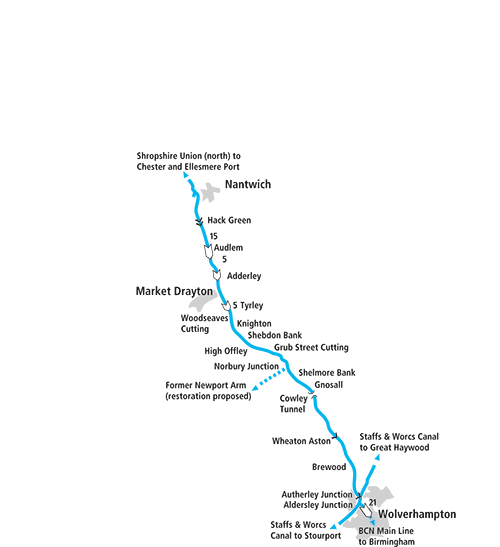

In the first part of our two-part guide to the ‘Shroppie’, we follow the southern length from Autherley Junction to Nantwich as its bold engineering cuts across the landscape with high embankments, deep gloomy cuttings, and attractive flights of locks.

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

Many years ago, when I was young, and when young people wore badges, I somehow acquired one (I forget where) which simply said “Where the hell is Autherley Junction?” I’ve no idea where it ended up, and I don’t think I ever saw anyone else wearing one – were they, perhaps, a series? Anyway, I felt at the time that it rather summed up the idea of the “canal place” – somewhere of vital importance to the waterways network, but otherwise so small that hardly anyone outside the canal world has even heard of it. See also: Braunston, Marsworth, Fradley, Stoke Bruerne and many more…

Many years ago, when I was young, and when young people wore badges, I somehow acquired one (I forget where) which simply said “Where the hell is Autherley Junction?” I’ve no idea where it ended up, and I don’t think I ever saw anyone else wearing one – were they, perhaps, a series? Anyway, I felt at the time that it rather summed up the idea of the “canal place” – somewhere of vital importance to the waterways network, but otherwise so small that hardly anyone outside the canal world has even heard of it. See also: Braunston, Marsworth, Fradley, Stoke Bruerne and many more…

But back to Autherley, and where the hell it actually is. Well, it’s the important junction where the south end of the Shropshire Union Canal meets the approximate mid-point of the Staffordshire & Worcestershire Canal. And in the real world, that would appear to narrow it down to one of three counties. And of those three it was actually in Staffordshire (until the new county of West Midlands was created in the 1970s), on the outskirts of Wolverhampton. It’s about half a mile northeast of the confusingly similarly-named Aldersley Junction (apparently, they originated as two different variants of the same name) where the main line of the Birmingham Canal Navigations branches off the Staffs & Worcs at the start of its journey to Birmingham. So it was, and still is, an important point on the Midlands waterways. And it’s where we’ll start our cruise northwards along the ‘Shroppie’, as the Shropshire Union became colloquially known.

The actual junction features a bridge to carry the Staffs & Worcs towpath over the Shropshire Union, and if you’re coming from the north east direction, from the direction of Great Haywood and the Trent & Mersey Canal, it’s quite a tight turn into the narrow bridge entrance, which leads straight into Autherley Stop Lock. This is one of those very shallow locks which were often built at junctions of two canals, to restrict the flow of water between waterways, protecting the jealously-guarded water supplies of the individual canal companies, who were often at loggerheads with each other over such things. Actually, in this case the inter-company rivalry led to a proposal by the Shropshire Union and BCN companies to bypass the Staff & Worcs altogether, by building a short new link canal that would have crossed the S&W on an aqueduct!

With such inter-canal disputes having been consigned to history with almost all canals coming under common ownership. Most of these stop-locks have lost their purpose and their gates, and all that remains is a narrowing of the channel – but Autherley is one of four on the network that survive as working locks (the others being Dutton, Hall Green and Hawkesbury). So, enjoy the gentle exercise of lowering your boat by all of six inches, because you won’t be using your windlass much for a while. In fact, enjoy the junction too, because you won’t be doing a huge amount of steering either…

Aqueduct by Thomas Telford crossing the A5 main road

Yes, this part of the Shropshire Union is generally pretty straight, and level. And boring? No, far from it. It’s straight and level not because the land it passes through is flat, but because its engineer Thomas Telford was working on it at the end of the main canal-building era, with the benefit of over half a century of engineering development since the Staffs & Worcs was built, and with a determination to build a route that was direct enough to compete with the railways whose first main lines were already under construction. And that meant high embankments and deep cuttings as the canal sliced its way through some fairly hilly countryside on its way north. The greatest of these feats of civil engineering are still some way ahead, but even in the first few miles you’ll pass enough cuttings and embankments to make it clear that this is a very different canal to the Staffs & Worcs.

