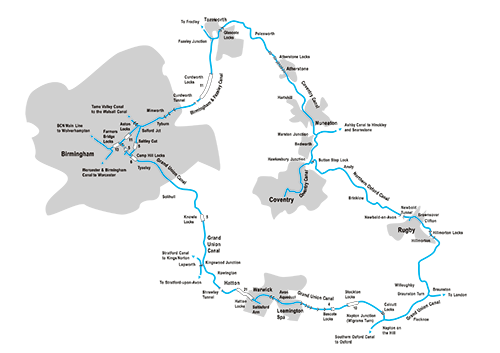

In the second half of our guide to this popular Midlands cruising circuit, we follow the Coventry and North Oxford canals south through Midlands countryside from Fazeley to Hawkesbury Junction and on to Braunston and Napton.

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

We ended the first part of this guide at Fazeley, one of a number of places whose importance on the canal network means that they’re rather more widely known to boaters than to the general populace.

We ended the first part of this guide at Fazeley, one of a number of places whose importance on the canal network means that they’re rather more widely known to boaters than to the general populace.

To the wider world it may just be a small town on the outskirts of the much larger Tamworth, but to the canal system it’s a significant junction. This is where the Birmingham & Fazeley Canal, part of the Birmingham Canal Navigations network and a busy route bringing cargoes of coal down from the Black Country collieries, met the Coventry Canal which provided the next link in a chain of waterways leading down to London and the South. Today, it’s a handy stopping place at the meeting point of three cruising circuits – the Leicester Ring, the Black Country Ring, and the one we’re following: the Warwickshire Ring.

Having said that, it’s not actually in Warwickshire: for just a few miles the Ring leaves its eponymous county and runs through Staffordshire. As you turn to the right at the junction, following the route that the coal heading south would have taken, look out for the fine junction cottage overlooking the junction (it has a number plate on it, like all BCN cottages) – but do also pay attention to your tiller, especially if you’re in a full-length boat, as it’s a sharp turn from one tightish bridge-hole around the junction into another one.

The Coventry Canal, together with the Oxford Canal, formed one of the arms of famous canal engineer James Brindley’s ‘Grand Cross’ of waterways linking four of the country’s great rivers – the Thames, the Severn, the Mersey and the Trent. It’s tempting to say that this is the northernmost point on the ring, and that we’re heading back down south now, but a glance at the map shows that’s not quite true. Such are the meanderings of this early canal, built in the days when avoiding heavy earthworks was more important than making a direct route, that it actually heads northeastwards for a few miles.

Part of the reason for these meanderings was to facilitate a crossing of the River Tame. When we last crossed it at Aston Junction (see Part One in the August issue) it wasn’t much more than a large stream (Tame by nature as well as by name?) but anow it’s a sizeable river which the canal crosses on a sturdy three-arch masonry aqueduct (guarded by a Second World War pillbox at one end) not long after leaving Fazeley.

On the Coventry Canal south of Tamworth

It’s not far to Glascote, where we meet the first two locks on the Coventry Canal. They’re narrow beam (as are all the locks between here and Braunston), and they have a bit of a reputation for being slow to fill. They were equipped with water-saving side-ponds, which can still be seen albeit out of use – operating them must have really slowed things down.

But unlike the first part of our journey, the locks on the east side of the Ring are far fewer (just 17 in around 50 miles, compared to the 62 in a similar distance in Part One) and are grouped together in flights. So having climbed these two locks, boat crews can put the windlasses away for a few miles as the canal winds its way out of the Tamworth built-up area and into what’s now East Midlands countryside but was once a coal mining area.

It’s also noticeable that after something of a dearth of boatyard services on the journey through Birmingham, there are several along here, including sites at Fazeley, Glascote and Alvecote – the latter being something of a Mecca for historic working boats, with some interesting craft usually to be spotted.

Traces of the former coalmining remain in the form of lakes and woodland formed from reclaimed industrial land including the Pooley Country Park on the former Pooley Hall Colliery site. Passing through Polesworth village, the canal follows the little River Anker on its left-hand side with gently rising hillsides on the right. (In fact, for most of the length of the Coventry Canal, it follows the contours with the land rising to the right and falling to the left). The West Coast Main Line railway provides a rather noisier companion as the canal approaches Atherstone.

Attractive countryside near Polesworth

After a seven-mile break, the climbing continues with the eleven locks of the Atherstone Flight. They begin with widely space locks in open countryside, and end with a steeper ascent into the town centre. They too can be rather slow to fill – so allow plenty of time.

The attractive old buildings at Hartshill Maintenance Yard

Atherstone is a market town once famous for making hats – the industry once employed some 3000 people, but the last factory shut in 1999; today it’s a useful stopping point with shops and pubs.

