The recent completion of the new Schoolhouse Bridge marks the removal of the last road blockage which stood in the way of reopening the English length of the Montgomery Canal. But it’s more than that – it’s a key part of eliminating the gap between English and Welsh restored sections, as Martin Ludgate found out…

For a non-opening of a bridge over nothing, it wasn’t a bad turnout. Forgive my flippancy, but at first glance there might have been some raised eyebrows at the sizeable attendance at Schoolhouse Bridge on the Montgomery Canal, including representation at the top level by the Canal & River Trust as well as the various bodies more directly involved in this canal, and local officials from parish councillors up to the Lord Lieutenant of Shropshire. And all this was to mark the completion, christening and unveiling of a commemorative plaque on a new bridge which had already been opened to road traffic, but which won’t see its first boat until this section of the canal channel has been rebuilt.

For a non-opening of a bridge over nothing, it wasn’t a bad turnout. Forgive my flippancy, but at first glance there might have been some raised eyebrows at the sizeable attendance at Schoolhouse Bridge on the Montgomery Canal, including representation at the top level by the Canal & River Trust as well as the various bodies more directly involved in this canal, and local officials from parish councillors up to the Lord Lieutenant of Shropshire. And all this was to mark the completion, christening and unveiling of a commemorative plaque on a new bridge which had already been opened to road traffic, but which won’t see its first boat until this section of the canal channel has been rebuilt.

Not just any bridge

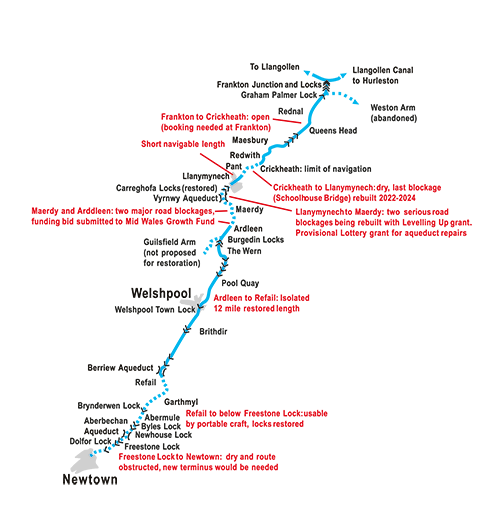

But this isn’t any bridge. It’s one whose location has great strategic significance, and whose construction comes at a critical stage in the long-term (over 50 years already) campaign to reopen the 30-plus miles of historic canal running through spectacular Border Country and Welsh scenery from Frankton Junction on the Llangollen Canal through to Welshpool and on towards Newtown. And in the absence of major funding grants for this type of work on this section of the canal, its construction has been made possible by an impressive fundraising effort by the Montgomery Waterway Restoration Trust and other bodies.

So where is it? It’s around eight miles along the canal from Frankton, down Frankton and Aston locks, through Maesbury, past the new (since 2023) limit of navigation at Crickheath Wharf and on for about another half mile along the dry channel beyond. In the other direction, it’s about two miles from where the canal crosses the Welsh border at Llanymynech. And that border crossing is the most significant thing about the bridge’s location…

After the canal was officially closed by the 1944 LMS Railway Act (having already been out of use since a breach went unrepaired in the 1930s), many road bridges over it were demolished to remove impediments to motor traffic, and replaced by small low level culverts maintaining any remaining flow of water. The need to reinstate these missing bridges has been one of the main obstacles to restoration, but they have gradually been dealt with as money has become available. Two on the English length – the old A5 crossing at Queen’s Head and the B4396 at Redwith – had already been reinstated, allowing the canal to reopen to Crickheath. That left Schoolhouse Bridge as the last remaining road blockage on the English length of the canal.

Reinstating the bridge would therefore be a highly symbolic step forward, clearing the way to re-establishing the navigable link between the two nations. But it would also be an important move from a practical point of view, as different areas qualifying for different funding sources have often meant that it has been more difficult to finance the restoration in England than in Wales. Get the canal open from Frankton to the border, and… well, I wouldn’t say “the rest is easy”, but it should make it a whole lot more possible.

The same scene before the new bridge was built

The new Schoolhouse Bridge

Getting it funded and built

With this in mind, MWRT set to work on getting the bridge designed and raising the cash to build it – about £1.1m, as it worked out. An important £70,000 came from the Inland Waterways Association’s Tony Harrison legacy, and there were contributions from local and national charity and community funds, from the Friends of the Montgomery Canal’s annual Triathlons, the local IWA branch and the Shropshire Union Canal Society, and many individual donations of up to £10,000 in one case – as well as a very generous anonymous donor who ‘matched’ many of the contributions.

SUCS and MWRT volunteers (whose ranks include such useful people as retired civil engineers and retired lawyer Michael Limbrey who chairs MWRT) contributed to the design and initial works (such as creating a temporary road diversion) as well as the legal paperwork (12 agreements totalling some 150 pages!) before handing over to contractors Beaver Bridges to build the brick-faced concrete arch structure, then finally IWA’s volunteer arm the Waterway Recovery Group spent a four-day Easter 2024 Canal Camp on finishing-off works.

