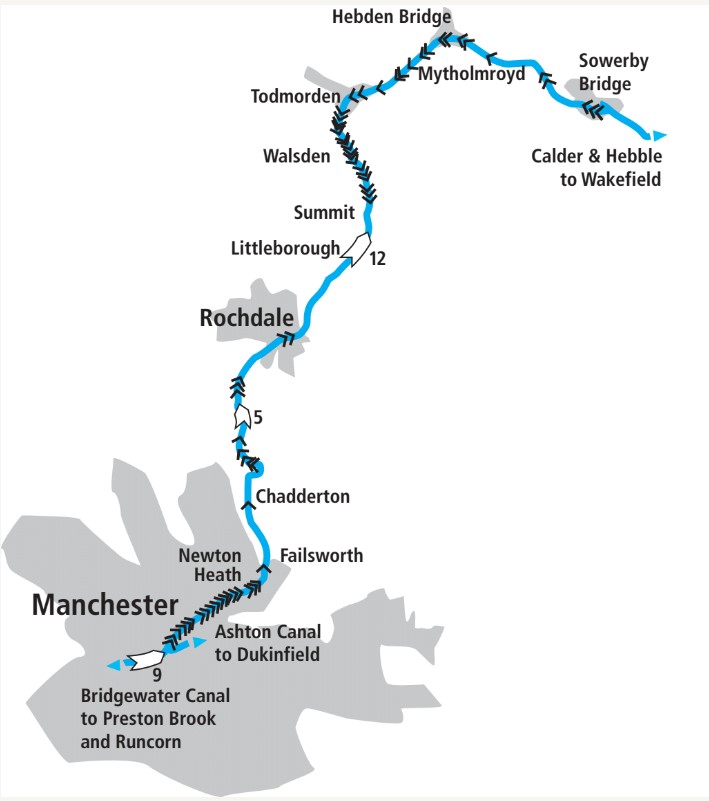

The Rochdale Canal climbs from the heart of Manchester to cross the Pennines amid spectacular moorland scenery before descending through Yorkshire mill towns

Our cruise through the Rochdale Canal from Manchester to Sowerby Bridge in Yorkshire begins with a mile of urban waterway through Manchester’s city centre. And for many years that mile was all that there was of the Rochdale Canal. The magnificent trans-Pennine section had been abandoned in 1952 after the last freight traffic died, and all that remained was the short urban section (known as the ‘Rochdale Nine’ on account of its nine locks) linking the Bridgewater Canal to the west of Manchester with the Ashton Canal to the east.

Even that mile-long link was nearly lost, along with the Ashton and lower Peak Forest canals. The long and ultimately successful campaign in the 1960s and early 1970s to save what had been christened the ‘Cheshire Ring’ is one of the stirring stories of the waterways movement and the early canal restoration era. It culminated in the reopening of the Ashton and Peak Forest in 1974, followed by the Rochdale Nine a couple of years later.

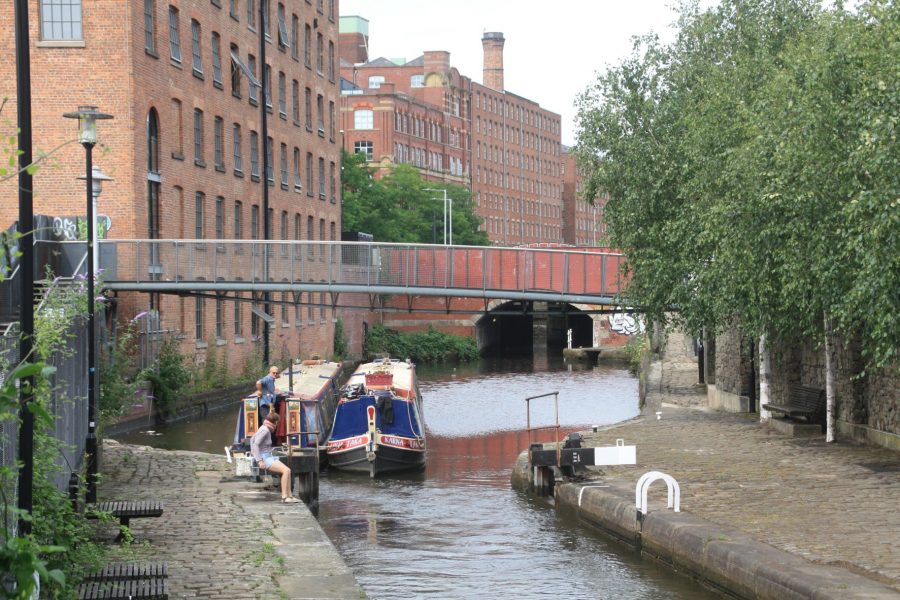

Climbing the Rochdale Nine locks through the heart of Manchester

Up the Rochdale Nine

The ‘Rochdale Nine’ still fulfil that role as a connecting link in the Cheshire Ring. They begin with Lock 92, Duke’s Lock, which lifts boats from the Castlefield complex of basins which form the terminus of the Bridgewater Canal onto the start of the Rochdale. It’s a slightly odd lock – it seems to take forever to fill and empty, and the bottom gates are operated not by pushing on the balance beams, but using a windlass to operate a winch which pulls the gates with via a chain. Incidentally its name refers to the Duke of Bridgewater – who was initially reluctant to let the newer Rochdale Canal connect to his Bridgewater Canal. When he did finally agree to it (he realised that turning away through trade from the trans-Pennine canals wasn’t a good idea), he insisted on his own men building the connecting lock.