Leaving the town behind, the canal once again follows the characteristic winding route of an early contour canal, with the land falling away to the River Anker on the east side, and often wooded hillsides to the west. Look out for Hartshill canal maintenance yard, with its splendid main building crowned by a clock tower, and fine old hand crane.

Hartshill Castle and Country Park

Hartshill Castle and Country Park

If you fancy a walk from the Coventry Canal, head southwest from Bridge 32 (near CRT’s Hartshill Maintenance Yard) for three quarters of a mile and you will reach Hartshill Hayes Country Park, 137 acres of ancient woodland traversed by paths. See also the surviving ruins of the former Hartshill Castle nearby, as well as earthworks surviving from Oldbury Camp iron age hill fort, and views over the surrounding countryside.

We’ve moved from a former coalfield to an area once heavily quarried for stone, leaving some enormous holes and sizeable spoil tips; once again, some of the remains of this industry have been transformed into nature reserves.

This area leads to the edge of Nuneaton, the largest town on our route – or perhaps not quite on it. The canal actually skirts around the edge of the town, running past housing estates and playing fields some distance from the town centre. If you want to visit the shops, Bridge 20 is a handy place to moor and less than a mile from the centre.

The long lock-free level continues south of the town, as the canal passes through another former colliery area – this was where some of the last regular narrowboat cargoes were loaded, with the canal busy with coal boats well into the 1960s. You can still make out some of the old colliery arms where they loaded (see our Cruise Guide Extra on the following pages) on the approach to Marston Junction.

Passing through Bedworth

The Ashby Canal turns off left through an old stop-lock (a former shallow water-regulating lock, now minus its gates so you can cruise straight through) at Marston: if you’ve got two or three days to spare and fancy an even lazier cruise than you’re already having, this canal provides the ultimate lock-free getaway with 22 miles of rural cruising without a single lock.

If not, carry on south past Bedworth (and another old colliery loading arm) to reach the next junction at Hawkesbury.

There’s another worthwhile (and also lock-free) diversion for those with plenty of time: you can continue straight on for the final five and a half-mile dead-end length of the Coventry Canal leading into the city centre basin within easy walking distance of the cathedral and other attractions. Alternatively, take it gently as you pass the old pumping engine house and footbridge on the approach to the junction, before turning very sharply to the left to make a 180-degree turn under the classic iron towpath bridge, past the Greyhound pub, and into the stop-lock forming the start of the Oxford Canal. It’s a thoroughly awkward turn in a full-length boat, and there might seem no obvious reason for it. But it’s all to do with 18th century inter-company canal politics, with both the Oxford and Coventry companies determined to get the best out of any toll agreements concerning through traffic between the canals – to the point where they built their two canals parallel and just a few yards apart for a mile towards Coventry before they finally met. It must have been infuriating for boaters who had to go all the way along one and then back along the other, until they finally saw sense and cut a new connection between them here at Hawkesbury.

Unusually, unlike most stop-locks (like the one at Marston Junction) which have long since lost their function to protect companies’ water supplies from being lost to their rivals and are generally just gateless old reminders of the past, Hawkesbury is one of four on the network which are still working locks. It raises boats all of six inches or so. But make the most of it, because you won’t see a ‘real’ lock for another 15 miles or so…

(Incidentally, in case you’re were wondering, the other three working stop-locks are Hall Green at the south end of the Macclesfield Canal; Autherley on the Shropshire Union; and Dutton at the north west end of the Trent & Mersey).

A typical straight wide length dating from the 1830s improvements to the North Oxford Canal

The northern section of the Oxford Canal has a split personality – and that’s a result of its late 18th century and early 19th century history. As built, it wasn’t just a contour canal, it was one which took the concept to extremes.

If you’re familiar with the southern length of the same canal you’ll know the summit section from Napton to Claydon, which winds around the hills so much that a four-mile distance ‘as the crow flies’ takes eleven miles by water. But at least its builders had the excuse that it’s running through some hilly terrain where there was something to be gained from avoiding heavy earthworks. The northern length ran through gentler countryside, but if anything, its engineers laid it out on an even more sinuous course, wandering miles out of its way to avoid even the smallest embankment or cutting. It was said that you could boat all day within the sound of Brinklow Church’s bells.

Quite why they did this is not entirely clear – it’s often blamed on James Brindley, but many of his even earlier canals were less winding. By the time this section was built he had died, and the job had passed to one of his informal ‘school’ of assistants, Samuel Simcock, who tends to get the blame for taking a sensible idea to extremes. Some wag suggested that he wanted to sign his initials across the country in water!

