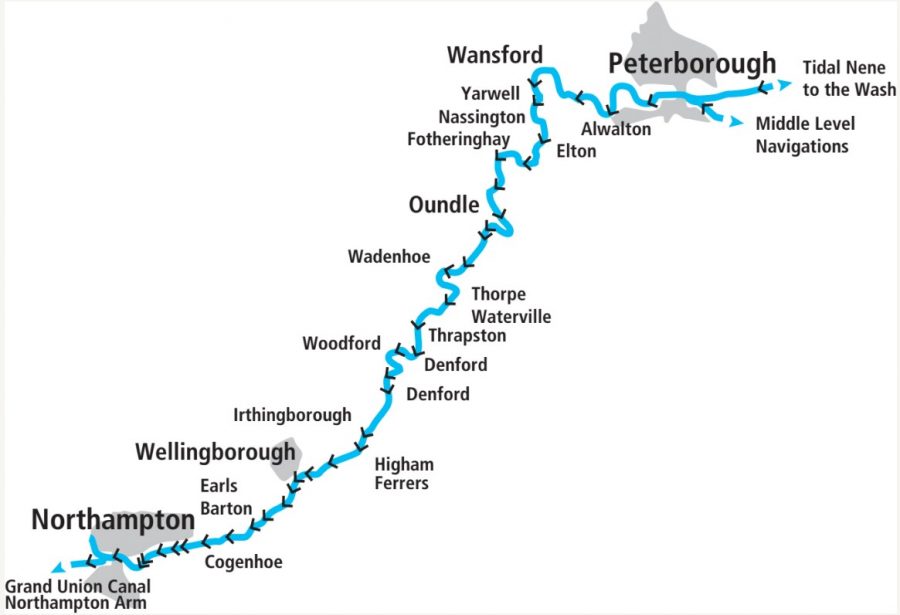

Navigable from Northampton to The Wash, the Nene is a vital link from the canal system to the Fenlands and an attractive waterway in its own right

The River Nene has in the past had a bit of a reputation among boaters from the rest of the network – and it can probably be summed up in two words: “flooding” and “guillotines”. We’re not talking about the sort of guillotine used for execution (although the subject of decapitation does come up later, as you’ll see), but the characteristic vertically rising gates at the bottom end of every lock which – in their unpowered hand-operated days – were viewed with some trepidation on account of the number of turns of the handle needed to open and close them. But these days almost all of them have been electrified, so that’s got rid of one reason for not visiting this attractive river.

And the flooding? Yes, inasmuch as all river-based waterways carry some risk of closure to navigation as a result of high water following heavy rain – but probably not significantly more so than most other rivers, thanks to the flood control work that’s been done in the past. And one part of that flood control work included the installation of the guillotine gates – and it’s thanks largely to that work in the 1930s that the river is still navigable today. So in a way, if it hadn’t been for flooding and guillotines, we might well not have been able to cruise the Nene at all. And that would be a shame, because it’s not only a lovely rural river, but it’s a crucial link in the chain of waterways linking the Grand Union Canal (and the rest of the waterways network) to the Fenlands and the Great Ouse system.

Getting there from the canal system

That chain of waterways begins with the Northampton Arm of the Grand Union. So visiting boaters will arrive on the Nene having turned off the Grand Union Main Line onto the Arm at Gayton Junction, then descended the 17 narrow locks (yes, widebeam boaters, I’m afraid those 17 locks mean you can’t reach the Nene from the southern waterways) to enter the river in the shadow of the Carlsberg brewery in an industrial area just west of Northampton town centre.

And that’s almost the only urban industry you’ll see in the journey down this almost entirely rural route. Even the rest of the route through Northampton is largely surrounded by the attractive Becket’s Park – which gives its name to the first lock. Also sometimes called Northampton Lock, this one is conventional enough with normal mitre gates (or ‘pointing doors’ as they tend to be called on the eastern waterways) at both ends. That hasn’t always been the case: until around 40 years ago it was one of three locks on the river which featured ‘radial guillotine’ gates, curved structures which swivelled upwards on pivots set in the lock walls. These had an even more fearsome reputation than the normal vertical guillotines, as they needed around 150 turns of a handle to open or close them – but two of them were rebuilt during a flood control scheme around 40 years ago.

Incidentally if you’re coming from the Canal & River Trust’s waterways and you don’t have the ‘gold’ (CRT plus Environment Agency) licence, you’ll need an EA licence before you go any further – and also an EA key for the locks on the Nene – both are available from Northampton Marina, which is accessed via the weir stream heading off to the right above the lock.

