A striking new bridge at Staveley is a step forward in the Chesterfield Canal’s restoration – but it’s also the key to unlocking further restoration work in the coming years, as Martin Ludgate finds out.

As reported in the news pages of the December issue of Canal Boat, on an unrestored length towards the west end of the Chesterfield Canal, a striking new bridge now spans the future restored route of the waterway. Some 38 metres long and weighing more than 40 tonnes, it carries the Trans Pennine Trail – a walking, cycling and horse-riding route – across the cutting through which the canal will one day run.

As reported in the news pages of the December issue of Canal Boat, on an unrestored length towards the west end of the Chesterfield Canal, a striking new bridge now spans the future restored route of the waterway. Some 38 metres long and weighing more than 40 tonnes, it carries the Trans Pennine Trail – a walking, cycling and horse-riding route – across the cutting through which the canal will one day run.

It was an impressive sight, watching the giant crane swinging the long slender steel structure into place – and by the time you read this, the finishing works should have been completed and the first walkers, riders and cyclists should soon be crossing. But as is often the case with projects like this, there’s much more to it than just the reinstatement of one missing bridge (even a spectacular one like this) – it’s the subsequent progress that will be enabled by the construction of the bridge.

The site of Bellhouse Lane Bridge, to be built during 2025-6

As Chesterfield Canal Trust’s full-time project manager George Rogers describes it, the installation of the new bridge isn’t just a necessary step in the long-term restoration of the canal; it’s also an ‘enabling work’ for what comes next.

A large part of that “what comes next” is the rest of the £5m package of works besides the Trans Pennine Trail (TPT) bridge which are also being funded from part of the £20m pot for Staveley under the Government’s Towns Fund. And the importance of opening the TPT bridge first is that it takes all the Trail users completely out of the way of the major construction site for the rest of the project, enabling the existing route (which crossed the canal on the level) to be closed, and the construction machinery to have free access. So what work is there still to do?

