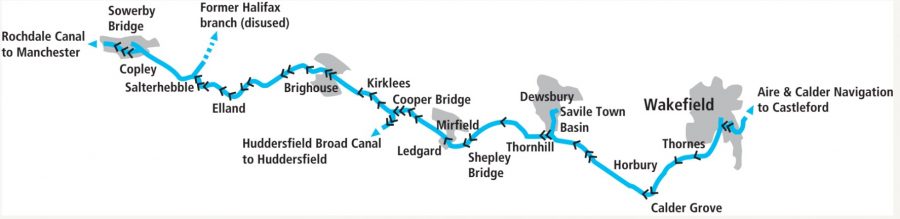

Part natural river and part artificial canal, the fascinating Calder and Hebble navigation climbs from Wakefield into the Yorkshire hills to link to the trans-Pennine canals. Read our guide to the best pubs along the Calder and Hebble here

Our river-based waterways come in variety of forms. On the one hand there are what I would term ‘navigable rivers’, like the Thames or the Severn; by contrast, Yorkshire’s Calder & Hebble Navigation is more what would be classed a ‘river navigation’. Am I being pedantic? Possibly. Is this an official distinction? Possibly not. But when, in its upper reaches, you travel for six miles through 12 locks without ever cruising along a single yard of actual river, you realise you’re in a rather different style of inland waterway when compared to, say, the Severn, where mile upon mile of natural river reaches are interrupted by just the odd short lock cut and adjacent weir.

Our river-based waterways come in variety of forms. On the one hand there are what I would term ‘navigable rivers’, like the Thames or the Severn; by contrast, Yorkshire’s Calder & Hebble Navigation is more what would be classed a ‘river navigation’. Am I being pedantic? Possibly. Is this an official distinction? Possibly not. But when, in its upper reaches, you travel for six miles through 12 locks without ever cruising along a single yard of actual river, you realise you’re in a rather different style of inland waterway when compared to, say, the Severn, where mile upon mile of natural river reaches are interrupted by just the odd short lock cut and adjacent weir.

The Calder & Hebble is still very much a waterway based on the River Calder rather than a completely independent canal, though. And as the many flood-locks (and one or two news stories in the last couple of years about flooding) remind us, it’s subject to the changes in water level which are a feature of river waterways. But right from its construction in the 1760s, it relied on a large proportion of artificial canal sections or ‘cuts’ to create a navigation based on a relatively small and steeply-falling river. And over the years, as we shall see from the signs still visible, the canal sections were extended and joined together, ultimately adding up to more than half of the waterway.

This is a feature that it shares with its bigger neighbour, the Aire & Calder Navigation, which it meets in the city of Wakefield – and that’s where we’ll start our journey.

Leaving a canal section to rejoin the River Calder in Wakefield

Start at Wakefield (joining from the Aire & Calder)

Until 2001, Wakefield was the only point where boaters from the rest of the national network could join the Calder & Hebble. The trans-Pennine Huddersfield Narrow and Rochdale canals had been abandoned in 1944 and 1952 respectively and were still under restoration (and widely regarded for some years as a rather unlikely prospect for reopening), while the Calder & Hebble survived as a rather out-of-the-way dead end. All that has changed now, with the C&H forming part of two trans-Pennine routes, and (for the energetic who fancy almost 200 locks and two Pennine crossings in around 70 miles) the South Pennine Ring. But it’s still not a busy waterway.

One thing you’ll notice soon after you join it from the Aire & Calder at the curiously-named Fall Ing Lock (‘ing’ is a local name for a water meadow) is that there’s a change of scale. The A&C was continuously improved over the centuries, its original 54ft by 14ft locks progressively rebuilt or bypassed by new cuts, leading to today’s wide channels and modern electrically operated locks capable of taking commercial barges up to 180ft by 17ft 9in, with some hope of a revival of large-scale freight carrying. Meanwhile the Calder & Hebble has remained largely restricted to its original dimensions of 57ft 6in by 14ft. Its locks remain manually operated (with a uniquely manual way of opening paddles, as we shall see), and it retains much of its historic character; on the downside, it carried its last regular cargo 40 years ago.