The bridge was declared open at an event in February 2024 featuring a convoy of historic vehicles; it opened to normal road traffic a few days later; WRG achieved a rather different ‘first’ by driving a dumper truck under it at Easter! The June event saw Lord Lieutenant Anna Turner, official representative of the King in Shropshire, unveil the commemorative plaque, following which the bridge was christened with Monty’s Brewery’s Navigation Pale Ale (well, actually they couldn’t bring themselves to waste any beer, so they substituted water!)

But what about getting the canal there?

However, as I mentioned earlier, there weren’t any boats under the bridge, because the channel hasn’t been restored yet. But SUCS volunteers are hard at work on the section between the new bridge and the limit of navigation at Crickheath. There’s a lot more to this than a simple vegetation clearance and channel re-profiling: these lengths of the canal suffered from chronic leakage and water loss problems, have been dry since it closed, and need to be made watertight before they can be rewatered. In the old days this would have meant large amounts of puddled clay; today’s methods adopted by SUCS include modern synthetic lining sheets held in place and protected by a layer of concrete blocks.

These methods were developed on the Redwith to Crickheath section opened last year, and are now being used south of Crickheath. However, not all of this section will be lined: the canal has been divided into sections by creating bunds (temporary clay dams) so that ‘stilling tests’ could establish which parts would hold water, and which parts wouldn’t and needed lining. In addition, work has included restoring a historic wharf wall where a horse-tramway once brought limestone down from quarries to be loaded into boats.

Even using volunteer labour, this all costs a considerable amount of money for materials, machinery and other costs – but a £177,000 Rural Prosperity Fund grant has helped, and a £250,000 appeal launched by MWRT is currently just over halfway to raising the remainder.

How long it will take depends on how much lining is needed; there’s also a farm access crossing that needs replacing with a new bridge (possibly a lift-bridge – these were a feature of the canal and there are already two on the navigable length) before boats can reach Schoolhouse Bridge. Michael Limbrey tells me it’s hard to give a more precise date than “the next few years”.

And so to Wales…

The same applies to the next length beyond Schoolhouse Bridge, where the dry section continues for another mile and a half through Waen Wen and Pant, before water reappears at the start of a mile-long navigable length (with trip-boat operation) through Llanymynech. Although as we said earlier there are no more road crossings to be dealt with, and a former railway embankment blocking the canal was removed by WRG volunteers some years ago, it won’t be entirely straightforward. The main issue is a sewer laid in the canal bed for a quarter mile – as it happens, the sewer needs attention anyway so discussions are under way with Severn Trent Water to try to get this work prioritised and combine it with moving the sewer out of the canal.

It’s also not yet clear how much of the channel needs re-lining: all that’s known for sure is that by the time it gets to Llanymynech the original canal bed is capable of holding water.

But the result will be a further reopening of two and a half miles of canal, including a great deal of heritage interest with old limekilns and former tramways, some very attractive scenery – and the all-important Welsh border.

This is marked by bilingual ‘Welcome to Wales’ and ‘Welcome to England’ signs on the two sides of a bridge right in the middle of Llanymynech. That’s right, the village is split between countries, which has led to some complications at times, especially before 1968 when the pubs on the Welsh side weren’t allowed to open on Sundays. One pub actually straddled the border, and so one of its bars was strictly Mondays to Saturdays only!

The importance of reaching Wales

But I digress. It’s importance to the canal restoration is that on the next section, Powys Council has succeeded in securing almost £15m from the Levelling Up Fund – which is all to be spent on the Welsh section. Although inflation has had an impact since the grant was announced, it will still pay to deal with two road blockages south of Llanymynech – both of them awkwardly sited. The first is at Walls Bridge, where the old hump-back bridge still stands, but its road approaches involved a sharp bend and a steep hill leading down to a T-junction – so the road was diverted around it and crosses the canal at just above water level. A longer road diversion is planned along with a short canal diversion, so that the road can cross the canal via a new bridge which will be high enough for navigable headroom, but still approach the main road on a gentler gradient, and provide acceptable traffic sight lines.

Williams Bridge, controversially flattened in the 1970s, is to be replaced by a new lift-bridge

The second crossing is the site of the old Williams Bridge, notorious among canal restorers for being the last original bridge to be demolished, at a time in the late 1970s when canal restoration was already under way. I recall the then highway authorities justifying their actions on the grounds that the bridge was in poor condition, inadequate for the fairly busy road (it was a narrow hump-backed bridge with single-lane traffic controlled by traffic lights), and could be replaced by a new structure at such time as the canal were to be restored. They might have been right, but at the time it felt like a kick in the teeth for the restoration.