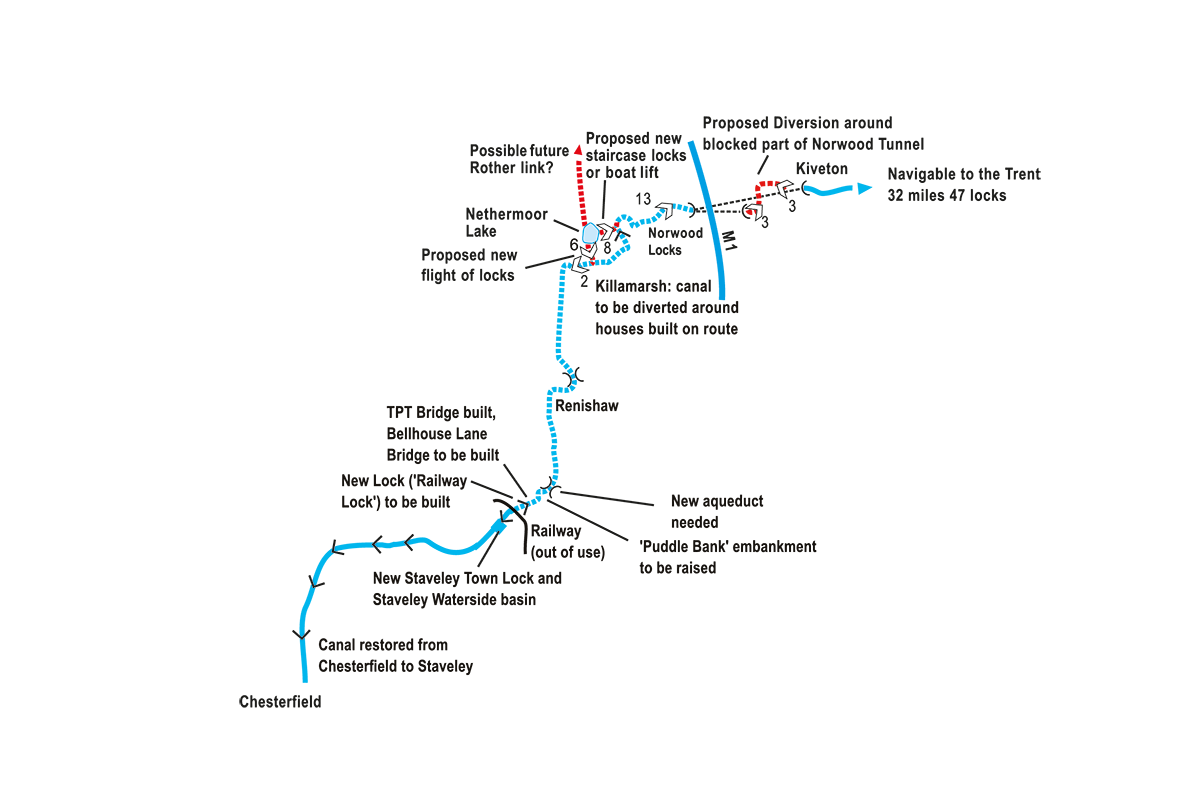

First, to get a better understanding of the project, we’ll briefly go back into the recent history of the restoration at this end of the Chesterfield Canal. With the canal’s westernmost five miles and five locks from Chesterfield down to Hollingwood having been completed, the next stage was to extend it to Staveley, where a large new basin was built to create a focus for the canal in the town. Staveley Town Basin, now known as Staveley Waterside, was opened in 2012.

Looking along the route of the canal at Staveley with the old railway bridge abutments in the foreground, the site for the new Railway Lock beyond (where the left-hand white van is), and the new bridge just visible beyond

Continuing north eastwards from the basin towards Renishaw and Killamarsh, the canal came up against some problems. The channel had been infilled in places; it had suffered from mining subsidence; and it ran through an area criss-crossed by former railway lines: one of these is now the TPT route, but another one still had rusty rails on it, and was officially ‘mothballed’ for possible future freight use. The bridge abutments where it had crossed the canal were still in situ, but the deck had been removed and the gap infilled, and subsidence meant that the rails crossed at such a height that there would been insufficient headroom for a new bridge to span the canal if restored on its original level.

So, a plan was devised to build a new lock (christened Staveley Town Lock) immediately northeast of the new basin, to lower the canal by 1.7 metres to enable it to pass under the railway track at a suitable height for reinstatement of a railway bridge with navigable headroom. And then, beyond the railway crossing, a second new lock would need to be built, to enable the canal to climb back to its original level. It wasn’t an ideal situation as regards water supply, but it was workable.

Staveley Waterside and the new Staveley Town Lock, largely built by volunteers

However, the headache for canal restorers resulting from the possibility of the return of freight trains was nothing compared to the grief that they suffered as a result of a rather more major railway proposal. In 2012, the route of the HS2 high speed line’s north eastern branch was announced. It not only came straight through Staveley, further complicating restoration of this length, but it followed the canal’s route northwards through Renishaw to Killamarsh, making it impossible to plan for restoration (a multi-million pound bid to the Heritage Lottery Fund for canal restoration funding which was felt to have a good chance of success couldn’t be submitted because of the uncertainty around HS2) and threatening to obliterate restoration work already carried out.

CCT’s volunteers carried on regardless with the new lock (for some time their site compound boasted a defiant “Up yours HS2, it’s business as usual!” sign); it was duly completed, and a sizeable section of the new lower-level canal channel beyond was built, passing under new road bridges built as part of the town’s new bypass, running alongside a large new overflow weir structure, and reaching to the site of the railway crossing.

In the meantime, the plans for HS2’s northeastern branch were changed, with the new line rerouted away from the canal – but a planned HS2 maintenance depot access siding would still need to cross the canal’s route on approximately the same site as the mothballed freight line (although HS2 would never actually confirm what height it would run at, making planning of new locks and bridges difficult – at one point it looked like a second new lock might be needed to lower the canal even further to get under it). Finally, in 2022 this branch of HS2 was shelved in its entirety. And in the meantime, any ideas of the mothballed freight line being needed again faded away.