Crossing one of the canal’s many embankments

Note that I said “This part of the Shropshire Union” above. The Shropshire Union, as its name might suggest, was actually an amalgamation in the 1840s of several existing canals (most of which reached a long way beyond Shropshire). These included the whole of what we now call the Llangollen Canal (but was originally called the Ellesmere Canal) and the Montgomery Canal, while the main north-south route that we call the Shropshire Union was made up of another part of the Ellesmere Canal at the north end, then the Chester Canal, and finally the part we’re travelling on – which Thomas Telford would have called the Birmingham & Liverpool Junction Canal. It doesn’t go to either of these cities – but its name reflects its intended function as part of a direct long-distance through route. It also differs from the other parts of the main line in that it was built narrow-beam: by the 1830s any hopes of creating a wide-beam national network had faded, and engineers accepted that the 70ft by 7ft narrow boat would be the standard for the midland network.

Loynton Moss

Loynton Moss

This nature reserve can easily be reached from the canal at Bridge 39, Grub Street Cutting. A relic from a former lake left by the retreating ice age 10,000 years ago, it is a rich, diverse wetland bog teeming with numerous insect species which attract many birds including reed bunting, willow warbler, reed warbler and buzzard. Plants include tall reed species, there are numerous species of butterfly, and in spring there are bluebell and stitchwort flowers. Be warned: in summer there are mosquitos!

Other features to note in the first section are the attractive brick-built hump-backed bridges – and a splendidly ornate one carrying a private drive to a manor house – as well as a fine cast iron aqueduct carrying the canal over the A5 main road.

Despite its aim to be a direct route for long-distance traffic, the canal does pass through some attractive and useful villages to moor up in – and the first of these is Brewood (pronounced ‘Brood’) with the first waterside pub on the canal. Wheaton Aston too features a waterside pub – as well as a chance to flex your windlass muscles for the first time in seven miles since Autherley as the long descent to the Cheshire Plain begins. But the lock, unlike most that we’ll meet on this section, stands alone rather than forming part of a flight – and it’s an even longer distance till the descent continues. Note the grey-and-white painted gates (this was traditional on the Shropshire Union, rather than the black-and-white found elsewhere) – but perhaps more importantly, note the outfall from the ‘bywash’ (overflow channel) – these can be quite fierce and push you off course if you aren’t expecting them.

Dramatic rocky entrance to the largely unlined Cowley Tunnel

Embankments and cuttings keep up the interest, while stone has replaced brick as the building material of choice for the bridges (and there are some fine examples of the stonemason’s art) as the canal passes through quiet countryside to reach a deep rocky cutting at Cowley. This leads to the 81-yard Cowley Tunnel, impressively cut to the full width of the canal rather than narrowing-down to a single boat width, and running largely unlined through the sandstone rock. It was planned to be much longer which would have been even more impressive, but unstable rock led to part being completed as a cutting. It leads straight into the attractive canalside village of Gnosall, a useful place to moor for shops and yet another waterside pub.

Speaking of mooring, I should mention the ‘Shroppie Shelf’ – a below-water ledge dating from bank rebuilding which is a feature of the canal from here northwards, and can make it tricky to get close to the edge, or result in your hull scraping if you do. Local boaters tend to acquire suitable fenders (in some cases small wheelbarrow tyres) to protect against it.

The trees hide the fact that this boat is crossing the massive and difficult to construct Shelmore Embankment

The canal engineering has been impressive so far, but now it ‘changes up a gear’. And the first sign of this, soon after Gnosall is left behind, is a short narrowing of the channel with a single lock gate. Another leftover from canal companies guarding their water supplies? No, in this case it’s to make it easy to close off a section of canal in case of a leak or a breach, to limit the damage and water loss. And the reason it’s here is because the canal is about to launch out onto Shelmore Bank, one of the biggest embankments on the route at 60ft high. It was a real headache for the canal’s builders, with repeated collapses and slips delaying its completion – and Thomas Telford didn’t quite live to see it finished. And it wouldn’t have needed to be anything like that size if the canal hadn’t been required to divert slightly to avoid the local squire’s pheasant hunting land. The stop gates are still maintained, and during the Second World War they were closed every night in case the embankment was bombed. Unfortunately, the growth of trees and vegetation mean that it’s difficult to appreciate its size from the canal – but a couple of aqueducts over small roads give more of an idea.