A new lifting bridge will take its place, power operated and with barriers and warning lights: Michael Limbrey remarks drily that almost half a century after the traffic light control was seen as a reason for removing the old bridge, we’re about to introduce traffic light control on the new one…

Between these two bridges are Carreghofa Locks, fully restored many years ago by SUCS volunteers and patiently awaiting the boats. And just beyond Williams Bridge is the Vyrnwy Aqueduct, an important historic structure in need of restoration – but with a bid by CRT to the National Lottery Heritage Fund for £2.1m of the £4m cost already having been given provisional approval.

With the Levelling Up Fund money also paying for dredging, bank protection work, and one of three off-line wetland nature reserves required under the canal’s Conservation Management Plan (an agreement thrashed-out some years ago between all interested parties from navigation and nature conservation interests) as a condition for reopening to boats, boats from the national network could get through to Maerdy in the not too distant future.

Two tricky problems

That’s where they would reach the first of two major problems: the A483 main road crosses the canal twice in the space of a mile, at Maerdy and at Arddleen – in both cases at not much above water level. But the circumstances differ significantly…

At Maerdy, the canal has been culverted and a new bridge will be needed – and it’s likely that to provide acceptable sight lines for traffic on a busy main road, this will mean diverting the canal to cross the road where it can be done with the minimum raising of the road level. This will be expensive, but conventional enough.

Arddleen Bridge: this is actually a full-size bridge with towpath, but designed and built on the basis that the canal would be lowered by 8ft to get under it

At Arddleen, by contrast, a bridge already exists, but at the wrong height. The road crossing here was built some 40 years ago as part of a bypass around Arddleen village – and by that time the canal was already under restoration, so the road builders catered for it in their plans. But rather than going to the expense of raising the road to provide full navigable headroom for a canal restored at the original level, they built the bridge to cater for a restored canal running in a cutting approximately 8ft lower than the historic level. The intention was that the canal all the way from here to the next lock at Burgeddin would be lowered by 8ft, the lock would be abolished, and a new lock north of Arddleen would take the canal back to the original level.

This would have meant a huge amount of earthworks to lower over a mile of canal, as well as demolishing an attractive and historic lock – but was accepted as a price for getting any kind of provision at all for crossing the road. Today’s plans instead foreseee some kind of ‘drop lock’ to lower boats on one side of the road and raise them again on the other side (like the one in Dalmuir, built during the Forth & Clyde Canal restoration to deal with a similar problem). Actually, it’s more likely (to avoid the requirement for permanent staffing on safety grounds – you don’t want to risk somebody making a mistake and getting their boat stuck under the road amid rising water!) that it would be a ‘drop pound’ – a short lower length of canal with a conventional lock at each end of it. A high-capacity overflow would get rid of any surplus water to avoid any possibility of boats getting stuck under the bridge; a back-pump would compensate for water usage by the locks; a bypass pipe would allow water to pass along the canal. All this may sound expensive, and indeed it won’t come cheap. But CRT is looking to the Mid Wales Growth Deal’s £110m of public money for a ten-year programme funding projects across the region. With its ability to provide benefits all along the length of the route, the canal is thought to be well-placed for this. More money would be needed from other sources (and clearly CRT’s own resources have to go on the core maintenance of the existing network – especially in its current straitened circumstances). It might be possible to go for a ‘phased’ approach to split the work – but it doesn’t really make sense to deal with one road crossing and not the other. It’s a conundrum, but CRT is talking to both the Government and the Welsh Assembly, and has some hope of success.

A 12-mile length through Welshpool is already restored, and used by these disabled accessible trip boats

Linking up to Welshpool

And if it does come off, that’s what would bring the big benefits. South of Arddleen it would connect up with the start of a fully restored length (albeit one needing a fair bit of TLC in places) that extends for 12 miles, all the way through Welshpool and a fair amount of the way to the original terminus at Newtown. It genuinely might not be many years before we have a 27 mile continuously navigable waterway from Frankton to Berriew.

Beyond Berriew?

And then what? Well, three locks beyond Berriew have already been restored, two of them by SUCS volunteers. There are more road crossings to be dealt with, but no insuperable obstacles to reopening for a further six miles to where the Penarth feeder supplies water from the River Severn.

Beyond there, it gets tricky for the final couple of miles into Newtown. This section lacked a water supply so it had to be fed by pumps, has now run dry, and has been sold off; another sewer has been laid in the bed for part of the way; the original terminus basin has been filled in and built on; flood relief works make finding an alternative route alongside the river tricky.

But MWRT has an aspiration to get to Newtown somehow. The Council has just acquired the original pumping station building and is reinstating a length of missing towpath; MWRT took the opportunity to acquire the very derelict Dolfor Lock and several hundred yards of canal to protect them for the future; and there is support in the town for finding a way to bring back the canal. It might need a certain amount of innovation…

With his tongue in cheek and a nod to the well-known Scottish boat lift, Michael Limbrey says “It could be the Falkirk of Mid-Wales!”

As featured in the September 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the September 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here