So having spent upwards of a decade planning to get the canal around an awkward railway crossing, the restorers found themselves with much of the work at Staveley complete, but with no railway to cross! “So would the sensible way forward be to abandon the two new locks and reinstate the canal on the original level?” I ask George. No, he replies; not only was this branch of HS2 still officially ‘shelved’ indefinitely rather than completely abandoned (albeit with little chance of resurrection), but the work already done on Staveley Town Lock and bridge and the channel beyond, most of which would need to be demolished and replaced or heavily modified, meant that it would be much easier and cheaper to continue as planned. Meanwhile, as a big positive note to end what had turned into a rather sorry saga with HS2, the funding package from the Towns Fund was set to pay for the bulk of the rest of the work.

Originally it had been hoped that some £8m of Government funding would complete the restoration within Staveley’s boundaries, including constructing the second new lock (known as Railway Lock), building the TPT bridge and reinstating four more missing bridges, restoring a major clay-built embankment across the Doe Lea Valley (known as the Puddle Bank) including reinstating the aqueduct over the River Doe Lea, and restoring the associated length of channel to not far short of Renishaw.

The gap in the Puddle Bank where the new Doe Lea Aqueduct will go

On finding that only half that sum was likely to be available, and with inflation on the increase, CCT considered options for lowering its sights, and decided to concentrate on completing the first section including building Railway Lock, the TPT bridge, a second new bridge (a farm access crossing called Bellhouse Lane Bridge), a basin (formerly a junction with an old canal arm) just beyond Bellhouse Lane, and the few hundred yards of channel linking them. Following confirmation of £5.3m of funding in 2022, work on this section could go ahead. Inflation has continued to impact the scheme since then – but fortunately the grant was subsequently raised by 10 percent thanks to money transferred from other non-canal projects in Staveley which had not been able to go ahead. However, the Puddle Bank would have to wait until later – and that left CCT with another problem…

As well as a new aqueduct the Puddle Bank needs some serious rebuilding, requiring a lot more clay: firstly, the mining subsidence has left it some 3m lower than its original height; secondly, after the canal’s closure some clay was removed by local landowners and used to raise the ground level of nearby farm land which was becoming waterlogged (owing to the same subsidence); thirdly, it was built with banks much steeper than they would be if built today – in an era before modern earth-moving machinery (and before the development of soil science), the amount of dirt to be shifted was kept to a minimum at the risk of future problems with stability.

Fortunately, a local supply of clay was sourced (a former stockpile for a closed brickworks); however, it needs to be transported to the site – and there’s 300,000 tonnes of it. A route is possible for the lorries from the clay stockpile to the Puddle Bank, using the road access created for the delivery of the TPT bridge, and then running along the route of the canal bed and passing under the new bridge. That’s what George Rogers means by describing the bridge as an ‘enabling work’ – it’s allowing 15,000 20-tonne lorry loads to be delivered without crossing the TPT and footpaths, so without pedestrians or cyclists crossing the busy lorry route, and no need for control by ‘banksmen’ or temporary traffic lights. But it makes it imperative to shift it now, because once the second new bridge (Bellhouse Lane) has been built, it will block the way for lorries to drive along the canal bed to the Puddle Bank.

So even though only about 10 percent of the clay is needed for the Towns Fund supported project (for work to raise the small canal basin just beyond Bellhouse Lane Bridge, which has subsided), the Trust has had to find the money to shift the rest of it sooner rather than later. It has just approved the necessary £800,000 from its funds and the hope is that all 300,000 tonnes will be moved, 120 lorry loads a day, over a 125-day period during 2025.

There isn’t the funding to do the actual work on profiling the Puddle Bank yet – so the clay will simply be tipped to ‘rough profile’ most of the embankment. As George explains, this is actually a much more cost-effective and labour-effective (albeit slower) way of doing the job: building it slightly high and letting it settle naturally for three to four years is simpler than having to ‘heavily engineer’ it now, as George puts it to “work the clay harder” into the right shape at the start.