Downstream from Northampton

There are visitor moorings in the park for access to the town’s facilities, and then as the river leaves the town centre it splits into various channels, some added during the flood control works, with the navigation channel not always obvious. Look out for signs, but basically take the rightmost channel to reach the next lock, which also once had a radial guillotine bottom gate (the curved shape of the lower gate recesses in the chamber walls bears witness to this). A third lock, also with conventional gates, was newly built at the same time, bypassing one which now lies derelict on a silted-up backwater half a mile away.

Northampton Lock has conventional mitre gates, unlike most on the River Nene

As well as diverting the navigation and creating flood relief channels, the same scheme also created ‘the Washlands’ – a large area surrounded by an earth embankment, which can be deliberately flooded as a way of storing surplus water for later release at a controlled rate. The navigation passes through this embankment twice: in each case a large sluice gate can be raised by remote control to close it off if necessary – so if you happen to hear the alarm bell sound as you pass through, don’t hang around! (Seriously, it’s highly unlikely that anyone would be boating there in conditions where the sluices needed to close.)

After this heavily modified length of river, it’s a pleasant change to be back on the original course of the river, and approaching the first ‘traditional’ lock at Weston Favell. Why have I put ‘traditional’ in quotes? That’s because compared to most canal and river locks which might well date back a couple of hundred years, these are relatively modern, being a product of the 1930s…

History: from flash-locks to guillotines

Leaving Cogenhoe Lock, with its typical Nene guillotine gate

Although never really busy, the Nene had carried a modest trade from when it was made navigable in the mid-to-late 18th century – helped a little by the opening of the Northampton Arm in 1815 – until the arrival of competition from the railways in the mid-19th century. But from then on, parts of it fell into decline and decay, not helped by the large number of ‘staunches’ – primitive locks (also known as flash locks) consisting of a single set of gates – still in use on the lower lengths of the river. By the beginning of the 20th Century parts of it were virtually derelict , and in 1930 it was described as “in unparalled decay and dilapidation”.

But although by then the potential trade was small, the importance of maintaining the river for land drainage and flood control led to the establishment of the Nene Catchment Board which put in place a programme of work to rebuild the waterway. During the 1930s the staunches were abolished, and all the locks were reconstructed – as navigation structures which also served to control the water. Hence the upper mitre gates were designed so that a certain amount of water would spill over them, while in flood conditions the top gates could be chained back and the guillotine lower gate raised (known as ‘reversing’ lock), turning the lock into a large extra weir sluice. As a result, not only was flooding reduced, but a reliable and well-maintained navigation replaced a near-derelict waterway.

As built in the 1930s the guillotines (which should always be left raised when you leave the lock, whether you’re heading upstream or downstream) were raised by 100 turns of a handle. You’ll be relieved that Weston and the next few locks have all been electrified, so use your EA key to open the control box containing the pushbuttons to open and close the gate.

Cruising through an attractive reach near Earls Barton

Downstream to Wellingborough

Northampton has been left behind, and an attractive length winds its way past Billing (where the Billing Aquadrome, a leisure park formed from flooded former gravel pits, includes a marina), Cogenhoe, Earls Barton and Great Doddington. The villages are set back from the river (presumably to avoid floods), but are all with a mile or so.

Near Doddington Lock, with the old mill building in the distance

Locks occur with great regularity – the Nene has 38 locks altogether, more than any other British navigable river apart from the Thames – as we descend towards Wellingborough, where there are moorings along the Embankment for the town centre’s shops and pubs just under a mile away. Speaking of which, visitor moorings are one thing that’s been in short supply on the river – there are few official sites, a handful of ‘unofficial’ ones where mooring is permitted by permission of the landowner, but in recent years the Friends of the River Nene have been active in creating new moorings for members (similar to those on the Great Ouse provided for many years by the Great Ouse Boating Association) and it’s well worth joining the Friends, especially if you like quiet out-of-the-way moorings. You can find out more about them here.

Whitworth’s Mill, Wellingborough, destination of the last freight on the Nene

While you’re passing through Wellingborough, you can’t help but notice the large Whitworth’s flour mill buildings by the riverside: this was the destination of the last regular trade on the river, with the Willow Wren fleet of narrowboats carrying grain to the mill right up to 1969.

Former gravel pits have been a feature of the Nene valley for much of the way from Northampton, and they continue beyond Wellingborough with several of them now forming wetland nature reserves. Ditchford Lock has the last remaining radial guillotine gate on the river (and the only one in the country, until the reopening of Carpenters Road Lock in East London a couple of years ago) – but mercifully it is electrified, so no 150 turns of the handle needed any more.

