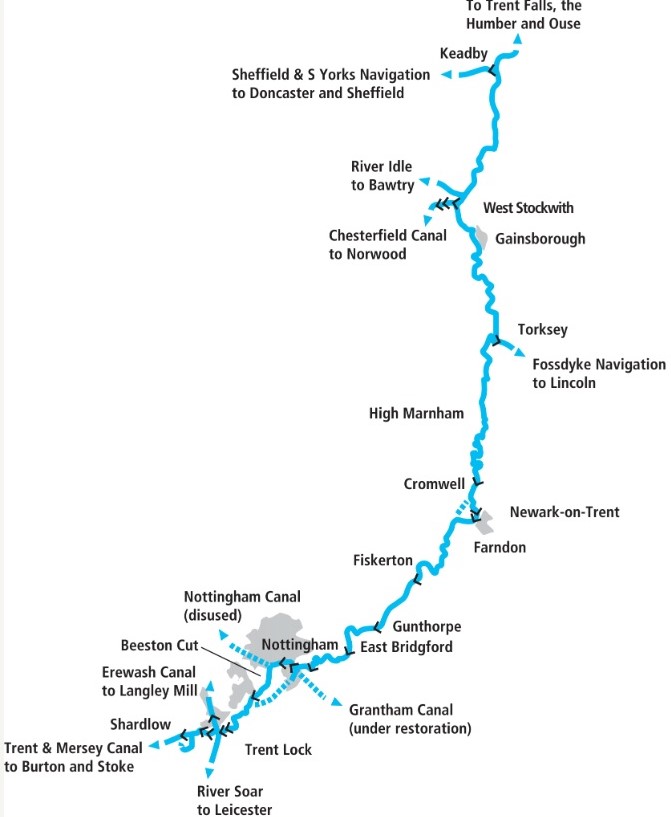

The Trent forms a useful link between the Trent & Mersey Canal, River Soar and other waterways – but it’s more than that, it’s an interesting and attractive route to cruise

Don’t be daunted

Some boaters view the River Trent with a certain amount of trepidation – especially in its lower tidal reaches. And while it’s reasonable to show some respect to a tideway with sometimes fast-flowing currents, limited places to stop, and sandbanks and other obstacles to be aware of, these days there is a great deal of information to help inland boaters to take on safely what may seem like adventurous trips.

But further upstream on the non-tidal reaches there’s less to be wary of. If you simply treat it with the same consideration that you would any river – allow for currents, avoid shallows on the inside of bends, and be wary of navigating after heavy rain – it not only provides a safe and useful link between other waterways, but an often attractive and interesting waterway in its own right.

The upper reaches

And one of the interesting things about it is its somewhat complicated history, with what were originally three different waterways making up its uppermost 12 miles from Derwent Mouth to Nottingham.

Those weren’t always the uppermost navigable reaches: the river was once navigable (albeit not always easily) all the way up to Burton upon Trent. But the arrival on the scene of the Trent & Mersey Canal, and its promoters’ decision to end their waterway at a junction with the Trent at Derwent Mouth rather than Burton, soon established Derwent Mouth as the effective head of navigation of the river, with trade dying out on the upper reaches to Burton.

You’ll arrive there from the Trent & Mersey Canal at a four-way junction. To your left, the River Derwent heads for Derby: it too was once navigable after a fashion, but its role as a waterway link to Derby was later provided by the Derby Canal (abandoned in 1960 but now being restored). To your right, the upper Trent heads off under a long towpath bridge towards Burton – but these days boats only use the first mile or so as a dead-end leading to Shardlow Marina. And straight ahead is the Trent heading on downstream under a bridge carrying the M1 motorway.

The paired Sawley Locks

Boats aren’t on the river for long, because after barely half a mile it leads off over a weir to the left while the navigation continues straight ahead into Sawley Lock Cut. A flood lock at the start of the cut (usually found with the gates open at both ends – if not, it’s likely to indicate that the river is in flood: navigate with caution and if in doubt find somewhere safe to tie up) is followed by a large marina and them by the paired Sawley Locks. Slightly larger than the wide-beam locks you’ll have passed on the eastern Trent & Mersey, these are mechanised and operated using a Canal & River Trust ‘Watermate’ (sanitary station) key.