Meanwhile, the tendering is under way for the ‘main works’ (the rest of the construction including the new lock and bridge). The plan is to start work in autumn 2025 once the clay-shifting is complete. These main works will begin with construction of Bellhouse Lane Bridge. This will be an unashamedly modern structure formed from pre-cast concrete culvert sections. Then Railway Lock will be built – the plan is for a rather more plain concrete-lined chamber than the brick-faced Staveley Town Lock, but with blue brick lower wing walls to match the former railway bridge abutments. Finally, the channel will be completed linking the new structures to the existing length of canal and to the re-created basin at the junction with the old arm. These construction works are expected to take some nine months (and the new TPT Bridge will provide a panoramic view of them!) with completion expected in summer 2026.

Impressive though this is, it is only about a quarter mile out of the eight-mile Staveley to Kiveton length of canal that needs reopening before Canal Boat readers can cruise through from the Trent to the canal’s original terminus in Chesterfield. So, what’s on the way for the rest of the unrestored section?

It’s quite a complicated story – and it depends not only on the availability of funding for the major projects to be carried out by contractors, but also on finding other tasks suited to CCT’s capable volunteer team, who have been looking for projects to take on since finishing their part of the work at Staveley. The next such project is a length of canal leading through Renishaw. A great deal of work was done here around 15 to 20 years ago, but the section was never fully completed, struggled to hold water as a result of leaks and the lack of a decent supply, and is therefore empty and looking unkempt. However, thanks to £200,000 put aside for the canal some years ago by Derbyshire Council, £50,000 awarded by the Inland Waterways Association from its Tony Harrison legacy fund, and £150,000 of CCT’s own cash, a package of works by the volunteer team has been put together. Subject to final local authority planning currently under way, the team will complete the restoration of a ¾ mile length, including re-lining the leaking sections and installing a pumped water supply which will keep it topped up from the River Rother until such time as it’s linked up with the Staveley section.

The part restored but dry canal in Renishaw, due for completion and a water supply in the not too distant future

And that link to the Staveley section, including the Puddle Bank and a missing section of canal where it ran along the valley side north of there, is likely to be next to be tackled in the coming years. The volunteers will work from the Renishaw end, while (subject to funding) contractors will complete the Puddle Bank. Completion of this work would mean that the ‘missing link’ would have been reduced to just five miles.

Following on from that, the working party is likely to shift its attention to the north end of the Renishaw section, onto a length known as the ‘Railway Mile’ where the canal runs alongside the former Great Central Railway and continue to the edge of Killamarsh. That would further chip away at the unrestored gap, bringing it down to under four miles. It might sound like the restoration would be on the home straight – but those four miles include the two biggest challenges faced during the entire restoration.

At the east end of this length is the one and three-quarter miles of Norwood Tunnel, much of which was obliterated by coal mining and associate subsidence. We covered it in detail last month in our ‘Cruise Guide Extra’ feature, but suffice it to say that it’s going to be difficult and expensive, including: reopening the surviving short length of intact tunnel at the east end; building three new locks to raise the canal to ground level at Kiveton Waters (built for future use as a marina and used in the meantime as fishing lakes); continuing on a new surface level route around the old colliery site; dropping through three more new locks; finally passing through a new short tunnel under the M1 motorway to join the old route by the original western portal at Norwood.