Duke’s Lock is followed by the remaining eight locks making up the city centre ‘Nine’, as the canal climbs through what was (at the time that its future was in the balance) a rather grim inner-city area, but is now buzzing with nightlife and surrounded by bars and restaurants. It leads on up to the colourful Gay Village, and through a mysterious cavern-like covered length (complete with an underground lock) buried under a 1960s tower block, to emerge blinking into the daylight at Ducie Street Basin.

Here, boats following the Cheshire Ring turn sharp right through a bridge that forms the start of the Ashton Canal – and from the next quarter-century after the reopening of the ‘Nine’, that was all they could do. The Rochdale Canal leading straight ahead was not only abandoned, but the next few miles had been reduced to an unnavigable ‘water channel’ by filling it in to just a few inches deep in the interest of preventing drownings. All that changed in the 1990s when the efforts of the Rochdale Canal Society, which had been beavering away since the 1970s on restoring sections of canal further north and fighting for the canal’s future when new road schemes threatened it, were rewarded with the announcement of a major grant from the National Lottery’s Millennium Fund.

There were problems to overcome on the way. Not least when the canal’s owners (a property company who made money from using the largely filled-in Ducie Street Basin as a city centre car park) tried to push up the sale price of the canal, which up to then had been a not terribly valuable asset. Not to mention a landowner who was so opposed to the canal opening through his property that he jumped in and swam in front of the dignitaries’ boat at the official opening! But the restoration was completed and the canal reopened throughout in 2002.

The canal leaves Manchester city centre accompanied by a series of old cotton mill buildings

Climbing out of Manchester

You can still see some signs of rebuilt locks and new bridges as the canal heads north eastwards out of the city centre, past a succession of impressive old mill buildings recalling Manchester’s cotton industry. That isn’t the only industry that’s left its mark on the canal – this was a coalmining area too, and mining subsidence has affected the levels. Lock 77 has had to be raised to counter this, and has ended up as the fourth deepest lock in the country with a rise of over 15ft. Speaking of locks, they keep up a steady climb with little respite, making this length rather hard work for small crews as the canal gradually raises itself through Manchester’s suburbs of Newton Heath and Failsworth.

Reopening the canal through Failsworth was a notable achievement, as it involved the demolition of a supermarket which had been built on the route after the canal closed – which was done during the final six months of the restoration. I remember it well, having been on a site visit in winter 2002 and thought “That’ll never be open in six months!” It was.

Failsworth Top Lock marks the end of the climb (at least for now). It’s followed by another reminder of the canal’s restoration, and a significant victory by its supporters, as the canal crosses the M60 Manchester orbital motorway via a series of tight bends and a tunnel-like culvert under the road. It certainly isn’t a thing of beauty, and the towpath rather inconveniently leaves the canal for some distance. But it was a remarkable achievement to get provision made for the canal’s future restoration at all at a time several years before the National Lottery’s millions were available to make it a reality.

Into the countryside

The rather stereotypically northern sounding Grimshaw Lane liftbridge is an unusual vertical rising structure, operated by boaters using a Canal & River Trust ‘Watermate’ (sanitary station) key. But in reality the canal is starting to look considerably less grim as the almost unremittingly urban surroundings which have accompanied it ever since Duke’s Lock finally start to give way to some open country as Chadderton is passed.

As Manchester is left behind, the canal gradually becomes more rural

Look out for the Irk Aqueduct. It isn’t a particularly impressive structure, but it’s pretty much the only notable aqueduct on the Lancashire side of the canal. And it’s caused the canal’s owners some headaches over the years with major embankment collapses alongside the aqueduct, both in recent years and back in 1927. It’s followed by a flurry of locks as the climbing begins again, with a set of four followed by a flight of six climbing to Slattocks. There’s further evidence of the challenges faced during the canal’s restoration in the form of a culvert under the M62 motorway which carries a floating towpath alongside the navigable channel. The reason for this curious arrangement is that the motorway having been built during the long years of canal closure, it blocked the channel with no provision for navigation. Rather than try to fund a new motorway bridge, the restorers diverted the canal through this existing bridge which had been built to carry a former farm lane. But this was too narrow to take both a 14ft wide navigation channel (this canal was built for wide boats) and a towpath. Reluctant to either restrict the restored canal to 7ft beam narrowboats, or to fail to provide a towpath for walkers, they hit on the ingenious idea of building the towpath from floating pontoons so that it can be floated out of the way when a widebeam boat needs the full width.