But note that I said “soon after you join it” and “largely restricted”. Although the navigation didn’t see the sort of enlargement and modernisation enjoyed by the Aire & Calder (the C&H coming under control of the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway for some years in the 19th century didn’t help – you can still spot small stone ‘LYR’ boundary stones at various places along the towpath), in later years a lease by the A&C led to enlargement of the first section. This meant that boats up to 120ft by 17ft 6in could get as far as Broad Cut, and you will still sometimes see these dimensions quoted as current – but don’t trust them, because most of the extra lock gates added during the lengthening have fallen into disuse and been removed.

Fall Ing Lock is plenty long enough for a full-length narrowboat even without the extra gates (which do still appear to be functional), and leads to a cut which skirts Wakefield on the south side, with moorings available to visit the city. Passing the modern Hepworth gallery, the cut ends with the typical Calder & Hebble feature of a flood-lock to protect the cut from high water on the next river section. There are many such flood-locks (or in some cases single sets of flood gates) where you will normally find the gates open and cruise straight through; if they have been closed that usually means the river is in flood and you are advised to find a safe place to moor on a non-river section and wait for levels to fall.

Flood locks and flood gates are a feature of the waterway. Normally the gates are open and you cruise through – unless the river’s in flood, in which case you’re advised to find somewhere safe to tie up

Turn left to rejoin River Calder

As you leave the cut, the navigation turns left to rejoin the River Calder; to the right is a short dead-end leading to Wakefield Weir via some attractive old waterside warehouses and in the distance a boatyard with an assortment of interesting old craft moored up.

Gradually leaving Wakefield behind, the first couple of miles of the navigation are characterised by broad river reaches meandering across a wide valley. At Thornes Locks (they used to be duplicated), the surviving chamber has now lost the extra bottom gates which were added when it was lengthened, but I can vouch for the remaining chamber being just long enough to take a full-length (71ft 6in) narrowboat. It’s also the first lock where you will need the legendary Calder & Hebble handspike…

Once found on other north east waterways and beyond, the type of paddle gear on the Calder & Hebble locks is now the last in the country which is operated not with a windlass but with a length of timber called a handspike. Simply insert the handspike into one of four holes in a small capstan-like wheel forming part of the paddle gear; apply muscle power to move the handspike, using it as a lever to rotate the small wheel by a quarter-turn, which raises the paddle by a short distance; remove the handspike (having checked that the ratchet is in place) – and repeat.

Opening the lock paddles with a handspike: somewhat laborious but a unique historic feature of the Calder & Hebble

Although it’s not quite as laborious as it sounds, it’s no real wonder that it hasn’t survived elsewhere – but many (including the author) would have been very sad to see this odd little quirk of waterways heritage disappear. Alongside these paddles there are also other rather more conventional designs including some sturdy enclosed metal gear and some monumental ground paddle gear consisting of two separate paddles enclosed in a single massive iron housing.

Incidentally if tempted to make your own handspike, bear in mind that this is another area where quoted dimensions can be inaccurate: various sources quote 4in by 2in (by about 3ft long), but I can vouch for that being too big to fit. It’s more like 3in by 2in – or you can just buy one from a local boatyard.

The curiously named Figure of Three Locks, rebuilt after flood damage in recent years

Broad Cut Low Lock and the many miles of artificial waterway

Broad Cut Low Lock is just a little shorter than Thornes – it too has lost its extra bottom gates, and our full-length narrowboat just failed to fit the remaining chamber; but anyway, the next lock was never lengthened, and although there was some piecemeal enlargement of some locks beyond, you won’t get much further in anything much more than around 58ft.

This is the first of the long sections of artificial waterway: almost six miles and seven locks until the navigation rejoins the Calder. The useful Horbury Bridge village is followed by the curiously-named Figure of Three Locks – and one of the more curious things about them is that there are actually only two locks. The jury’s still out on whether this was because there were once three locks altogether (the third one was a side-lock into the River Calder, a relic from when the navigation used more of the natural river), or because the river makes a series of bends which form a rather badly-drawn figure ‘3’.

More seriously, these locks bore the brunt of the early 2020 floods in the Calder valley, resulting in damage to the lower lock, the associated overflow weir and the ‘island’ between them which took over a year to repair.