Ditchford Lock has the last remaining radial guillotine lock gate on the river

Historic bridges and hand-powered guillotines

The author operates one of six surviving hand-wound guillotine lock gates on the river

The towns of Irthlingborough and Higham Ferrers face each other across the river valley, linked together by a modern road bridge but also by the old Irthlingborough Bridge, a ten arch structure probably dating from the 14th Century. It crosses just above a bend in the river, and it’s not particularly well lined-up for boats approaching, so take it carefully.

A couple of miles downriver from Irthlingborough is Upper Ringstead Lock, and here you’ll finally get to try your muscles out on one of the last manually-operated guillotine gates on the river. It’s about 100 turns to raise (and the same to lower), and it’s now operated by a large wheel (these replaced the old handles on safety grounds a few years ago). It isn’t particularly hard work, but you can imagine they got a bit tedious when there were 38 of them on the river. Now there are half a dozen, spread out between here and Warmington.

A winding length leads past Woodford to Denford where the river straightens and makes for Thrapston and Islip: another pair of twin settlements facing each other across another ancient bridge. There’s a handy pub each side of the river, and visitor moorings (with rather awkward access in longer boats) up a little inlet on the left. Parts of the bridge (known as the Nine Arches) are even older than the one at Irthlingborough, with reports of it being repaired as long ago as 1224, but with much rebuilding in subsequent centuries. It too is at a somewhat awkward angle for approaching craft. Incidentally, some say that this is where the river actually becomes the Nene, having been the ‘Nen’ since Northampton. But we’re not getting into any arguments about it…

Another five miles of meandering river lead to Wadenhoe, and something of a rarity: a waterside pub, complete with overnight moorings.

Cruising past watermeadows near Thrapston

On to the winding lower river

Whatever the truth regarding the change of name, the River’s character has begun to change a little, with the steep-sided valley now beginning to widen out, as the river passes Barnwell (with Oundle Marina sited between the two locks) to reach Oundle town. Its extravagently winding course means the Nene actually passes close to Oundle twice: at Lower Barnwell Lock, and then three miles downstream at Oundle Wharf. The latter has an ‘unofficial’ overnight mooring – with a request to vacate it early for fishing matches.

The 18th century bridge at Fotheringhay

The distinctive spire of Fotheringhay Church can be seen for some distance – there are visitor moorings in the village, plus the remains of the castle that was the subject of my earlier ‘decapitation’ reference (see inset), and a handy pub. Despite the increasingly flat countryside the locks continue to occur regularly, but beyond Warmington they’re all electric for the rest of our journey.

Steam trains and watermeadows

Listen out at Yarwell for the sound of steam trains, as it’s the first of several close encounters between the river and the Nene Valley Railway, a heritage line which has preserved and restored a section of the route which once ran all the way up the valley to Northampton. A long, gradual right hand turn leads past Wansford-in-England (there’s an old tale about how it got its name, including a haystack and a character called Drunken Barnaby) and Stibbington to Wansford Station, where the railway crosses the river, with visitor moorings in just the right place to pose a photo with your boat and a steam train. (We were lucky enough to get Flying Scotsman when we were last there!)

An attractive mooring near Wansford

The surroundings continue to level out, with flat countryside on either side and fewer locks. Water Newton Lock is accompanied (like several on the river) by an attractive old mill building, then (after crossing the steam railway again) the river skirts the edge of the Ferry Meadows Country Park. One of several lakes in the park is accessible by boat via a channel leading off on the right, with moorings for visiting the Park. The final lock on the non-tidal river, Orton Lock, is accompanied by another station on the steam railway.

Water Newton Lock and former mill

Peterborough and the Fenlands

Peterborough rather sneaks up on you, with the riversides wooded almost right into the city centre. For visitor moorings and a chance to visit the city with its cathedral and other attractions, carry on through the railway bridges and the Town Bridge, and you’ll see the Embankment stretching some distance on your left with plenty of mooring space.

This isn’t the end of the river by any means, but it’s as far as many inland boaters travel on it. The reason is that they’re heading for the start of the route via the Middle Level Navigations across to the River Great Ouse, which bears off right under a railway bridge about half a mile past the Town Bridge.

Peterborough bridge, with the old customs house on the right

Inland boaters continuing on the final five miles of the non-tidal Nene beyond Peterborough will probably be doing so for one of two reasons: either as the first stage of an adventurous trip down the tidal river and across the Wash to the River Witham; or simply to complete their cruise of the entire non-tidal river to turn around before the start of the tideway at Dog-in-a-Doublet Lock (and perhaps stop for a drink at the pub of the same name). They’ll find that the river has undergone a complete transformation, from a natural meandering and sometimes rather narrow river to a wide, straight fen-like channel, clearly of artificial construction.