Not far beyond the aqueduct the canal reaches Norbury Junction – today a handy canal centre with moorings, boatyard, drydock and pub, but formerly the starting point for a connection to Shrewsbury (now under restoration by the Shrewsbury & Newport Canals Trust) and the once extensive Shropshire tub-boat canal network.

Norbury Junction, where the Newport Arm used to branch off under the bridge on the left

We’ve seen the first seriously big embankment, and now we come to the first of the really deep cuttings, Grub Street. Its curving route (almost the first even very moderately sharp bend since Autherley Junction) is notable for High Bridge, whose high arch is cross-braced by a masonry support on which – rather incongruously – is mounted an old-fashioned telegraph pole, a relic from when the canal’s straight course made it (like many roads and railways) a good route to run telephone wires alongside.

The wharf at Knighton which once despatched boatloads of chocolate ‘crumb’ bound for Cadburys at Bourneville

Next comes the second of the major embankments, Shebdon Bank, which leads to Knighton Wharf. Knighton is another of those small and not very widely known villages with a greater importance in canal circles, as it was the site of the factory which was the origin of much of the traffic in chocolate ‘crumb’, carried by boats to Cadbury’s famous works in Bourneville, Birmingham, which turned it into the finished products.

And another four miles on, just past Cheswardine, comes the second and deeper of the two big cuttings at Woodseaves. Unlike Grub Street this one is mostly straight, and if you’re really lucky with your timings, you might get there in the late morning when the sun shines straight along it. It too is spanned by a bridge called High Bridge: this one doesn’t feature a telegraph pole, but its 70ft height is really impressive. The cutting sides are wooded, and the canal has a feeling of being cut off from one’s surroundings – all the more so at the moment, as the towpath has been closed and become overgrown since a landslip early this year, so walkers face a lengthy detour between bridges 56 and 59.

Not far beyond the end of the cutting, the long lock-free level finally comes to an end after 17 miles – and this time the descent is more rapid. The attractively situated and evenly-spaced, and equal depth (everything planned by the canal builders for efficient operation) Tyrley Locks lower the canal into another gloomy cutting, before it arrives at Market Drayton, the first town on the route. Its useful shops are around three quarters of a mile away to the west.

Dorfold Hall

Dorfold Hall

Dorfold Hall near Nantwich is a Grade I listed Jacobean mansion England, considered by art historian Nikolaus Pevsner to be one of the two finest Jacobean houses in the county. On Tuesdays and Bank Holiday Mondays from April to October the gardens are open to the public from 1pm to 5pm and there are guided tours of the hall at 1.30pm, 2.30pm and 3.30pm – book your tour online

Quieter countryside beyond Market Drayton leads to the next set of locks, the five at Adderley, and then there’s no real let-up before the long flight of 15 leading down through Audlem. Again, they’re mainly evenly spaced and close together (sufficiently so that there’s a YouTube video of a pair of working boats ‘longlining’ up the flight – towing on a very long rope, with the motor boat in one lock while the unpowered butty boat is in the previous lock), and there’s a good view down the locks into the village.

Market Drayton, the only town on the canal between Autherley and Nantwich

The bottom of the flight features not one pub but two (one of them featuring part of a boat hull as the bar – see our pubs list), as well as Audlem Mill, home to the well-known Canal Book Shop. The shops are easily reached from the bridge below the 12th lock.

The next few miles run through the flatter countryside with herds of black and white dairy cattle that are characteristic of the Cheshire Plain. Two last locks at Hack Green are accompanied by signs pointing (slightly startlingly) to the “Secret Nuclear Bunker”. Skirting the edge of Nantwich, an uncharacteristically bendy length of canal runs along an embankment and spans a main road on a cast iron aqueduct of very similar style to the one over the A5. And then, after passing under a narrow stone-built bridge, the canal meets what was once a different waterway. Here the Birmingham & Liverpool Junction Canal of the 1830s came to an end, and the next length of today’s Shropshire Union Main Line is formed by the former Chester Canal, dating from the 1770s.

Hack Green Secret Nuclear Bunker

Hack Green Secret Nuclear Bunker

A relic from the Cold War, the Bunker was one of a network of 17 sites throughout the UK designed to enable the government to continue in the event of nuclear war. Abandoned around 1992, it opened to the public in 1998 as a themed museum with Cold War memorabilia, decommissioned nuclear weapons, and a simulator designed to recreate conditions during a nuclear attack

It’s a pleasant spot, handy for mooring for the town, and with a boatyard based in the stub end basin that’s the original Chester Canal terminus. So we’ll stop here for now, and continue along the older canal in Part Two next month.

As featured in the October 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the October 2024 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here