Just as it skirted the south side of Wakefield, the navigation runs around the south of Dewsbury – but in this case a short arm takes boats to Savile Town Basin, three quarters of a mile closer to the town centre and home to a boatyard, moorings and a pub. It’s actually another remnant of the waterway’s earlier route, bypassed by later improvements.

The two Thornhill Locks are separated by an almost circular pound

The junction with the arm is followed immediately by Thornhill Double Locks which are closely spaced, separated by an almost circular pound. The usual floodlock and the aptly-named Long Cut End Bridge indicate the navigation’s return to the River Calder – but not for long. Greenwood, Shepley Bridge, Battyeford and Cooper Bridge locks follow, each on their own separate cut separated by short lengths of river, as the climb into the Pennines steepens. Mirfield is a useful town for shops and pubs.

At Cooper Bridge the Huddersfield Broad Canal branches off to the south, climbing through nine wide-beam locks to Huddersfield, where it makes an end-on junction with the trans-Pennine Huddersfield Narrow Canal. It’s a slightly curious junction layout: to reach the Huddersfield Broad Canal, you turn sharp left at the end of the Cooper Bridge Cut, heading back down the weirstream towards Cooper Bridge weir before bearing off to the right to enter the first lock on the canal. If that sound a bit hairy, don’t worry – the weir is protected, there’s a landing stage, and it isn’t a sharp turn into the lock.

Climbing the pair of locks on the approach to Brighouse, after leaving the river for the last time

Leave the Calder for the last time at Brighouse Locks

Meanwhile continuing on the Calder & Hebble, what was a broad, shallow valley at the start of our journey is now increasingly deep, narrow and steep-sided, with dramatic views as we pass Kirklees and reach Brighouse. It’s still over six miles to the end of our journey, but at Brighouse Locks we leave the River Calder for the last time, with the remaining length consisting entirely of artificial canal (although that hasn’t always been the case – you can see signs of old locks where it once joined the river). Two locks (again separated by a wide, almost circular, pound) climb into Brighouse town, with the canal running conveniently through the centre of the old mill town. Frequent locks continue the climb, with the canal separated from the river by just a narrow wall in places, as Brighouse is left behind and the waterway approaches Elland, another textile mill town.

You might spot another heritage feature near some of these locks – in fact, exactly 100 yards on either side of them. Small stone markers similar to milestones, with ‘100 yards’ carved into them, appear to have performed the same function as the better-known ‘Lock Distance’ posts on the Grand Union Canal: an attempt to settle disputes by boaters approaching from opposite directions about whose right it was to use the lock first. Whoever passed the stone first could claim the lock.

Cruising on a canal section near Elland

Elland has been another victim of the storms of recent winters, with two bridges over the navigation having to be completely rebuilt following flood damage. It’s followed by another length running close beside the Calder before the final three locks at Salterhebble raise the navigation high up the valley side. They’re a very attractive flight in a spectacular hillside setting, but with a curious zig-zag layout. The first lock (fitted with an electric powered guillotine bottom gate, made necessary when the adjacent road bridge was widened over the lock tail) is followed by a sharp 90 degree right hand bend leading into the second lock, then a sharp dog-leg to the right leads into the top lock, which is followed by a T-junction with a short arm (a remnant of the abandoned Halifax branch) to the right, and the through route to the left. This results from yet another of the many modifications to the Calder & Hebble over the years: originally the top two locks formed a staircase pair, but they were rebuilt as two singles to save water – which took up more room, and meant adding a dog-leg to create enough space to pass boats between the locks.

Approaching the terminus basin at Sowerby Bridge

Finish at Sowerby Bridge

The final two miles follow the wooded valley side as the waterway nears its end at Sowerby Bridge. Just before the terminus, the Rochdale Canal turns off sharp left to begin its Pennine crossing, leaving the Calder & Hebble to terminate in a basin surrounded by a fine range of warehouses – and home to a boatyard, hirefleet and other new businesses which have brought new life to the old buildings. It’s a fine end to our journey, a complete contrast to the broad river at Wakefield, and a good place to stop before continuing your journey over the Pennines.

Image(s) provided by:

Martin Ludgate