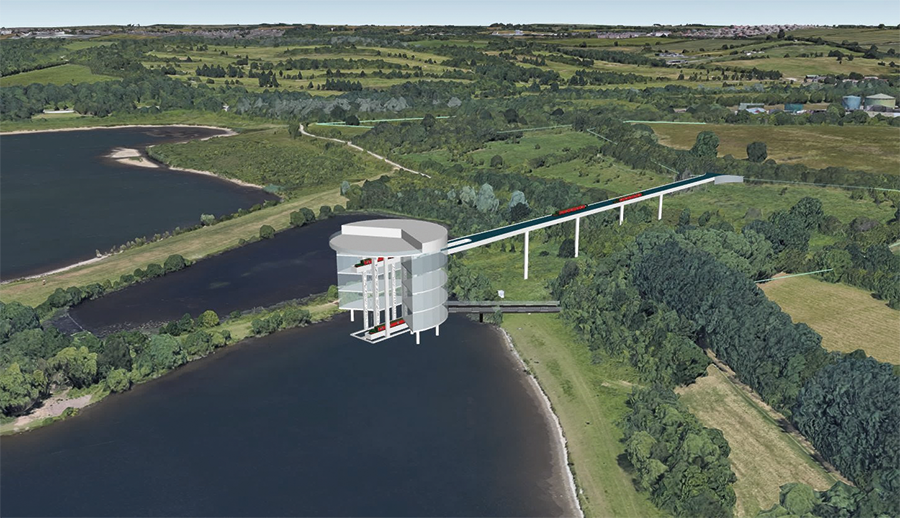

The other big challenge is a section in Killamarsh which was filled in and its route used for a new housing estate in the 1980s. A bypass route for the restored canal has been identified, but it will need some serious engineering as it involves descending to the nearby Nethermoor Lake, crossing it, and then climbing back up to rejoin the old route. That means about half a mile of new canal and two new flights of around eight locks each – or possibly one flight of locks and one boat lift.

Ever since the remarkable Falkirk Wheel boat lift was opened in 2002 as part of the restoration of Scotland’s Union and Forth & Clyde canals, and it was realised what a public attraction such devices could be (and that it’s likely that its inclusion in the project helped to swayed the decision-makers on the Millennium Fund in favour of supporting it, in a way that a flight of locks wouldn’t have done), exotic boat lifts have featured in a number of canal restoration plans. No more have yet been built, and several have been dropped as canal restorers have gone for more conventional (and cheaper) engineering, but several are still active proposals. However, the Chesterfield differs from some in that not only would it undoubtedly be a visitor attraction, but there are good engineering reasons for it too – and they’re based on the fact that lifts tend to use much less water than locks.

Just one of a number of suggested designs for a possible boat lift to provide part of the diversion around an obstructed length of canal in Killamarsh

The existing reservoirs supplying the canal’s summit at the east end of the tunnel are barely adequate to supply the locks running eastwards to the Trent; there wouldn’t be any to spare for the locks descending westwards from the tunnel. So, while backpumping at Norwood Locks would be unavoidable, construction of a lift instead of the eight new locks leading down to Nethermoor Lake would avoid the need for a second pumping system there. Combined with it being a constricted site with barely room for the locks (they would need to be built in staircases), this means that a boat lift starts to make sense.

Dealing with Killamarsh or Norwood Tunnel will be expensive – as will restoration of Norwood Locks between them. Each of the three will be a multi-million pound project, and there’s no sign of that kind of money becoming available in the foreseeable future. But does that mean it’s not worth doing anything there yet? George doesn’t think so.

At Killamarsh, a plan has been devised for the diversion, and the land has been safeguarded in local planning documents. But a close watch needs to be kept to ensure that Government targets for housebuilding don’t result in developments encroaching on this land. Alternatively, rather than just keeping a watch, it might be possible (for much less expense than actually building the new locks and bridges) to at least create isolated short sections of canal channel and towpath as local amenities, and to help preserve the line until such time as full construction can be funded.

And at Kiveton, although construction of the replacement route for the tunnel looks to be some way off, again George reckons it’s possible to do something on a smaller scale, to “get some momentum going” and “give the canal a presence without costing the earth”. So perhaps part of the new ground-level channel which will replace the middle section of the tunnel could similarly be built as a series of ponds, perhaps available for canoeing or paddleboarding, as a local amenity in advance of the arrival of canal boats from the east.

Combine those relatively minor and affordable works with having all the plans ready for future restoration, and the Canal Trust will be in a good place to act as and when major funding becomes available.

We’ve come a long way from the current project at Staveley – but in a way, it all follows on from that bridge installation in November. And at the risk of stretching a point too far, it might just lead to a final extension. A proposal some 20 years ago (in the optimistic times around the Millennium) suggested making the River Rother navigable down from Killamarsh to where it meets the Sheffield & South Yorkshire (River Don) Navigation near Rotherham. This would turn the Chesterfield into a through route, make it accessible for those unwilling to venture onto tidal water, and create a new cruising ring for those who are willing to do so. There aren’t any immediate plans to develop this idea, but it’s still in CCT’s stated aims. Maybe one day…

As featured in the January 2025 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the January 2025 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here