Whatever the reason, it delayed traffic to the point where there were proposals in the late 1820s for a shorter rival canal from the Stratford Canal to Braunston, which would bypass the Oxford’s indirect route. This stung the Oxford company into action. They came up with their own plan for improving the route, by a whole series of short-cuts which bypassed the more meandering parts of the original line. Altogether they lopped some 14 miles off its total length in the 1830s.

So, today’s canal alternates between surviving parts of the original winding route, and straight wide cuttings and embankments dating from the improvements. Just within the first few miles as the canal passes Wyken and Ansty you can see good examples of both. And look out for old arms going off, with characteristic cast iron bridges carrying the towpath over them: these were short lengths of the original line which were retained as they served local wharves. Many have found new uses – the one at Wyken leads to a mooring basin.

A long, straightish cutting followed by an embankment carries the canal alongside the mainline railway – this was clearly part of the 1830s improvement – and leads to Stretton Wharf where another surviving fragment of the original canal leads to a boatyard.

The canal retains its rural appearance as it skirts Rugby

Brinklow Arches (note the plural) is a one-arch aqueduct, its name recalling the original narrow multi-arch structure also rebuilt in the 1830s. Brinklow village is now some way from the canal (it was on the original route), but has useful pubs and shops and is within walking distance of Bridge 34.

A straight cutting leads to Newbold Tunnel, a short but impressive structure dating from the 1830s improvements, which is not only wide enough for boats to pass inside, but also has a towpath on each side. If you moor up at the south end (and there’s a pub there, so you might well!) you can take a short walk to the church, follow a footpath leading out of the churchyard, and find a bricked-up portal of the original tunnel.

The expansion of Rugby is approaching Newbold these days, and there isn’t much open countryside before the canal enters the urban area, running along the northern edge of the town. More features from the canal’s 1830s improvements include aqueducts crossing the infant River Avon and a former main road. The closest approach to the town is at Bridge 59.

Rugby School and Webb Ellis Museum

Rugby School and Webb Ellis Museum

The school made famous by Tom Brown’s Schooldays and the legendary invention of rugby football is open for drop-in public tours of the school and its museum on Saturdays (turn up at the School Shop at 2pm – or book places in advance by phone or email to avoid possible disappointment). And while you’re there, visit the nearby Webb Ellis Rugby Football Museum, a small museum packed with rugby memorabilia

As Rugby is left behind, the canal finally approaches the first lock since Hawkesbury, and (given the 6in rise of Hawkesbury Stop Lock) arguably the first ‘proper’ lock in 25 miles from Atherstone. The three Hillmorton Locks were so busy that they were duplicated as pairs of side-by-side locks – and it’s just as well that they were, as they regularly top the list in the Canal & River Trusts Annual Lockage Report for the busiest on the entire network. A team of volunteer lock keepers are often on duty to help keep things moving.

A towpath bridge indicates where a section of the canal’s original route was bypassed by the 1830s improvements

The next few miles to Braunston run through quiet countryside, with hills on the left and views of the spire of Braunston Church ahead on its prominent hill-top site.

Braunston is where we once again briefly leave Warwickshire, this time to pass through a few miles of Northamptonshire. It’s also a classic canal village, a key point on the waterways network where the Oxford and Grand Union canals meet, a busy canal boating centre both today with many waterway’s businesses based there, and in the past when it was central to the working boat trade and the lives of its people.

Our journey actually doesn’t quite make it into Braunston – it’s another place that was on the Oxford Canal’s original route, but was bypassed by the straightenings. However, it would be a shame not to visit such an important canal centre, so carry on left past the junction known as ‘Braunston Turn’ – you can turn round at the entrance to the marina.

On the North Oxford Canal between Hillmorton and Braunston

Braunston Turn is a distinctive junction with a pair of cast iron towpath bridges, and leads onto a long straight length of canal dating from the 19th century improvement programme. It’s also seen a further upgrade in the 20th century: although it was built as part of the Oxford Canal, it also forms part of the Grand Union Canal’s route from London to Birmingham – and therefore it was included in the work to enlarge the northern part of that route to take wide-beam boats (See our Cruise Guide Extra in the August issue for the story of this work).

You’ll see signs of 1930s concrete piling and new bridges from that era, as you follow the gently meandering five miles to Napton, including a couple of main road bridges

which (although wide) are both on blind bends.

Finally, a 1930s concrete towpath bridge on the right shows where the northern Grand Union continues towards Birmingham – and where we started our journey last month. Take this turn to continue on the Warwickshire Ring; or carry on straight ahead for Banbury, Oxford and the Thames.

As featured in the September 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the September 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here