Another new concrete ‘tunnel’ dating from the canal’s restoration carries it under the A627 and into the outskirts of Rochdale, where the canal skirts the old mill town’s eastern fringes, with the town centre and its useful shops a little way to the west of Bridge 60. It used to be served by a short arm of the canal, but it has long been derelict – although there have been proposals for a revival.

Views of the Pennines as the canal reaches Littleborough

Crossing the Pennines

Leaving Rochdale behind, for the first time there’s a sense that we’re on a trans-Pennine canal, with glimpses of the hills in the distance. As if to shatter this illusion, the canal promptly passes under a bridge carrying a tramway, reminding us that we’re still within the further reaches of Manchester’s transport networks!

Passing Smithy Bridge, the canal approaches Littleborough, where the hills close in on both sides and the final climb up the River Roach valley begins. A closely spaced series of 12 locks leads up to the summit, which it reaches at the appropriately-named village of Summit, complete with the canalside Summit Inn. A sign proclaims that West Summit Lock, the last of the long climb, is “the highest broad lock in England”. Well, call me a pedant, but wouldn’t the lock at the far end of the summit have an equal claim to fame?

On the final climb to the summit

The canal’s summit is dramatic, as the valley cuts through the Pennines, but it’s also short, which has been a headache for the canal’s operators at times. At just three quarters of a mile long it doesn’t hold a huge reserve of water, so it can be subject to fluctuations in level; it also doesn’t give boaters much time to relax before the locks begin again. The initial descent is as steep as the climb, with lock after lock lowering the canal through splendid Pennine valley scenery to Walsden and Gauxholme. The canal is squeezed into the valley alongside a railway and a main road, leading to some interesting engineering where they meet. This includes viaducts, an impressive castellated railway bridge over the canal, and ‘The Great Wall of Todd’, an immense blue-brick retaining wall supporting the railway on the valley side high above the canal on the approach to Todmorden.

On the descent from the summit into Yorkshire

The descent into Yorkshire

Lock 19 is another curiosity: during the time that the canal was closed, the main road was widened over the tail of the lock, leaving no space to reinstall conventional lower lock gates in their original position. But a small aqueduct under the head of the lock meant it couldn’t be extended at that end either – and the restorers were keen not to reduce the maximum boat length below the 72ft that it was built for. So they installed a vertical guillotine type lower gate, which took up less space. It’s power operated using a Watermate key.

Todmorden is a fine old mill town with an interesting situation at the junction of two valleys and historically (until the boundary was adjusted in the late 19th Century) at the point where Lancashire and Yorkshire met. The town hall sat symbolically on the exact boundary with half of the building in each county.

A tall mill chimney marks the canal’s arrival in Hebden Bridge

The Calder Valley’s mill towns

So far, the descent in the Yorkshire side has mirrored the climb on the Lancashire side, but the final section has no close parallels with the climb out of Manchester. Rather than a succession of locks running through an urban area, the canal descends slightly more gently down the upper Calder valley, between splendid hillsides, often wooded, and separated from railway and road by the infant River Calder. But one feature it does share with the Manchester end is mills. Built of stone rather than brick, there are some fine reminders of the woollen industry as we approach the next attractive old mill town of Hebden Bridge, which since the decline of industry has reinvented itself as a centre for arts, creativity and alternative living.

Passing through the old mill village of Mytholmroyd

Tuel Lane Lock, the deepest in the country, leads down into a new tunnel as the canal nears its terminus in Sowerby Bridge

An aqueduct crosses the Calder in the town centre, then a long, curved, tunnel-like bridge (best to give a blast on the horn in case there’s anything coming) takes the canal under the main road on its way out of town. The descent slows still further after Mytholmroyd, with just two locks in the next four miles or so. Sowerby Long Bridge is just that – a long and tunnel-like bridge – as the canal approaches its end in the town of Sowerby Bridge. But it’s kept one of the most spectacular pieces of engineering from the canal restoration till last…

The deepest lock

Part of the original route through the town (including two locks) having been filled in and a road diverted to run along it, a new route for the restored canal was needed. But there wasn’t really any space for one. The solution was to replace the two lost locks with one double-depth one (at 19ft 8in the deepest in the country), which exits directly into a new tunnel. This takes a sharp curve to the right, emerging on the far side of a main road and rejoining the original route.

A final two locks descend to reach a junction with the Calder & Hebble Navigation. Turn right to continue the route down the Calder Valley towards Wakefield, or left for a short dead-end to a terminal basin surrounded by restored historic waterway warehouses, and a splendid place to stop for a rest after your trans-Pennine cruise.