The river rejoins below the lock for a mile leading to Trent Lock, a major waterway junction. To the left, a sharp turn into the Erewash Canal leads to the actual Trent Lock, the first of 15 in 12 miles as the canal climbs to Langley Mill (and further, as and when the Friends of the Cromford Canal’s restoration plans come to fruition). Meanwhile the main channel of the Trent bears slightly to the right, leading towards Thumpton Weir: take this but then turn immediately right for the start of the River Soar and the Grand Union Canal Leicester Line leading southwards through Leicester. But we won’t take either of these turns; instead we’ll bear slightly to the left to stay on the Trent Navigation and enter Cranfleet Cut, once again protected by a flood lock that’s usually open at both ends.

The great waterway junction at Trent Lock

This finally leads onto the first moderately long stretch of river: four miles of gently winding, tree-lined channel leading past Attenborough Nature Reserve (it’s named after the nearby village, rather than the famous TV naturalist – although it was in fact opened by him!) to reach Beeston. Here boats leave the river to enter the Beeston Cut, historically built as a separate waterway. Time for a short history lesson…

A complicated history

The Trent had been navigable as a free-flowing natural river since long before the canal era, but suffered from the usual problems of unimproved rivers – too little water for boats to float in in summer, and too much for safe navigation in winter. There was no towpath so boats were hauled by gangs of men – sometimes up to ten to haul a small ten-ton boat. Improvements were gradually made – two locks were added at Newark in 1773, another at Sawley in 1793. But the length through Nottingham remained a problem, with the passage through Nottingham’s Trent Bridge being regarded as particularly hazardous.

Meanwhile work had begun on building the Nottingham Canal. It ran north from the Trent just east of central Nottingham, then turned west to run through the city centre to Lenton, before turning northwards again and climbing through a series of locks to meet the Cromford and Erewash canals at Langley Mill. At Lenton it passed within a couple of miles of the Trent at Beeston: building a short canal between the two would create a bypass by which Trent traffic could avoid the dangerous river passage through Nottingham. All that remained was a certain amount of haggling about who would build it – the Trent Navigation Company wanted it built, but didn’t want anyone else other than them to build it and get the benefit of the tolls. The new canal, known as the Beeston Cut, opened in 1796. So today, boats pass through Nottingham using the Beeston Cut and the surviving eastern two and half miles of the Nottingham Canal (the remainder, running from Lenton to Langley Mill, closed in 1937).

The Beeston Cut meets the Trent at Beeston Lock

Boats enter the Cut via Beeston Lock, a flood control lock with no more than a few inches of difference in level. Note the signs saying that the paddles should be left with the red one open at each end of the lock, to keep the Cut supplied with water from the river. Note also the remains of an old lock which used to lead back into the river below Beeston Weir – this was built to allow local traffic to continue after the Cut took over the through trade.

The passage through Nottingham

The Cut takes a straightish course through the outskirts of Nottingham, passing housing and industry (including the site of the former Raleigh bicycle works) on its way to Lenton. There’s little there to indicate that this was a junction, and that boats are leaving the Beeston Cut and joining the Nottingham Canal – the first part of the old line to Langley Mill has been largely obliterated (although further north there are surviving lengths where the towpath is walkable and worth exploring). Well, actually there is one thing: the local place name ‘Lenton Chain’. This commemorates the chain which was padlocked across the canal by the Trent Navigation Company on Sundays to prevent any traffic from passing. This was because the Trent Navigation Company disapproved of trade on the Sabbath; by contrast the ungodly Nottingham Canal Company allowed it to pass.

The canal is now approaching the centre of Nottingham, where it’s surrounded by an assortment of modern urban developments and impressive historic canal warehouses, with canalside pubs and the city’s shops and attractions close by.

Nottingham’s old canal warehouses have been redeveloped

Return to the River

After a sharp right turn amid new developments, the canal heads south alongside a main road, through a series of double-arched bridges (take the left span in this direction) past what’s currently a somewhat unkempt area to reach Meadow Lane Lock, which leads back into the River Trent. Here we bear left to rejoin the river, but that isn’t the only option. It’s possible to turn sharp right and head up the river for a short distance, passing through Trent Bridge to take advantage of attractive visitor moorings on the south bank. And it was once also possible to cross the river and enter the Grantham Canal. This closed in 1936 but the Grantham Canal Society is working to reopen it. However although the first lock in the centre of Nottingham was restored back in the 1970s (and you can still see it), this was largely to publicise the restoration plans rather than with a view to eventually reopening it: the loss of a section of canal under a major 1970s road scheme means that the eventual restoration of the canal will almost certainly involve a diversion joining the Trent some distance further downstream.

