian Canal); it isn’t even the only five-rise on the national canal network (there are two more at Foxton); but it’s certainly the steepest, its 12ft deep locks, with their short chambers built for craft up to 62ft long (rather than the 70ft by 7ft narrowboat more typical of the Midlands canals) giving it a gradient of almost 1 in 5. And personally I’d rate it the most impressive, its solidly built stonework climbing up the Aire valley side in five mighty steps. Imagine what an impression it created when it opened in 1774. Well, actually we don’t need to imagine it, because it’s on record that 30,000 people turned out to see the first boat pass through in a respectable 29 minutes. And we very nearly lost it…

The same report by leading canal engineer John Rennie (who seems to have been a bit of a ‘Mr Fixit’, often brought in by canal companies for advice on technical matters) which recommended replacing the two staircase locks at Greenberfield with two singles, also recommended removing the Bingley Five Rise and replacing it with five single locks, to save water. But the need wasn’t quite so urgent (the Greenberfield Locks draw water from the canal’s summit pound, which has always been the hardest to keep topped up), the cost was higher, and the canal company never acted on that recommendation. So the staircase locks remained.

The locks are staffed and operated under supervision of lock keepers, who generally operate to a timetable, alternating between several lockfuls of boats in one direction and several in the opposite direction. Check the CRT website canalrivertrust.org.uk in advance to find out what the current timings are, or you risk a lengthy wait. In winter the hours are shorter, and you’ll need to book in advance.

The Five Rise is the most impressive, but by no means the only set of staircase locks on this canal. Indeed, in the descent from here to Leeds there are more staircase locks than singles, with three pairs and four sets of three. And once you’ve left Bingley you’ll generally be working them on your own. So why did the engineers use so many staircase locks? Well, this was one of the earliest lengths completed (it opened in 1777) and it seems that it wasn’t appreciated in the early years how much of a bottleneck of how wasteful of water they could be, and used them wherever there was a steep change in level to overcome. Some other canals built around the same time also made use of staircase locks – for example the Chesterfield, and to a certain extent the Trent & Mersey (although they were later rebuilt as singles).

Staircase Locks are common on the eastern length of the canal

Saltaire

Created as a ‘model village’ by industrialist Sir Titus Salt to provide better conditions for his workers than the slums of nearby Bradford, Saltaire was built around his textile mill, known as Salt’s Mill, and included streets of workers’ houses, a library, a concert hall, a gymnasium and a park – but no pubs. Today it’s a World Heritage Site, the Mill has been converted to house an art gallery, restaurants and independent shops. And Saltaire does now have a pub!

Created as a ‘model village’ by industrialist Sir Titus Salt to provide better conditions for his workers than the slums of nearby Bradford, Saltaire was built around his textile mill, known as Salt’s Mill, and included streets of workers’ houses, a library, a concert hall, a gymnasium and a park – but no pubs. Today it’s a World Heritage Site, the Mill has been converted to house an art gallery, restaurants and independent shops. And Saltaire does now have a pub!

The approach to Leeds

Dowley Gap Locks are followed by Dowley Gap Aqueduct, and you can appreciate how much the River Aire has grown since we last crossed it before Skipton, as this impressive structure crosses it on seven stone arches (albeit several of them are only needed in floods). Saltaire, a new ‘model town’ created for his workers by industrialist Sir Titus Salt (see inset) is followed by Shipley where the ill-fated Bradford Canal once branched off to the south, as the valley becomes increasingly industrial and built-up as it gets closer to Leeds. There are still quiet, rural lengths of canal, however, as it follows the Aire with the developments keeping back from the riverside. Apperley Bridge and Rodley provide shops and pubs, while locks (or staircases) every mile or so maintain the descent towards Leeds.

The ruins of Kirkstall Abbey can be seen on the north side of the river, before the canal’s surroundings finally become heavily industrial with railway lines accompanying the waterway for the run into the city. The last mile into Leeds city centre has seen great changes in recent years, as old industrial areas have been replaced by modern developments on both sides of the canal – a process which continues.

Lock 2 (Office Lock) opens into a basin area alongside Leeds City railway station with moorings handy for all Leeds’ attractions. It’s a good place to tie up and see the city after your 127¼ mile journey from Liverpool along Britain’s longest single canal, before you pass through the final lock into a very different waterway, the Aire & Calder Navigation.

Kirkstall Abbey

In existence as a Cistercian monastery from the 12th Century until the Dissolution of the Monasteries under King Henry VIII, Kirkstall Abbey is now a picturesque ruin which has been an inspiration to artists including JMW Turner. It is situated in a park not far from the canal, a visitor centre tells its story, and its gatehouse houses a local museum with re-created Victorian streets and community displays.

In existence as a Cistercian monastery from the 12th Century until the Dissolution of the Monasteries under King Henry VIII, Kirkstall Abbey is now a picturesque ruin which has been an inspiration to artists including JMW Turner. It is situated in a park not far from the canal, a visitor centre tells its story, and its gatehouse houses a local museum with re-created Victorian streets and community displays.

The longest canal?

You’ll have seen one or two mentions both in this article and in part one (published in the April issue) of the Leeds & Liverpool Canal being Britain’s ‘longest single canal’, ‘longest canal built as a single entity’ or some similar description. So what does that mean? Is it or isn’t it the longest of our canals? Well, yes and no…

There were longer mileages of waterway that were operated by a single company, and under a single name. For example the Birmingham Canal Navigations network extended to around 160 miles at its maximum extent.

The Grand Union Canal is even longer: the main line from the Thames at Brentford to Birmingham’s Salford Junction runs for 137 miles; then there’s the Leicester Line, the Erewash, the Regents and the various arms and branches. Altogether including the now abandoned branches it totalled around 275 miles. And the Shropshire Union system at its greatest extent (which included the Llangollen and Montgomery canals, now regarded as separate waterways) reached around 200 miles. But all of these were the result of takeovers and amalgamations of shorter individual canals which had been built by separate companies, none of which individually reached as much as 100 miles. For example the Grand Union Main Line is made up of what was originally the Grand Junction Canal, Warwick & Napton Canal, Warwick & Birmingham Canal and Birmingham & Warwick Junction Canal (also known as the Saltley Cut).

By contrast, the Leeds & Liverpool was conceived as a single entity, authorised under a single Act of Parliament in 1770 and finally completed, some 46 years later, by a single company. It cost not far short of £1 million – an immense amount in those days – and its construction must have taken up almost the entire working lifetime of many who worked on it. For example Joseph Priestley, taken on at the start as a book keeper while in his twenties, had risen to be overall Superintendent by the time it opened in 1816. He died, aged 74, the following year.

It was a huge undertaking, with its 127¼-mile main line (plus branches), and it deserves to be recognised as such.

As featured in the May 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the May 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here