Rejoining the Trent on the east side of Nottingham

The river may not have got a great deal wider in the six miles or so since we last saw it at Beeston, but some of the boats certainly have. Up to now, the locks we’ve passed have been only a little larger than typical broad-beam canal locks, but from here onwards it’s a different matter. Over the first half of the 20th Century the waterway below Nottingham was enlarged, with new locks built to dimensions of 180ft by 30ft, designed to take a tug and three barges. Sadly no such commercial freight traffic has used it regularly for some decades, but plenty of large leisure craft take advantage of the big locks. As you’ll be relieved to find out when you reach the first one, Holme Lock, they’re all power operated, and if there aren’t keepers on duty they can be boater-operated by CRT key.

Walkers beware

Incidentally anyone following the river on foot should note that there isn’t a continuous towpath – although the guidebooks show a riverside path, they also indicate that more than once it changes side with no bridge (including just downstream of Holme), leading to long detours. There is, however, a waymarked long-distance path called the Trent Valley Way which follows the river rather less closely (up to a couple of miles away at times) all the way from Beeston to the Humber estuary.

Passing under Radcliffe Viaduct

Up to now the Trent has flowed through a flattish landscape with valley sides mainly set some distance back from the waterside, but that changes below Holme Lock. Radcliffe on Trent lives up to its name, with a steep wooded hillside rising to some height from the water’s edge on the east bank. The Trent Valley Way follows the cliff top, with occasional good views over the river.

The Trent Valley Way provides a fine view of the river from the top of the cliff at Radcliffe

Stoke Bardolph is a small riverside settlement with a rare waterside pub whose name – the Ferry Boat Inn – gives a clue to its history. Today, with the disappearance of the old river ferries, there are some long gaps between crossing points: we haven’t seen a road bridge in the six miles since Nottingham, nor are there any in the next four to Gunthorpe.

Approaching the Ferry Boat Inn, on a quiet stretch of river near Stoke Bardolph

The large locks continue at intervals of a few miles; the one at Gunthorpe is a popular stopping point with moorings and a short walk to several pubs and restaurants along the riverbank. Steep hillsides continue to follow the east bank with the Trent Hills accompanying the river for some miles.

Diversion via Newark

Fiskerton and Farndon provide pubs and moorings (not always easy to find on rivers) as the hills are left behind and the river follows a meandering route to Averham Weir, where it splits into two. The larger unnavigable channel passes over the weir and disappears off north westwards, while the narrower branch bears right and carries the navigation route eastwards towards Newark. The narrow channel merges with the unnavigable River Devon as it winds its way into the town.

On the narrow reed-fringed eastern channel of the Trent leading to Newark

Newark is the first sizeable place on the Trent since Nottingham, and this is reflected in its importance as a riverside town both historically and today. The waterway passes a marina on the approach to the town, a former warehouse still bears the name of the Trent Navigation Company, and one of the Canal & River Trust’s main engineering workshops is based there, with a drydock where workboats are maintained. Below Newark Town Lock the riverside ruins of Newark Castle, the historic seven-arch Newark Bridge and the Leicester Trader heritage barge complete an attractive waterside scene.

Newark Town Lock with the castle ruins beyond

To the tideway

For boaters not planning to venture onto the tidal river, Newark makes an attractive and interesting destination; however for those travelling further (or simply wanting to explore the entire non-tidal reaches) there are another five and a half miles to cruise. Leaving the town via Newark Nether Lock and a series of road and railway bridges, the navigation rejoins the other branch of the river which we last saw at Averham Weir. A series of sweeping bends as the river enters flatter countryside takes us past North Muskham (with moorings, shop and pub) to reach Cromwell Lock.

Beyond here the river is tidal, a rather different waterway, and one very much to be treated with respect. However it’s also a very useful route to the Yorkshire waterways, and it’s the only way to get to the Chesterfield Canal and (for most boaters) the Fossdyke and Witham navigations too. And for experienced boaters in appropriately reliable and suitably equipped inland craft, it’s perfectly safe to navigate – and these days there are are plenty of resources to help you, including the Trentlink Facebook group (it’s a private group so you’ll need to join it) and the book Narrowboat on the Trent which you can buy from the Chesterfield Canal Trust’s website.